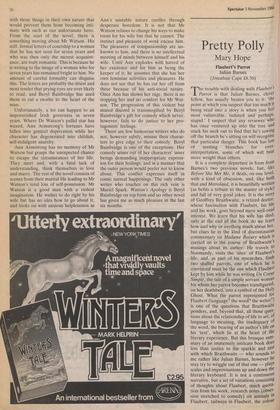

Pretty Polly

Mary Hope

Flaubert's Parrot Julian Barnes (Jonathan Cape £8.50)

The trouble with dealing with Flaubert's Parrot is that Julian Barnes, clever fellow, has usually beaten you to it: 'the I point at which you suspect that too much s being read into a story is when you feel most vulnerable, isolated and perhaps, stupid.' I suspect that any reviewer who has once ventured up into the tree and stuck his neck out to find that he's sawing off the branch he's sitting on will recognise that particular danger. This book has lots of inviting branches for over- interpretation, some of which will bear more weight than others.

It is a complete departure in form from Barnes's two previous novels, but, like Before She Met Me, it deals, on one level, with a kind of obsession, and, like both that and Metroland, it is beautifully written (as befits a tribute to the master of style) and full of very good jokes. It is the story of Geoffrey Braithwaite, a retired doctor. whose fascination with Flaubert, his life and his work, goes beyond mere well-read interest. We learn that his wife has died; only at the end of the book do we learn how and why or anything much about her, but clues lie in the kind of discontinuous commentary on Madame Bovary which is carried on in the course of Braithwaite 's musings about its author. He travels to Normandy, visits the 'sites' of Flaubert's life, and, as part of his researches, finds two stuffed parrots, one of which he Is convinced must be the one which Flaubert kept by him while he was writing tin Coeur Simple, the tale of a simple servant woman for whom her parrot becomes transfigured, on her deathbed, into a symbol of the Holy Ghost. What the parrot represented for Flaubert (language? the word? the writer?) is one of the questions that Braithwaite ponders, and, beyond that, all those ques- tions about the relationship of life to art, of language to meaning, the inadequacy of the word, the bearing of an author's life on his 'text', which lie at the heart of the literary experience. But this brusque sum- mary of an immensely intricate book does less than justice to the sparkle and zest with which Braithwaite — who sounds to me rather like Julian Barnes, however he may try to wriggle out of that one — plays scales and improvisations up and down the literary keyboard. It is not a continuous narrative, but a set of variations consisting of thoughts about Flaubert, much quota- tion from his work, research notes (obses- sion stretched to comedy) on animals In Flaubert, railways in Flaubert, the colour of Emma Bovary's eyes, irony, coinci- dence, books Flaubert never wrote. There is a scathing attack on the late Enid Starkie, leading to a, condemnation of critics as a breed, from which he moves to an exposé of 'mistakes' in literature, slip- shod writing in general (including, if I am not mistaken, a tilt at the young author of Metroland.) There is a hilarious list of books which he (Braithwaite, or really Barnes?) would ban, including novels set in Oxford or Cambridge, a quota system for novels set in South America, and a partial ban on growing-up novels (one per author). Then there is a pastiche account of Flaubert's relationship with Louise Col- et, told by her, and a set of cod exam Papers: 'It has become clear to the examin- ers in recent years that candidates are finding it increasingly difficult to disting- uish between Art and Life . . Consider the relationship between Art and Life suggested by any two of the following statements or situations . .

So wheels within wheels. What Barnes is doing is using a study of a writer who, above all, believed in not being seen ('the author in his book must be like God in His universe, everywhere present and nowhere visible'), to talk about writing and its relationship to the 'real' world, and, to tie You in further knots, sets his thoughts inside a novel — though, actually, as a novel, not a very 'good' one. But it's rather a good book — as you see, once you get into this kind of tricksy area you can lead Your readers on a long, long way, cutting off all avenues of escape, especially if you do a series of immensely enjoyable turns On the way. Braithwaite is fascin- ated by the past — 'Is it just that the past seems to contain more local colour than the present' — as Barnes has been in his previous books, as, he implies, any writer must be. And, this is the difficult one, by love: 'With a lover, a wife, when you find the worst — be it infidelity, madness or suicidal spark — you are almost relieved. Life is as I thought it was; shall we now celebrate this disappointment? With a wri- ter you love, the instinct is to defend . . And the relationship between the author and his characters? 'Madame Bovary, c'est Atoi', said Flaubert, as every schoolboy knows. The obsession of writing and the obsession of love are, perhaps, not too far removed: didn't the jealous Graham in Before She Met Me confess to wanting to be his wife before he killed her? The only way You can be someone else, is, like Flaubert, Or Barnes, to create them. And so we are back to God, and Flaubert, and writing, and the closed circle that Barnes has Constructed for us.

It is, as you see, an obsessional book; and, like all obsessions, it can infect bystanders. As a way of writing about writing about writing, it is a fascinating exercise; all the right questions are asked however, a display of dazzling virtuosity. It is, nowever, notable that in Braithwaite's list of books to be banned, books about Writing books do not appear.

Previous page

Previous page