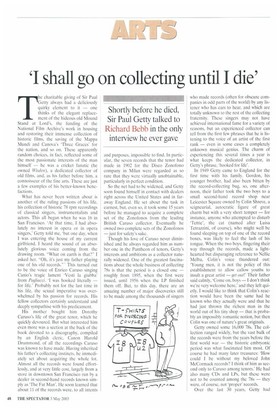

shall go on collecting until I die'

Shortly before he died, Sir Paul Getty talked to Richard Bebb in the only interview he ever gave The charitable giving of Sir Paul Getty always had a deliciously quirky element to it — one thinks of the elegant replacement of the hideous old Mound Stand at Lord's, the funding of the National Film Archive's work in housing and restoring their immense collection of historic films, the saving of the Mappa Mundi and Canova's 'Three Graces' for the nation, and so on. These apparently random choices, in fact, reflected some of the most passionate interests of the man himself — he was a cricket fanatic (he owned Wisden), a dedicated collector of old films. and, as his father before him, a connoisseur of the fine arts. These are just a few examples of his better-known benefactions.

What has never been written about is another of the ruling passions of his life, his collection of historic 78 rpm recordings of classical singers, instrumentalists and actors. This all began when he was 16 in San Francisco. 'At that time. I had absolutely no interest in opera or in opera singers,' Getty told me, 'but one day. when I was entering the house of my current girlfriend. I heard the sound of an absolutely glorious voice coming from the drawing room. "What on earth is that?" I asked her. "Oh, it's just my father playing one of his old records."' This turned out to be the voice of Enrico Caruso singing Canio's tragic lament 'Vesti la giubba' from Pagliacci. 'I was hooked literally — for life.' Probably not for the last time in his life, the sexual imperative was overwhelmed by his passion for records. His fellow collectors certainly understand and deeply sympathise with his predicament.

His mother bought him Dorothy Caruso's life of the great tenor, which he quickly devoured. But what interested him even more was a section at the back of the book devoted to a discography, compiled by an English cleric, Canon Harold Drummond, of all the recordings Caruso was known to have made. Having inherited his father's collecting instincts, he immediately set about acquiring the whole lot. Almost all the records were found effortlessly, and at very little cost, largely from a store in downtown San Francisco run by a dealer in second-hand records known simply as 'The Fat Man'. He soon learned that about 11 of the records were, to all intents and purposes, impossible to find. In particular, the seven records that the tenor had made in 1902 for the Disco Zonofono company in Milan were regarded as so rare that they were virtually unobtainable, particularly in perfect condition.

So the net had to be widened, and Getty soon found himself in contact with dealers right across the United States and in faraway England. He set about the task in earnest, but. even so, it took some 15 years before he managed to acquire a complete set of the Zonofonos from the leading British Caruso collector. Eventually he owned two complete sets of the Zonofonos — just for safety's sake.

Though his love of Caruso never diminished and he always regarded him as number one in the Pantheon of tenors, Getty's interests and ambitions as a collector naturally widened. One of the greatest fascinations about the whole business of collecting 78s is that the period is a closed one — roughly from 1895, when the first were issued, until 1956 when the LP finished them off. But, to this day, there are an amazing number of major discoveries still to be made among the thousands of singers who made records (often for obscure companies in odd parts of the world) by any listener who has ears to hear, and which are totally unknown to the rest of the collecting fraternity. These singers may not have achieved international fame for a variety of reasons, but an experienced collector can tell from the first few phrases that he is listening to the voice of an artist of the first rank — even in some cases a completely unknown musical genius. The charm of experiencing this several times a year is what keeps the dedicated collector, in Getty's phrase, 'hooked for life'.

In 1949 Getty came to England for the first time with his family. Gordon, his younger brother, had also been bitten by the record-collecting bug, so, one afternoon, their father took the two boys to a small second-hand record shop near Leicester Square owned by Colin Shreve, a seigneurial, autocratic figure of great charm but with a very short temper — for instance, anyone who attempted to disturb `Tettie', the cat (named after Luisa Tetrazzini, of course), who might well be found sleeping on top of one of the record boxes, was likely to feel the lash of his tongue. When the two boys, fingering their way through the records, made a lighthearted but disparaging reference to Nellie Melba, Colin's voice thundered out: 'Young men, it is not the policy of this establishment to allow callow youths to insult a great artist —get out!' Their father said calmly, 'Come on. boys — I don't think we're very welcome here,' and they left quietly. I would like to think that Colin's reaction would have been the same had he known who they actually were and that he had just thrown the richest man in the world out of his tiny shop — that is probably an impossibly romantic notion, but then Colin was one of nature's great originals.

