Chess

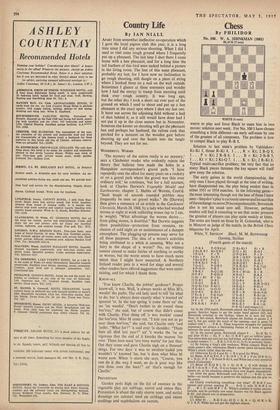

By PHILIDOR No. 100. W. A. SHINKMAN (1881) BLACK (5 men) WHITE (6 men) WHITE to play and force Black- to mate him in two moves: solution next week. For No. 100 I have chosen something a little different—an early self-mate by one of the greatest of all composers. The problem is how to compel Black to play R–R 8.

Solution to last week's problem by Vakhlakov: Kt–Kt 5, threat R–Kt 8. 1 . . , R x Kt; 2 B–Q 8. 1 . . . P x Kt; 2 R–B 6. 1 . . . B x Kt; 2- B–B 5. 1 . .. Kt x Kt; 2 Kt–Q 7. 1 ...K x Kt;. 2 R–Kt 8. Typical multi-sacrifice problem; the very fact that so many Black pieces threaten the key square will itself give away the solution.

The early games in the world championship, the only ones I have played through at the time of writing, have disappointed me, the play being weaker than in either 1951 or 1954 matches. In the following game— the most interesting though not the best of those I have seen—Smyslov's play is curiously uneven and his sacrifice of the exchange on move 29 incomprehensible; Botwinnik also is not his usual sure self. However, perhaps readers will find it consoling to see that under pressure the greatest of players can play quite weakly at times. The notes are based on those by H. Golombek, who is in Moscow as judge of the match, in the British Chess Magazine for April.

White, V. SMYSLOV Black, M. M. BOTWINNIK Opening, Sicilian

(Fourth game of the match)

1 P-K 4 P-Q B 4 (a) 21 Kt-Kt 3 Kt x B .2 Kt-K B 3 Kt-Q B 3 22 Q x Kt B-Q 3 3 P-Q 4 P x P 23 P-Q B 4 P x P s

4 Kt x P Kt-B3 24B x QBP Q-Kt 3 5 Kt-Q B 3 P-Q 3 25 Q-K 2 (f) K-R 2

6 B-K Kt 5 P-K 3 26 R-Q B 1 B-Kt 2 7 Q-Q 2 P-Q R 3 27 K R-Q 1 P-K 5 (g)

8 0-0-0 P-R 3 28 B-Q 5 13:-B 5 9 B-K 3 B-Q 2 (b) 29 B x B? (h) B x R 10 P-B 3 P-Q Kt 4 30 B-Q 5 B-K 6

11 Kt x Kt B x Kt 31 P x P PXP

12 Q-B 2 Q-B 2 32Q-B4 R-R 2 13 B-Q 3 13-1C 2 33Q x P R (R 2)-0 2

14 Q- Kt 3 (c) P-Kt 3 34 R-Q 3 B- Kt 4 15 K-Kt 1 0-0-0 35 Q-B 3 R x B (I) 16 Q-B 2 K-Kt 2 36 R x R Q-Kt 8 ch 17 Kt-K 2 P-K 4 (d) 37 K-B 2 R-11 1 ch 18 Kt-B 1 (e) P-Q 4 38 K-Q 3 Q-Kt 8 ch

19 P x P Kt x P 39 K-Q 4 Q x P ch 20 K R-K 1 P-B 4 40 K-K 4 R-K I ch

41 K-Q 3 and resigns (J) (a) In the 1954 snatch, Botwinnik played the French in the early games; Smyslov began to get the upper hand against this, and Botwinnik switched to the Sicilian, where he in turn did well. Now in this match, Botwinnik played the Sicilian in games 2, 4 and 8, but got rather the worst of the opening—and in game 10 replied with I . . . P-K 4. These long-term struggles for opening supremacy are always a fascinating feature of a series of games between the same opponents.

(b) In the second game, Botwinnik played 9 . , . Kt-K Kt 5; and after 10 Kt x Kt, P x Kt; II B-B 5 got an inferior game. Text move does not turn out too well either, and the whole variation is rather suspect; 7 .. B-K 2; 8 0-0-0, 0-0; is probably better.

(c) By forcing a king's side weakness, White compels Black to castle queen's side, whereupon Black's earlier pawn advances help White's attack rather than his own.

(d) Otherwise Kt-Q 4 and Kt x B is good for White. (e) Better 18 P-Q B 4!, P x P; 19 B x P, B x P ch; 20 B-Q 3!, B x B ch; 21 R x B threat B-Kt 6, and White has a very powerful attack (Golombek). (f) Better 25 R-Q B 1, Q x Q; 26 R x Q with threats of Kt-R 5 ch or B x P ch. It is no longer in White's interest to keep queens on, as his attacking chances have now largely disappeared. (g) After the game, Botwinnik said that 27 . . . B-Kt 1; was better—no doubt because it preserves the bishops and the grip on the centre.

(h) Clearly overlooking something—but what? 29 R-B 5 was natural and correct meeting 29 . . . B-Q 3; with 30 R-B 2 or

29 . B x P; with 30 P x P. White's position is rather uncom- fortable, and he probably saw some illusory win for Black against R-B5 and played text in desperation.

(i) Decisive.

(.1) After 41. R-K 6 ch; 42 Q x R, B X Q; 43 K x B, Q x R P; White:has not got the slightest chance.

Previous page

Previous page