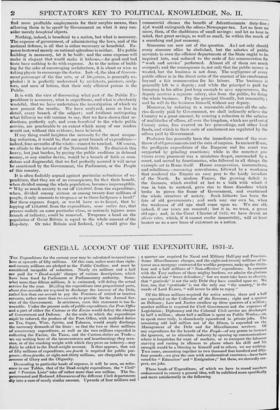

INTRODUCTION.

ECONOIdY is one of the chief duties of a State, as well as of an in- dividual. It is not only a great virtue in itself, but it is the pa- rent of many others. It preserves men and nations from the com- mission of crime and the endurance of misery. The man that lives within his income, can be just, humane, charitable, and inde- pendent. He who lives beyond it becomes, almost necessarily, rapacious, selfish, mean, faithless, contemptible. The economist is easy and comfortable; the prodigal harassed with debts, and unable to obtain the necessary means of life. So is it with na- tions. National character, as well as national happiness, has, from the beginning of the world to the present day, been sacrificed on the altar of profusion. The duty of Economy is not more important than difficult. The Government of every State lies under a constant temptation to transgress it ; and this temptation exists under every form of government that human ingenuity has yet devised. History shows that it has been yielded to in republics as well as mo- narchies ; and the only republic that can be fairly instanced as an exception, has hardly lived long enough to enable us to ascertain whether its constitution contains an antidote against the lurking poison. Had the United States of America been established some centuries ago, the original simplicity of their institutions would probably not have protected them from the encroachments of am- bition and rapacity. Their President and officers of state might have thrown off their modest exterior, and in time have be- come an aristocracy, vying with that of Rome in power and prodi- gality. But the diffusion of political knowledge renders this a consummation not much now to be feared. It is likelier, that, while America preserves her plain and frugal administration, the governments of older countries will throw off their super- fluous and expensive pageantry, and donning a plain, cheap, and working habit, become more respectable in appearance, as well as more useful and efficient. Our readers will not mistake us so far as to suppose that we would wish to deprive any government of the decent splendour that should surround it. But much of the 'tawdry tinsel which formerly was gazed on with ignorant awe, is !low surveyed with intelligent scorn. The time is gone by when it was necessary to purchase for Cato himself the respect of an English theatrical audience,bydressinghim in "long wig, floweid gown, and lacqueed chair." The physical splendour requisite to add dignity to the government even of a monarch, will not be very costly, provided it is accompanied with that moral grandeur Which is bestowed by wisdom and patriotism. Governments being prone to profusion, it belongs to the People o Obeck this propensity; and the provision of our Constitution, Which vests in the Popular branch of the Government the exclu- sive power of regulating tho supplies, cannot be too much eulo- gized even by a DE LOLME. But DE LOLME eulogized as a substance, what was little more than a shadow in his time ; for it was then a mere illusion, that the House of Commons repre- sented the People. Things are different now ; and if the People are pinched by profuse expenditure in future, they will have themselves to blame.

The People themselves have, indeed, been by no means blamele is on the score of profusion, though they have been the sufferers by it. They are liable to gross errors and prejudices on the subject of the advantage and honour of the country ; they are apt to be stirred up to violent animosities on frivolous grounds ; and seas of blood have been spilt, mountains of treasure squandered, in conse- quence of popular clamour. It is, however, a blessing attoadinz the real Representation of the People, that even the ignorant and prejudiced have generally discernment enough to choose for their representatives the liberal and enlightened.

Economy will he an object of paramount importance in the Reformed Parliament. The People are crushed by the weight of the public burdens. These enter so much into the price of every production of domestic industry, that our manufacturers, hr place of supplying other nations, can scarcely prevent themselvesl-. from being undersold in our own markets, unless by obtaining: from Government a protection against the public at large, who are compelled to buy commodities at the enhanced price at which the manufacturers can afford to make them. Were this protection to benefit the manufacturers, it might be something ; but, even in regard to them, it is hollow and deceitful. It is this policy which compels the people to pay a monopoly price for bread,, while the farmers are bankrupt and the labourers on the parish:. Nothing will relieve the manufacturers, the farmers, and the whole people from these evils, but a free interchange of the pro- ducts of industry. But the way for this must be paved by re- ducing, to the utmost possible limit, the burdens which press upon the industry of Great Britain.

We say, these burdens must be reduced to the utmost possible limit; and therefore, in considering whether or not any article or public expense is to be continued, the only question is, whether or not it is ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY. This principle, it is quite plain, must be rigorouslyacted upon, at a time when, oven after the Public Expenditure is pared down to the greatest practicable extent, the People will still be burdened beyond what they can bear without much suffering. But the principle is one which.

ought to be acted upon at all times. " Ce n'est point," says MONTESQUIEU, "a. cc que le peuple peut donner qu'il fau t mesurer les revenus publics, mais A ce qu'il doit donner;"--whatever the.

