A wheelbarrow full of surprises

Byron Rogers

A KIND OF JOURNAL by P. J. Kavanagh Carcanet, I:14.95, pp. 243, ISBN 1857546326

his book doesn't half keep you guessing. Most of the time the atmosphere is that of the scholarly quiet at the start of one of M. R. James's stories, that is before the thing with the face like crumpled linen comes. Somewhere on the Welsh Border a man who seems not to get out much, and spends most of his time alone, remembers books he has read and writers he has known. He is in no hurry, and there is the feel of autumn afternoons in some booklined room where you can almost smell the pipe smoke and the polish on the oak. Once you adapt to the pace you could read on and on.

Except that the essay you thought was about Cardinal Newman becomes one on George Moore, and George Onvell's journalism turns into Aberystwyth: it is like following the White Rabbit through the stack. Then there is the odd bewildering biographical detail as when Mr Kavanagh vaults over the bookshelves and, amidst Nazi regalia, is in the maddest episode of Father Ted I ever watched. His has to be the strangest life, as man of letters and actor, and the fact that he has been able to live it in our times is nothing short of miraculous.

He mentions writers that the editors who commissioned these collected columns have probably never read, perhaps never heard of: Gogarty and Lascelles Abercrombie, James Stephens, Austin Clarke, AE and Ivor Gurney, and it is a march past of ghosts out of old anthologies. Who reads AE now, all those milk-production figures and fairies? Who gives a toss that the Yeats of the 'Lake Isle' never heard an evening full of linnet's wings, or saw a linnet come to that? Well, one man does, and it is a matter for rejoicing that for 20 years he has been allowed to write about them, like a Welsh bard singing the old metres in the manor of some new hard-nosed Norman Marcher, kept on because it was obscurely felt he added some kind of tone. He is a good man, P. J. Kavanagh.

Listen to the things he quotes. This is John Cowper Powys, having seen some polar bears in a zoo:

One was tenderly scratching its hurt paw. It was lame. It scratched absent-mindedly like one puzzled, pondering on past and future, faintly recalling some arctic moss that was the cure.

This is the Yeats of Autobiographies, in prose startled out of booming genius into humour, and writing about William Morris 'saying to the only unconverted man at a socialist picnic, "I was brought up a gentleman and now as you can see can associate with all sorts," '

And this is Yeats himself, probing the 'ancient mysteries':

If you burnt a flower to ashes and put the ashes under, I think, the receiver of an air pump, and stood the receiver for so many nights, the ghost of the flower would appear hovering over the ashes. I got together a committee which performed this experiment without results.

The man who wrote that was either a crackpot or a consummate comedian.

The next minute Kavanagh is amongst his political shelves, quoting the reminiscences of a prisoner who awaited execution under Stalin (he was able to share these because he got off). Apparently you knew you were going to get shot if you were told to leave your belongings, though I read somewhere that you knew when because that morning, man or woman, you were issued with clean underwear. Pure style.

But I like it when Kavanagh gets out, when for instance he attends a reunion dinner at his old Oxford college. The dialogue is spot on in this one short paragraph, as anyone who has attended such events will recognise:

We seemed automatically to regress into undergraduate self-deprecation and pretencegloom: 'Hello, Richard, what are you up to these days?' 'Law (pronounced with melancholy, as though this were the dreariest of servitudes). 'Actually, the bugger's a judge.' 'You a judger 'Yen'

The `yer' is perfect.

I liked even more this splendid denunciation, in which Kavanagh enters the rhythmic hwyl of a Welsh preacher:

I have seen rows of empty beer cans swept off tables by beer-bellies on the cross-channel ferry. I have seen ancient hedges grubbed up to the sound of Radio One. 1 have heard teachers deplore the ignorance of their pupils yet fiercely defend the ways they teach. I have heard students declare that rhythm in poetry (and prose) is irrelevant. I have endured muzak in old public houses. All these things I have seen and heard, and more, but I never despaired of England until, like a Orin through the floorboards, Harry Carpenter appeared on the dais at the presentation ceremony after the Open Championship of Golf.

It does not matter what the wretched Harry did. He is doomed to all eternity in that dying fall.

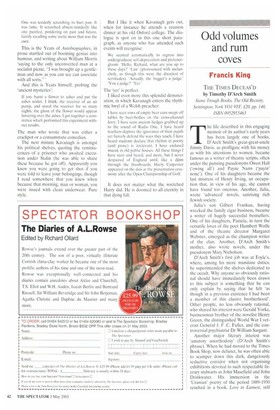

Previous page

Previous page