Getty owned some 16,000 78s. The collection ranged widely, but the vast bulk of the records were from the years before the first world war — the historic embryonic period was what fascinated him most. Of course he had many later treasures: 'How could I be without my beloved John McCormack records? I think of him as second only to Caruso among tenors.' He had also many CDs and LPs, but these were not to be counted among the 78s — they were, of course, not 'proper' records.

Over the last 30 years, Getty had acquired the best things from three major British collections, and these resulted in his owning the finest collection of discs from the historic period of recording in private hands. His only serious rival was the collection held by the University of Yale in New Haven, but, of course, that is a public institution. Nevertheless, the search to fill gaps in his holdings was avidly pursued until the end, largely from record dealers' auction lists. 'I shall go on collecting until the day that I die!' he declared.

The greatest ambition of Getty's life as a collector was to own all the records of Angelica Pandolfini, a highly regarded soprano whose principal claim to fame is that she created the title role in Cilea's opera Adriana Lecouvrear at the Teatro Lirico in Milan in November 1902. That same month, probably while the opera was still being sung at the Lirico, she and her fellow creators, Caruso and the great baritone Giuseppe De Luca, each made a record of one of their principal arias for the Gramophone and Typewriter Company (later to evolve into HMV and EMI). Naturally these records are of the greatest historic and musical interest (the Caruso and De Luca records are accompanied at the piano by the composer) but, though all three are very hard to find, the Pandolfini is not thought to exist in more than five or six copies in the entire world. The further four recordings that she made are even rarer, and one of them did not turn up as a playable copy until about two years ago.

Getty told me that he had recently been in touch with Sergio Alfonsi, a youngish Italian collector, who used to go without fail to the street market in Turin at about six o'clock in the morning every Sunday of the year. One weekend he found on a stall a couple of albums of old vocal 78s, and, on examining album number one, the first three records were by Mattia Battistini, Alessandro Bonci and Riccardo Stracciari (al] extremely famous singers in the early years of the last century but whose records sold in such vast quantities that they are comparatively easy to find even today). The fourth record, however, was a completely different matter and enough to cause an immediate cardiac arrest in any knowledgeable record collector — the 'L'altra notte' from Boito's Mefistofele sung by Angelica Pandolfini. Controlling his volcanic excitement as best he could so as not to alert the suspicions of the stallholder, and wondering if lightning might conceivably strike twice, he turned his attentions to album number two, carelessly leaving the first album unguarded.

To his absolute horror and dismay, out of the corner of his eye, he saw that a rival collector was now examining album number one which still had the Pandolfini in it. Even worse, he was in the process of pulling a record out of its tight sleeve. For a timeless moment he was sure that it was the Pandolfini that was being removed.

But it wasn't. The rival collector paid for his Battistini and quietly moved on. Alfonsi was left shaking from the aftermath of the terror of having almost bungled the greatest collecting opportunity of his life. Unfair to the poor dealer? Not at all. In the world of collecting antiques of any kind, shape or form, the truth is that knowledge is everything.

Getty already had three of the Pandolfini records in his collection, so the remaining two were major wants. He therefore offered the young collector his second set of the Caruso Zonofonos in exchange for the Pandolfini. but, very admirably, Alfonsi refused to part with it at any price.

Getty badly wanted to complete his set of the four records sung by the Scottish soprano Mary Garden, who created the role of Melisande in Pe!leas et Melisande, and which were all accompanied by Claude Debussy himself. He would not have dismissed lightly the chance to acquire the unique test pressings of the unpublished records from Tosca sung by its creator, Hariclea Darelee, which were seen to be in her possession at the Casa di Riposo in Milan in 1939, and which disappeared when she returned to Romania before the war started. At least one of the five records made by the great Meyrianne fleglon, with Camille Saint-Saens at the piano, would have been given a warm welcome.

But the ultimate prize — the Holy Grail of any vocal record collector — would have been the acquisition of the two unpublished test pressings that the legendary tenor Jean de Reszke is known to have made for the Fonotipia Company in Paris in 1904 or 1905. Tragically for posterity, he refused to allow them to be published and ordered the destruction of the matrices. The hope has always been that test pressings, which must have been made for de Reszke to reject them, might have survived, but at this late stage no sighting of them has ever been reported. So the art of one of the most admired singers and artists of all time seems to have vanished without trace from the earth. The stuff of dreams of any millionaire record collector were made from just such things.

Previous page

Previous page