THE CHURCH QUIESCENT

DJ. Taylor wonders why we tolerate abuse

of Christianity, but not of any other religion

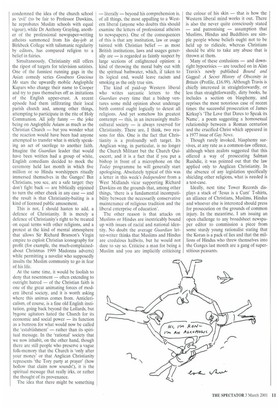

NOT many Spectator readers, I imagine, will have heard of a musical ensemble called Cradle of Filth. Their exploits are generally recorded only in specialist publications such as Kerrang!, and their records never trouble the charts. Nevertheless, in their modest way, they offer a neat little parable for a great deal of hypocritical modern thinking about religion.

Cradle of Filth are exponents of a brand of music known as 'death metal' or 'black metal' — loud, fast and. unlike other kinds of loud, fast music, openly Satanist. Here, perhaps, some socio-musical context is in order. In Scandinavia, 'black metal' is a highly sinister phenomenon that has produced church-burnings and, on more than one occasion. murder (a Norwegian musician named Varg Vikernes is serving a life sentence for slaughtering an ex-bandmate). The UK variant, on the other hand, tends to the mildly comic-book, and expresses itself in inflammatory T-shirts and rogueish promotional videos on which bare-breasted lovelies wallow in vats of fake blood.

Among other items of merchandise, Cradle of Filth have produced an eye-catching T-shirt stamped with the slogan 'Jesus is a Cunt' and featuring a picture of a nun masturbating with a crucifix. It is with a bundle of these garments, reposing on the shelf of the Glasgow branch of Tower Records, that our story begins.

Alerted by the Lord Provost of the city, who had received several complaints, police entered the Argyll Street premises earlier this year and ordered the apparel to be removed. At a subsequent press conference. the Lord Provost disclosed that he had written to the company expressing his 'disgust' and to underline that material like this must never be put on sale again'. Queerly, within a week the T-shirts were back in the shop. 'We pride ourselves on offering the largest range of products available,' Tower Records's managing director explained, 'and leaving it to the customers to choose whether they wish to purchase them.'

Now, free speech — and presumably the liberty to sell 'Jesus is a Cunt' T-shirts falls into this category — is a wonderful thing. All the same, Tower Records's defence of its marketing policy raises some interesting questions. Let us say, for example, that I were to sit down and manufacture a couple of dozen T-shirts emblazoned with the message 'Mohammed is a Motherfucker' or — swinging the spiritual compass a bit further — 'Vishnu is a Wanker'. Would Tower Records feel like stocking them? The answer, one imagines, is no, and the reason would be as much practical as ideological, if only because a band of outraged imams and their followers would be capable of causing a much bigger stink in the streets of Glasgow than the Lord Provost.

Curiously, this stand-off between shocked city fathers and a right-on retailing giant was set in context by the religious service staged to commemorate World Holocaust Day in late January. No television viewer who watched the proceedings for a moment could have failed to note that the rather dusty Anglicanism that generally surfaces in official ceremonies was out, and that it had been replaced by a fanatical inclusiveness. As Catholic priests rubbed shoulders with archimanthites, while Hindu votaries brought up the rear, the subliminal — and government-fostered — message was abundantly clear.

Although we inhabit a notionally Christian country — which is to say that a Christian ethical and administrative framework still stretches above the rising secularist tide — a comprehensive religious tolerance is enjoined. By the same token, any outrage done to religious sensitivities is routinely deplored. But to assume that all religious beliefs are of equal validity in early 21stcentury Britain would be a mistake. If one wanted a convenient summary of the attitude towards religious belief shown by the majority of the broadsheet newspapers and upper-brow television producers, it would be this: all religions are equal, but some are less equal than others. And Anglican Christianity is the least equal of all.

Evidence of this prejudice is apparent throughout modern medialand. On the most basic level, it is manifested in the broadcasting media's constant reluctance to fulfil its statutory obligations in the field of religious programming. An estimated 7 per cent of the UK's population regularly attends places of Christian worship — more than the aggregate attendance at Premiership and Nationwide League football matches each Saturday afternoon — and yet the BBC's nods in the direction of its Christian audience are generally limited to Songs of Praise and a few late-night Evoyman specials. Without watchdog vigilance, it is probably accurate to say that the television channels would give up on their 'God slots' altogether. In the meantime, underfunded, marginalised and screened at odd hours, religious programming narrowly survives, never quite managing to throw off its status as a faintly embarrassing anachronism. But this more or less benign neglect is markedly different from the outright antagonism on display elsewhere in the media.

One of the most regular sights in the comment pages of the Independent and the Guardian is a denunciation of Christian belief, sparked off by some episcopal pronouncement or Synod vote, and couched in tones of near-hysteria. I was particularly taken by a piece by the Independent's Mark Steel shortly before Christmas in which he compared the infant Jesus, recumbent in his cradle, to a chimpanzee. Over the past week, this note has been repeatedly struck in the controversy surrounding David Blunkett's plans to extend the number of church schools. Professor Richard Dawkins has condemned the idea of the church school as 'evil' (to be fair to Professor Dawkins, he reprobates Muslim schools with equal vigour), while Dr Anthony Grayling, another of the professional newspaper-writing atheists summoned from his day-job at Birkbeck College with talismanic regularity by editors, has compared religion to a belief in fairies.

