The proper study of A Clark is Clark

John Redwood

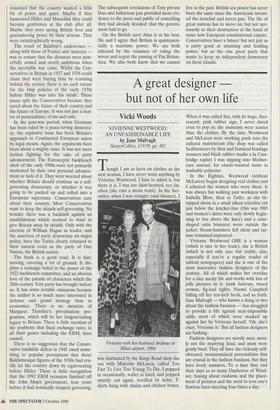

THE TORIES by Alan Clark Weidenfeld, £20, pp. 494 Alan Clark is one of the great charac- ters of the day, a larger than life figure who refuses to be pushed around by spin doc- tors or by the new pressures for conformity in a political party. His interests make him a better diarist than historian. The diary is the right format for his amusing, cynical savoir faire. There the unkind jibes about colleagues or the deliberately well-turned phrase which captures but half a truth, if truth at all, can amuse the reader. The diaries reveal most about Alan himself, rather less about those he describes. That is the nature of their success.

His history of the Tories reveals more of the same strengths and weaknesses of Alan as an observer and writer. If he belongs to any school of history it is Namierite. He sees the history of the Tory party as a history of personal jealousies, factions and squabbles related ultimately to one end: the gaining and holding of power for par- ticular individuals, or occasionally for the party as a whole.

Sometimes the insights he has into personal rivalries, as with his descriptions of Churchill and Eden or Baldwin and his critics are well done. He is right to say that personality and faction have been important in the extraordinary story of 20th-century Conservatism — just as they have been in 20th-century left-wing politics as well. He reminds us that leaders who urged loyalty on their party often led earlier lives of dissent, or had plotted their way to the top against the previous leader- ship. He describes a party which could win and hold power despite the disagreements and squabbles between the leading figures.

He is wrong to play down the passions and great issues which make the 20th cen- tury different from the 18th which Namier was describing. There have been two huge, overarching issues of 20th-century foreign policy which have bedevilled the Conserva- tive party as the party of government. The first was appeasement. The establishment under Baldwin judged that the mood of the country was against a war or conflict with Germany in the 1930s. They were early advocates of following focus groups. They reasoned that the country wanted a little bit of peace and quiet. Maybe if they humoured Hitler and Mussolini they could become gentlemen at the club after all. Maybe they were saving British lives and guaranteeing peace by their actions. They were catastrophically wrong.

The result of Baldwin's endeavours along with those of France and America was to ensure that the dictators were pow- erfully armed and overly ambitious when the inevitable war came. Whilst the Con- servatives in Britain in 1937 and 1938 could claim they were buying time by rearming behind the scenes, there is no such excuse for the limp policies of the early 1930s before Hitler was into his stride. These issues split the Conservatives because they cared about the future of their country and the future of Europe. It was not just a mat- ter of personalities, of ins and outs.

In the post-war period, when Germany has been ruled by a peace-loving democra- cy, the explosive issue has been Britain's approach to Continental European union by legal means. Again, the arguments have been about a mighty issue. It was not mere faction fighting for the sake of petty advancement. The Eurosceptic backbench choir of the early 1990s were not primarily motivated by their own personal advance- ment or lack of it. They were worried about whether Britain should continue as a self- governing democracy, or whether it was going to be packed up and rolled into a European superstate. Conservatives care about their country. Most Conservatives want to keep the islands self-governing. No wonder there was a backlash against an establishment which seemed to want to give Britain away by stealth. Only with the election of William Hague as leader, and the assertion of party democracy on major policy, have the Tories clearly returned to their natural roots as the party of One Nation, the British nation.

The book is a good read. It is fast- moving, covering a lot of ground. It dis- plays a nostalgic belief in the power of the 1922 backbench committee, and an obvious love of the parade of characters which the 20th-century Tory party has brought before us. It has some notable omissions because the author is so much more interested in defence and grand strategy than in economics. There is no mention of Margaret Thatcher's privatisation pro- gramme, which will be her longest-lasting legacy to Britain. There is little mention of the problems that fixed exchange rates, in all their guises including the ERM, have caused.

There is no suggestion that the Conser- vative landslide defeat in 1945 owed some- thing to popular perceptions that those Baldwinesque figures of the 1930s had cru- elly let the country down by equivocating before Hitler. There is little recognition that the 1992 ERM recession finished off the John Major government, four years before it had nominally stopped governing. The subsequent revelations of Tory private lives and behaviour just provided more evi- dence to the press and public of something they had already decided: that the govern- ment had to go.

On the British navy Alan is at his best. He and I agree that Britain is quintessen- tially a maritime power. We are both infected by the romance of ruling the waves and regret the passing of Pax Britan- nica. We also both know that we cannot live in the past. British sea power has never been the same since the Americans invent- ed the ironclad and turret gun. The life of great nations has to move on, but not nec- essarily to their destruction at the hand of some new European constitutional empire. Conservatives have a future: but not just as a party good at attaining and holding power, but as the one great party that wants to keep an independent democracy on these islands.

Previous page

Previous page