People can afford, the expenditure of the State gbould always be measured on the strictest scale of gmleply, Individuals will Ind more profitable employments for their surplus means, than allowing them to be spent' by Government on what it may con- sider merely beneficial objects.

Nothing, indeed, is beneficial to a nation, but what is necessary. The expense of government, of administering the laws, and of the xtational defence, is all that is either necessary or beneficial. Ex- pense bestowed merely on national splendour is neither. If a public building is necessary, let it be built; and the same expense will snake it elegant that would make it hideous,—for good and bad taste have nothing to do with expense. As to the notion of build- ing for the sake of encouraging architecture, it is about as wise as taking physic to encourage the doctor. IndrA, the idea of Govern- ment patronage of the fine arts, or of litc,rature, is generally ex- ploded: it is perfectly understood by architects, painters, sculp- tors, and men of letters, that their only efficient patron is the It is with the view of discovering what part of the Public Ex- penditure is necessary, what is superfluous, and what is absolutely wasteful, that we have undertaken the investigation of which we mow present the results. We have analyzed, more or less in detail, every branch of the subject; and (without anticipating what follows) we will venture to say, that we have shown that re- ductions, perfectly safe, and even beinylcial to the whole public service, are practicable to an extent which many of our readers would not, without this evidence, have believed.

If any thing could heighten the necessity for the most unspar- ing reduction, it would be, that one great branch of expenditure— indeed, four-sevenths of the whole—cannot be touched. Of course, we allude to the interest of the National Debt. To diminish this heavy, but just burden, by paying the public creditors in debased money, or any similar device, would be a breach of faith so scan- dalous and disgraceful, that we feel perfectly assured it will never be sanctioned by the Government, the Parliament, or the People of this country.

It is often foolishly argued against particular reductions of ex- penditure, that they are of no consequence, for that their benefit, when divided among the whole population, becomes imperceptible.

• " Why so much anxiety to cut off 150,000/. from the expenditure, when, divided among sixteen or among twenty-four millions of people, it only amounts to twopenee or to three-halfpence a head?" 33ut these arguers forget, or would have us to forget, that by lopping off 150,000/. from the expenditure, some entire tax, that presses unduly on some particular class, or seriously injures some branch of industry, could be removed. Twopence a head on the population of Great Britain is equal to the whole amount of the hop-duty. Or take Britain and Ireland, led. would give the commercial classes the benefit of Advertisements duty-free ; 41d. would extinguish the odious Newspaper-tax. Let us hear no more, then, of the shabbiness of small savings: and let us bear in mind, that great savings, as well as small, lie within the reach of a searching and just economy.

Sinecures are now out of the question. And not only should every sinecure office be abolished, but the salaries of public servants in even the efficient departments of the State ought to be inquired into, and reduced to the scale of fair remuneration for "work and service" performed. Almost all of them are much overpaid; and the consequence is, not only that the public money is wasted, but the business is not done. The negligence of every Public officer is in the direct ratio of the amount of his emolument beyond a fair remuneration for his labour. The business is generally left to a deputy; and while the principal is paid for lounging in his office just long enough to save appearances, the deputy receives a separate salary, also from the public, for doing the whole business. Pay the principal liberally, but reasonably ; and he will do the business himself, without any deputy.

Moreover, by reducing to a reasonable allowance all the sala- ries directly paid by Government, we shall indirectly relieve the Country to a great amount, by causing a reduction in the salaries of multitudes of offices, all over the kingdom, which are paid out of County rates, fees exacted on law proceedings, and other local funds, and which in their scale of emolument are regulated by the offices paid by Government.

Profusion has generally been the immediate cause of the over- throw of old governments and the ruin of empires. In ancient Rome, the profligate expenditure of the Emperor and his court was supported by grinding exactions; while in the remotest pro- vinces every proconsul was a miniature despot, surrounded by a court, and served by functionaries, who followed in all things the example set in Rome itself. Hence exasperation, insurrections, and rebellions,—unceasing convulsions, followed by a weakness that rendered the Empire an easy prey to the hardy invaders of the North. In modern France, the growing deficit in the finances, which swelled at last to a bulk with which it was in tam n to contend, gave rise to those disorders which broke in pieces the frame of Government, and overturned the whole structure of society. Such hitherto has been the fate of old governments ; and such may our own be, when the weakness of old ' age shall come upon us. We are old, indeed, if our years are counted ; but it is, we trust, a green old age ; and, in the Great Charter of 1832, we have drunk an elixir vita?, which, if' it cannot confer immortality, will at least bestow on us a new lease of existence as a nation.

Previous page

Previous page