Simultaneously, Christianity still offers the ripest of targets for television satirists. One of the funniest running gags in the Asian comedy series Goodness Gracious Me stars the upwardly mobile Anglophile Kupars who change their name to Cooper and try to pass themselves off as imitations of the English upper-crust. A recent episode had them infiltrating their local parish church and, among other things, attempting to participate in the rite of Holy Communion. All jolly funny — the joke being on Anglophile Asians as much as the Christian Church — but you wonder what the reaction would have been had anyone attempted to transfer what is strictly speaking an act of sacrilege to another faith. Imagine the Guardian leader that would have been written had a group of white, English comedians decided to mock the ceremony held last month in which five million or so Hindu worshippers ritually immersed themselves in the Ganges! But Christians, you see, are a safe target: they don't fight back — are biblically enjoined to turn the other cheek in any case — and the result is that Christianity-baiting is a kind of licensed public amusement.

This is not, I should hasten to add, a defence of Christianity. It is merely a defence of Christianity's right to be treated on equal terms with other religions, and a protest at the kind of mental atmosphere that allows Sir Richard Branson's Virgin empire to exploit Christian iconography for profit (for example, the much-complainedabout Christmas 1999 Madonna adverts) while permitting a novelist who supposedly insults the Muslim community to go in fear of his life.

At the same time, it would be foolish to deny that resentment — often extending to outright hatred — of the Christian faith is one of the great animating forces of modern liberal society, and it is worth asking where this animus comes from. Anticlericalism, of course, is a fine old English institution, going back beyond the Lollards, but bygone agitators hated the Church for its economic and social power — its function as a buttress for what would now be called the 'establishment' — rather than its spiritual message. In the 'rational' society that we now inhabit, on the other hand, though there are still people who preserve a vague folk-memory that the Church is 'only after your money' or that Anglican Christianity represents 'the Tory party at prayer' (how hollow that claim now sounds!), it is the spiritual message that really irks, or rather the thought of its provenance.

The idea that there might be something — literally — beyond his comprehension is, of all things, the most appalling to a Western liberal (anyone who doubts this should examine the letters of professional atheists to newspapers). One of the consequences of this is that any institution, law or usage tainted with Christian belief — as most British institutions, laws and usages generally are — is regarded as faintly suspect by large sections of enlightened opinion: a kind of throwing the moral baby out with the spiritual bathwater, which, if taken to its logical end, would leave racism and smoking as the only true sins.

The kind of paid-up Western liberal who writes sarcastic letters to the Guardian every time that a bishop ventures some mild opinion about underage birth control ought logically to detest all religions. And yet somehow his greatest contempt — this, in an increasingly multicultural society — is always reserved for Christianity. There are, I think, two reasons for this. One is the fact that Christianity is a profoundly soft target. Its Anglican wing, in particular, is no longer the Church Militant but the Church Quiescent, and it is a fact that if you put a bishop in front of a microphone on the Today programme he will generally start apologising. Absolutely typical of this was a letter in this week's Independent from a West Midlands vicar supporting Richard Dawkins on the grounds that, among other things, 'there is a fundamental incompatibility between the necessarily conservative maintenance of religious tradition and the liberal enterprise of education'.

The other reason is that attacks on Muslims or Hindus are inextricably bound up with issues of racial and national identity. No doubt the average Guardian letter-writer thinks that Muslims and Hindus are credulous halfwits, but he would not dare to say so. Criticise a man for being a Muslim and you are implicitly criticising

the colour of his skin — that is how the Western liberal mind works it out. There is also the never quite consciously stated — and patronising — assumption that Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists are simple people whose beliefs ought not to be held up to ridicule, whereas Christians should be able to take any abuse that is thrown at them.

Many of these confusions — and downright hypocrisies — are touched on in Alan Travis's newly published Bound and Gagged: A Secret History of Obscenity in Britain (Profile, £16.99). Although Travis is chiefly interested in straightforwardly, or less than straightforwardly, dirty books, he includes a section on blasphemy, and reprises the most notorious case of recent times: the successful prosecution of James Kirkup's 'The Love that Dares to Speak its Name', a poem suggesting a homosexual relationship between a Roman centurion and the crucified Christ which appeared in a 1977 issue of Gay News.

Though rarely invoked, blasphemy survives, at any rate as a common-law offence, although when zealots suggested that this offered a way of prosecuting Salman Rushdie, it was pointed out that the law applied only to Anglican Christianity. In the absence of any legislation specifically shielding other religions, what is needed is a test-case.

Ideally, next time Tower Records displays a stack of 'Jesus is a Cunt' T-shirts, an alliance of Christians, Muslims, Hindus and whoever else is interested should press for prosecution on the grounds of common injury. In the meantime, I am issuing an open challenge to any broadsheet newspaper editor to commission a piece from some sturdy young rationalist stating that the Koran is a pack of lies and that the millions of Hindus who threw themselves into the Ganges last month are a gang of superstitious peasants.

Previous page

Previous page