Exhibitions

The Glory of Byzantium (Metropolitan Museum, New York, till 6 July)

The power and the glory

Martin Gayford

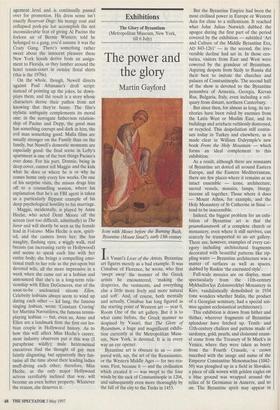

Icon with Moses before the Burning Bush, Byzantine (Mount Sinai?), early 13th century In Vasari's Lives of the Artists, Byzantine art figures merely as a bad example. It was Cimabue of Florence, he wrote, who first `swept away' the manner of the Greek artists he encountered, 'making the draperies, the vestments, and everything else a little more lively and more natural and soft'. And, of course, both mentally and actually, Cimabue has long figured as the starting point of Western art — year 0, Room One of the art gallery. But it is to what came before, the Greek manner so despised by Vasari, that The Glory of Byzantium, a huge and magnificent exhibi- tion currently at the Metropolitan Muse- um, New York, is devoted. It is in every way an eye opener.

Byzantine art is obscure to us — com- pared with, say, the art of the Renaissance, or the Western Middle Ages — for two rea- sons. First, because it — and the civilisation which created it — was swept to the four winds by the sack of Constantinople in 1204, and subsequently even more thoroughly by the fall of the city to the Turks in 1453. But the Byzantine Empire had been the most civilised power in Europe or Western Asia for close to a millennium. It reached what John Julius Norwich dubbed the apogee during the first part of the period covered by the exhibition — subtitled 'Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, AD 843-1261' — in the second, the irre- versible decline had set in. In those cen- turies, visitors from East and West were cowered by the grandeur of Byzantium. Aspiring despots from Sicily to Russia did their best to imitate the churches and palaces of Constantinople. The second half of the show is devoted to the Byzantine penumbra of Armenia, Georgia, Kievan Rus, Bulgaria, Italy, even including a reli- quary from distant, northern Canterbury.

But since then, for almost as long, its ter- ritories have been ruled by enemies from the Latin West or Muslim East, and its buildings and artefacts ruthlessly destroyed, or recycled. This despoliation still contin- ues today in Turkey and elsewhere, as is made clear in William Dalrymple's new book From the Holy Mountain — which forms an ideal complement to this exhibition.

As a result, although there are remnants of Byzantine art dotted all around Eastern Europe, and the Eastern Mediterranean, there are few places where it remains as an intact ensemble — icons, architecture, sacred vessels, mosaics, lamps, liturgy, incense all together. Those where it does — Mount Athos, for example, and the Holy Monastery of St Catherine in Sinai tend to be inaccessible.

Indeed, the biggest problem for an exhi- bition of Byzantine art is that the gesamtkunstwerk of a complete church or monastery, even where it still survives, can scarcely be transported to an art gallery. There are, however, examples of every cat- egory including architectural fragments decorated with beautiful patterns like rip- pling water — Byzantine architecture was a matter of surfaces as well as spaces, dubbed by Ruskin 'the encrusted style'.

Full-scale mosaics are on display, most spectacularly from the 11th-century Mykhailivs'kyi Zolotoverkhyi Monastery in Kiev, vandalistically demolished in 1934 (one wonders whether Stalin, the product of a Georgian seminary, had a special ani- mus against ecclesiastical architecture).

This exhibition is drawn from hither and thither, wherever fragments of Byzantine splendour have fetched up. Tenth- and 11th-century chalices and pattens made of sardonyx, gold, pearls, and cloisonné enam- el come from the Treasury of St Mark's in Venice, where they were taken as booty from the Fourth Crusade, a crown inscribed with the image and name of the Emperor Constantine Monomachus (1042- 50) was ploughed up in a field in Slovakia, a piece of silk woven with golden eagles on a blue ground was wrapped around the relics of St Germanus in Auxerre, and so on. The Byzantine spirit may appear in even the tiniest object. The tip of a sceptre smaller than a thimble is patterned in the same way as the marble floor of a cathe- dral, though one would have to use a mag- nifying glass to see it in its full intricacy.

New York, where so much flotsam and jetsam has fetched up, including many descendants of Byzantine citizens, is not such an unlikely spot as one might suppose for this reconstruction of Byzantium. And this is an extraordinarily complete survey. Quite possibly the room at the Met which brings together that silk, crown and various other costly and precious objects offers the best opportunity since 1204 to reconstruct the luxurious surroundings of a Byzantine emperor of the 11th or 12th cen- turies — a secular world that has vanished much more completely than the religious one.

The second reason why Byzantine art can seem remote is that it operates on different principles to the art that followed Cimabue. From Giotto to Cezanne, West- ern art was, by and large, concerned with exploration of space, and mastery of natu- ralism. To step back beyond Cimabue is to step through the looking-glass into a world where everything is reversed. And Byzan- tine icons are not intended to represent solid figures in a threo-dimensional world. If one looks at them with that expectation, they may seem stereotyped and stiff, as they did to Vasari, the product of artists who 'had taught one to the other for many and many a year, without ever thinking of bettering their draughtsmanship'.

In fact, they are representations of holy beings, occupying spiritual, not natural, space. There is no recession, no air circu- lating around them, the saints, Christ and Madonna are just there — like a thought or a vision — against a background of bur- nished gold. That sheen, and the reflective- ness of other rich materials — the sparkle of jewels, the translucency of enamel, the glitter of mosaic — are a crucial part of the intended effect. Richly shimmering light is a metaphor for spirituality, for disembodi- ment.

Thus, in a stunning series of 12th-century icons from Sinai, the halos are burnished and scored into the flat gold so that they catch the light like those golden discs pre- sented to pop stars. In an icon of the annunciation, one of the most splendid of these, the Holy Ghost flutters down on a ray of light produced by the same means, so that it is visible only from certain angles. On the breast of Mary, the infant Christ is only just visible in outline. It is hard to think of a more poetic way of representing the immaterial.

These icons — seldom if ever seen in the West — give the lie to the Vasarian view of art history. Clearly, the finest Byzantine artists were not just the predecessors, but also the equals, of Cimabue and Duccio. The glory, and also the power, of Byzantine art have seldom been made so evident as they are at present at the Met.

Previous page

Previous page