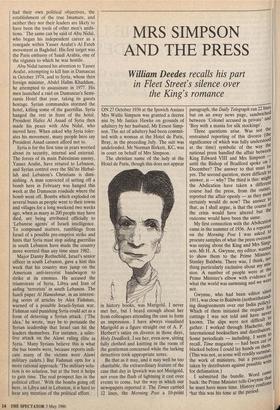

MRS SIMPSON AND THE PRESS

in Fleet Street's silence over the King's romance

ON 27 October 1936 at the Ipswich Assizes Mrs Wallis Simpson was granted a decree nisi by Mr Justice Hawke on grounds of adultery by her husband, Mr Ernest Simp- son. The act of adultery had been commit- ted with a woman at the Hotel de Paris, Bray, in the preceding July. The suit was undefended. Mr Norman Birkett, KC, was in court on behalf of Mrs Simpson.

The christian name of the lady at the Hotel de Paris, though this does not appear

in history books, was Marigold. I never met her, but I heard enough about her from colleagues attending the case to form an impression. I have always visualised Marigold as a figure straight out of A. P. Herbert's satire on divorce in those days, Holy Deadlock. I see her, even now, sitting fully clothed and knitting in the room of the gentleman concerned while the lurking detectives took appropriate notes.

Be that as it may, and it may well be too charitable, the extraordinary feature of the case that day in Ipswich was not Marigold, nor even the flash of lightning it cast over events to come, but the way in which our newspapers reported it. The Times carried 12 lines, the Morning Post a 10-point paragraph, the Daily Telegraph ran 22 lines but on an away news page, sandwiched between 'Colonel accused in private' and 'Boy with a mania for silk stockings'. Three questions arise. Was not the restrained reporting of this divorce (the significance of which was fully understood at the time) symbolic of the way the national press handled the affair between King Edward VIII and Mrs Simpson — until the Bishop of Bradford spoke on 1 December? The answer to that must be yes. The second question, more difficult to answer, is — why? The third is this: might the Abdication have taken a different course had the press, from the outset, reported the affair openly — as they most certainly would do now? The answer to that, as I shall argue, is that the course of the crisis would have altered but the outcome would have been the same. My first connection with the Abdication came in the summer of 1936. As a reporter on the Morning Post I was asked te procure samples of what the press overseas was saying about the King and Mrs Sine son. Mr H. A. Gwynne, my editor, wanted to show them to the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin. There was, I think, nO" thing particularly exclusive about my Mts. sion. A number of people were at the Prime Minister's elbow with evidence et what the world was surmising and we were not. Gwynne, who had been editor since 1911, was close to Baldwin (nothwithstand- ing disagreements over our India policy). Which of them initiated the request for cuttings I was not told and have never known. The slips were not difficult t0 gather. I worked through Hachette, the international booksellers and distributors. Some periodicals — including, I seem t° r recall, Time magazine — had been cut o blacked before I could lay hands on their. (This was not, as some will readily suninisei; the work of ministers, but a precaurict taken by distributors against possible writ' for defamation.)

_

I submitted the bundle. Word can' back: the Prime Minister tells Gvvynne that he must have more time. History confirros +hat this was his tone at the period. I became so impressed by the extraor- dinary situation, in which all the world knew about the King's affair except ourselves, that I tried a hand of my own. In September, with the help of a colleague, I drafted some words for the Morning Post to publish. Gwynne politely acknowledged this but said that, on learning of the Possibility of the Morning Post's entering even a subdued opinion, the Prime Minis- ter had pleaded again, and successfully, for more time. We killed the draft.

Within a month of this, my marginal connection with King Edward's affair took a different turn. On 18 and 19 November the King paid a visit to South Wales. I did not cover the tour but I heard about it, Partly from journalists who went, partly from an uncle, Sir Wyndham Deedes, in Whose house I resided. He was working with Lionel Ellis at the National Council of Social Service. Ellis was one of the party with the King. It was brought home to me how much the King was under strain. On 18 November the King visited Merthyr Tydfil and the derelict steel plant nearby at Dowlais which had put most of the local community out of work. What he actually said was this: 'These steel works brought the men here. Something must be done to see that they stay here — working.' The words which echoed like a thunderclap Yound the kingdom and over the heads of hapless ministers were: 'Something must be done!'

Absurdly, those words were later brought into the Abdication crisis. Minis- ters, resentful of this royal reproach (so it was said), determined that the King must go.

For me they had another consequence. 'Something must be done.' Very well then, let us make a contribution, however mod- est. The Morning Post resolved that every Child of unemployed parents throughout the so-called Distressed Areas (South wales, north-west Cumberland and the „, '11)01'01-East) should receive on Christmas ay by post and anonymously a gift worth 2s 6d (today about £2.50). I was told to get on with it. Poignantly, the King contrived to in himself in this small endeavour. He Sent through Alec Hardinge what must have been one of the last cheques of his reign. Though long forgotten, the fund carried one of the King's last imprints. A Year later, and again in 1938, Lord Cam- rose asked me to carry on the idea for the Telegraph after he had acquired the morning Post. Most of the royal family souffbscribed and Queen Mary came to the ice to cheer us on. I felt I understood Why.

an But this is some way removed from 'e ,..swering that second difficult question: B lrni Y. Was this affair kept so dark by the actish press until Dr A. W. F. Blunt, mishop of Bradford, delivered his by no ma of sensational reflections of Tuesday, 1 December? For those unfamiliar with them, the gist of lay in three sentences: `. . improper for me to say anything except to commend him, and to ask you to commend him, to God's grace, which he will so abundantly need. . . if he is to fulfil his duty faithfully. We hope that he is aware of his need. Some us wish that he gave more positive signs of such aware- ness.' The Daily Telegraph gave the story half a column on a subsidiary news page. Other newspapers were more generous The cat was out of the bag.

