Levin One and Levin Two

Christopher Booker

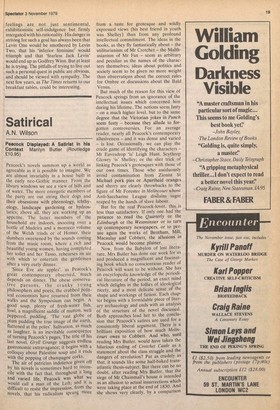

Taking Sides Bernard Levin (Cape £6.50) There has been no more dramatic journalistic debut (or near-debut) in my lifetime than that which took place on 25 January 1957 when the Spectator launched a new 'Westminster Commentary', mysteriously signed only with the pseudonym 'Taper'. It is almost impossible now to recapture the force with which this column cut through the deferential fog which had settled over English political life in the early Fifties. Week after week, here was an entirely new voice — irreverent, savagely funny. turning the solemn proceedings of the House of Commons into farce, peopled with such suddenly memorable grotesques as 'Sir Shortly Floorcross' and 'Sir Reginald Bullying-Manner'. Gradually it became public knowledge that 'Taper' was a 29year-old man called Bernard Levin — and over the past two decades, as he has moved on, first to the Daily Express and Mail, finally since 1970 to his present resting place as chief columnist of The Times, Levin has become the nearest thing to a national institution of any journalist who has emerged in this country since the war.

It has perhaps been inevitable that so compulsively industrious and so deliberately self-projecting a journalist as Levin should have attracted over the years such a mixed reception. As he has sounded off, in interminable millions of words, about the British political scene, Wagner, Soviet dissidents and all his favourite themes, he has alternately delighted and enraged, amused and bored to exceptional extremes. But one of the deeper reasons why his reception has been so mixed, and why many readers are perhaps never quite sure where they stand on Levin, is not so much that he, like any journalist, has his on-days and his off-days, but that over the years we have come to recognise two almost distinct journalists writing under the same name.

On the one hand, there is Levin One, heir to the Taper of the late Fifties — fearless, hard-headed critic of politicians and bureaucrats, unswerving foe to all forms of totalitarianism, whether of the Soviet or the South African variety, and to left-wing ideologues of all kinds, whether they be trade union bullies or Miss Vanessa Redgrave. This Levin writes in a taut, impatient style, is capable of ruthless dissection of cant and rubbish, is often brilliantly, sarcastically funny. Over the years he has undoubtedly moved, as the cliché has it, to the right, but at the heart of Levin One there has always been a fundamental consistency — that he is a champion of individual freedom (and it is this which has sometimes led him to seem to cut confusingly across more familiar ideological lines, as when he has sided with the 'Right' over America's involvement in Vietnam, or with the 'Left' over such issues as apartheid and the censorship of pornography).

Increasingly, however, over the past 15 years or so, there has peeped out from behind Levin One a deutero-Levin. In my mind's eye 1 always see this Levin Two sitting in a pink jacket at a high chair, with his legs scarcely touching the ground, surrounded by adoring middle-aged ladies and preparing to tuck in to some disgusting, French-sauce-smothered meal. This is the sentimental, soft-centred, imdulgent Levin, who writes about lobster-eating competitions with Robin Day, cats, his fear of spiders and his passion for Miss Kin i Te Kanawa, and, alas, all too often about music (as in the notoriously soppy piece where he • described all the music of Bach as sounding to him as if it were in the minor key). Levin Two is pur et simple a purveyor of schmaltz and schlag, so lacking in the rationality, the strength and the masculinity of Levin One that one wonders sometimes how they can be the same person.

Being essentially a journalist, Mr Levin has only ventured once before into hard covers (and even then, The Pendulum Years, his account of the Sixties, was more a succession of articles than a book). But he has now, rather more openly, produced an anthology of his journalism — most of it dating from the past ten years on the Times (there is not one article, to my regret, from the 'Taper' period). And above all it demdmstrates the extraordinary dichotomy between the two Levins.

Levin One, for instance, contributes a rollicking attack on one of A.L. Rowse's interminably conceited books on Shakespeare; a merciless dissection of the campaign of a body calling itself 'Librarians for Social Change' to root out 'sexism, racism and age-ism' from the shelves of Britain's public libraries; a marvellously funny and savage review from the Observer of Vita Sackville-West's grotesque Lesbian diaries. The same unmistakable voice analyses the charge that the Oberammergau Passion Play is 'anti-Semitic', or hangs a whole brilliant essay on the report that Miss Bridget Dugdale's first comment on her baby born in prison was 'he will be a guerilla'. Not the least achievement of Levin One in recent years, of course, has been his consistent effort to bring to light some of the more obscure and terrible goings-on in the vast area of the world controlled by Communist governments — and as one of the first journalists to publi cise the almost incredible horrors which succeeded the Khmer Rouge take-over in Cambodia, he was right to re-publish two of those articles three years later, even though their gist has now become common knowledge.

Alas, there are also the contributions of Levin Two, about which, for this reviewer's taste, the less said the better. There is, thank heavens, no food pornography (apart from a stray reference to something called 'Pere Bise's poularde braisee a la crème d'estragon'). But there are some typical 'Mother's Boy' pieces about going to the Cup Final and Ascot, and having a window box; there is a schmaltzy piece on Schubert and another on the retirement of his hairdresser (who, interestingly, does not emerge from this supposed 'personal tribute' as a human being at all); worst of all, there are some of Levin's self-consciously 'satirical' pieces, about lawyers with names like 'Preposterous Attorney QC', or a pair of tasteless items (following the death of Steve Biko) about the persecution of 'John Cheekykaffir' by the Minister of Justice `Mr Sjambok-Goering'. What could have possessed Mr Levin to include these, and not one of the most genuinely funny pieces of journalism I can remember, his article on the trial of the lady who was accused of cruelty to prawns, I cannot think. There are also a number of pieces which veer uneasily between Levin One and Levin Two — such as the celebrated account of his mother's experiences with the North Thames Gas Board over a faulty geyser, and his description of meeting Solzhenitsyn. This begins with a memorable snapshot ('Alexander Isayevich Solzhenitsyn came into the room smiling, and that was the first surprise, for he is one of those people whose faces are frozen by the camera, and he is consequently almost always portrayed looking solemn, if not actually seeming to scowl; in fact he smiles very readily, and laughs a great deal') but peters out in the end into pure schlag: 'Alexander Isayevich, do not despair just yet. We understand'. And of course this sort of thing raises the real question about the split between the two Levins — which is, where does he find within himself that fundamental 'centre from which he can write truly seriously, in the way he obviously wishes to. He is fine so long as he is on the attack, in his hardheaded 'masculine' persona. Where he falls down, and where the inferiority show.s through to the point of embarrassment, is where he calls on his more side, side, when he expresses his feelings and intuitions. Two of the very few pieces in the book where he manages to be both positive and unsentimental (well, almost) at the same time are his surprising account of the friendship he formed with Field-Marshal Montgomery, and his splendid review last year of Cosima Wagner's Diaries. Here at last is a hint of that which Mr Levin has shown many signs in recent years that he is straining for — that deeper centre where the two sides of him can be brought together, and where his • feelings are not just sentimental, exhibitionistic self-indulgence but firmly intergated with his rationality. His danger in striving for such a goal has always been that Levin One would be smothered by Levin Two, that his 'inferior feminine' would triumph and that 'fearless Jack Levin' would end up as Godfrey Winn. But at least , he is trying. The pitfalls of trying to live out , such a personal quest in public are obvious, and should be viewed with sympathy. The next few years, as The Times returns to our breakfast tables, could be interesting.

Previous page

Previous page