There were at least two events during the summer which might have had the same effect. The lesser event was on 27 May, when the Court Circular showed that among royal guests for a dinner party were Mr and Mrs Ernest Simpson. The second occurred in August, when the King took a holiday cruise in the Mediterranean in the yacht Nahlin. Pictures of the King (in shorts only) and of Mrs Simpson (in a bathing dress) circulated freely. They in- creased speculation, but press comment in Britain remained muted.

Dr Blunt's speech on 1 December was therefore the culmination of several epi- sodes, any one of which might have brought matters to a head — and most certainly would have done so today. Was there a conspiracy of silence among the press lords? The prima facie evidence suggests that there must have been. My own experience of those times persuades me that there was not. For one thing, the press leaders did not get on very well with each other. Lords Beaverbrook and Rothermere hunted together. Neither Lord Camrose of the Daily Telegraph nor H. A. Gwynne of the Morning Post was likely to enter into arrangements with them. Nor was Geoffrey Dawson of the Times.

Like Gwynne, Dawson saw the Prime Minister fairly regularly. But he did not consort with other editors. Indeed, the Times historians, Oliver Woods and James Bishop, make this point about Dawson: 'But in other respects he was out of touch. He appears to have been in ignorance of the activities at the time of the King and Lord Beaverbrook, directed at muzzling the popular press.' (The Story of The Times, Michael Joseph, 1983.) Now it is undeniable that the King was troubled by what the press might say and through his own limited channels — mainly Beaver- brook and Sir Walter Monckton, KC — sought to influence this, but it was not a very formidable obstacle.

Woods and Bishop say that Dawson saw Gwynne on the morning of 16 November.

Gwynne (they say), seeking guidance, wanted simultaneous publication by all the newspapers at government discretion. Dawson's diary adds: 'The main point to me was that the Morning Post was not going to do anything without a lead.' That does not altogether square with my im- pression, which was that Gwynne was taking his pace from Baldwin, not from his colleagues on other newspapers; but Daw- son kept a diary and I did not.

The only consultation between senior figures in Fleet Street which I know of came on the day that Bishop Blunt spoke. Lord Camrose of the Daily Telegraph, Gwynne of the Morning Post and Dawson of the Times consulted and agreed that editorial comment on the speech should be deferred until the following day. They reckoned, rightly, that Beaverbrook and Rothermere would be taking the same course.

This really does not add up to a conspira- cy to suppress news about the affair. We have to look deeper for an explanation of the long silence of that summer and au- tumn. A passage in the Times account is suggestive: The Crown in England touches atavistic, often subsconscious, springs of human emo- tion. The leaders of opinion, when they saw the Crown threatened, spontaneously coalesced to contain the explosion and en- sure that it did as little damage as possible.

Too grandiloquent? I am not so sure. The factor we have to enter, and the hardest one now to accept, is how much our society has changed between that year and this; how dramatically the style of our news media has changed. Our attitudes to au- thority have changed. Our view of majesty has changed. Our beliefs have changed. No call to moralise about it. But it is so.

Lord Hartwell has reminded me of a feature which appeared at about this time in an American newspaper. It carried five portraits: Mrs Simpson's two previous hus- bands, the King, the Archbishop of Can- terbury and the Prime Minister. The cap- tion ran: 'First mate, second mate, third mate, Primate, Checkmate.' Such a feature in any of our own newspapers in 1936 was unthinkable. It is not unthinkable in these enlightened times.

So, finally, had we been then what we have become, had we in newspapers been ready to do what we unhesitatingly would do now, might the outcome have been different? I think not.

For it was not, as some later historians would have us think, determined by the 'Establishment' — a Prime Minister, an Archbishop, the Dominions, or even by readers of the Morning Post. At one critical point after the crisis had broken, Stanley Baldwin faced a difficult meeting of his own party in private. Members were divided. He made one of his appeals. He told them to forgo some of their weekend engagements, to get into the pubs and working men's clubs and to talk to people. They would meet again on Monday. When they met, the message was clear. So it came about. In any case, the King's mind was made up. Our progressive, impulsive, intrusive, intensive media of today would have changed the timing, not his decision. On the Friday night on which it ended, I had a private engagement, a dance for my eldest sister's coming of age at a hotel in Folkestone. During the afternoon a trusted source called me to say that in all likeli- hood the King would be leaving the coun- try that night in an aircraft from Lympne airport. Lympne was adjacent to Port Lympne, home of Sir Philip Sassoon, a long-standing friend of the King. It sound- ed possible.

I reached a compromise with my news- paper. Lympne was about ten miles from Folkestone. They would supply a car. During the evening, dressed in a white tie, I would keep an eye on the airport. I made three journeys there. On the third visit, for some mysterious reason, all the lights were ablaze. It was a mirage. The navy was looking after the King. While the dance was on, we stood on the floor to hear the final broadcast. 'At long last, I can say a few words of my own. . • • As dancing was resumed, I took the floor with a girl I liked and who had stood beside me during the broadcast. During our dance neither of us could think of a word to say to each other.

This article was specially written for a book" 1936, as recorded by The Spectator, intro- duced and edited by Charles Moore and Christopher Hawtree, to be published by Michael Joseph on 2 June (114.95).

Previous page

Previous page