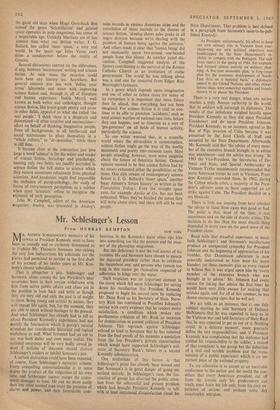

Mr. Schlesinger's Lesson

From MURRAY KEMPTON NEW YORK

MR. ARTHUR SCHLESINGER'S memoirs of his service to President Kennedy seem to have been so roundly and so curiously denounced as to frighten Mr. Theodore Sorensen into exising the very few indiscretions his solicitude for the pieties had permitted to survive in the first draft of his account of his twelve years as Mr. Ken- nedy's closest subordinate.

That is altogether a pity. Schlesinger and Sorensen, alone among the late President's near associates, have in their sorrow withdrawn with him from active public affairs and alone are in the position to look back and write as though they are very old and only the past is of weight to them. Being young and activist by nature, they will engage life again, but, for the moment, they are able to speak without hostages to the present. And what Schlesinger has already had to tell us about President Kennedy's experiences had not merely the fascination which is gossip's natural attendant but considerable historical and topical usefulness as well. What Sorensen had set out to say was both duller and even more useful. The national awareness will be very badly served in- deed if notions of decorum should distract Schlesinger's readers or inhibit Sorensen's pen.

A certain distraction could have been expected, of course, from Schlesinger's narrative scheme. Every compelling conversationalist is to some degree the product of the vulgarities of his own time, and Schlesinger cannot escape the conse- quent damages to tone. He can no more easily than any other normal man resist the presence of charm and power; and their formidable com-

bination in the Kennedys quite often tips him into something too like the posture and the man- ner of the photoplay magazines.

But this deficiency is not the real /source of his troubles. He and Sorensen have chosen to mourn the departed president rather than to celebrate the incumbent one; And persons who remain too long in this stance get themselves suspected of adherence to kings over the water.

Such suspicion was an important element in the storm which fell upon Schlesinger for setting down his recollection that President Kennedy proposed to begin his second term by replacing Mr. Dean Rusk as his Secretary of State. Secre- tary Rusk has continued in President Johnson's service with every evidence that he renders entire satisfaction, a condition which makes any posthumous criticism of Mr..Rusk an occasion for denunciation as present criticism of President Johnson. This reproach against Schlesinger echoed so loud to Sorensen that he has removed from the final proofs of his memoirs a quotation from the late President's private conversation which would have supported Schlesinger's esti- mate of Secretary Rusk's future in a second Kennedy administration.

One misfortune of this furore is that Schlesinger's point has already been missed and that Sorensen's is in great danger of going un- noticed entirely. In Schlesinger's case, the fas- cination of gossip has diverted the public atten- tion from the substantial and present problem which had brought President Kennedy to talk with at least occasional dissatisfaction about his

State Department. That problem is best defined in a paragraph from Sorensen's soon-to-be-pub- lished Kennedy:

As President, unfortunately, his effort to keep our own military role in Vietnam from over- shadowing our own political objectives was handicapped by the State Department's in- ability to compete with the Pentagon. The task force report in the spring of 1961, for example, had focused almost entirely on military plan- ning. A five-year economic plan, 'a long-range plan for the economic development of South- East Asia on a regional basis,' a diplomatic appeal to the United Nations, and other miscel- lanous ideas, were somewhat vaguley and loosely thrown in to please the President.

There is a very real danger, when any nation reaches a truly Roman authority in the world, that its soldiers will outweigh its diplomats. The results of that imbalance weighed heavily upon President Kennedy as they did upon President Eisenhower and do upon President Johnson. President Kennedy, as an instance, agreed to the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba because it was presented by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and accepted by the State Department. Afterwards, Mr. Kennedy said that 'the advice of every mem- ber of the executive branch brought in to advise was unanimous—and the advice was wrong.' In 1963 the Vice-President, the Secretaries of De- fence and State, and Special Ambassador to Vietnam Taylor unanimously recommended that more American troops be sent to Vietnam. Presi- dent Kennedy overruled them. In 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis, a majority of the Presi- dent's advisers seem to have supported an air strike against Cuba. The President decided on a sea blockade.

There is little use arguing from here whether the advice in these three cases was good or bad. The point is that, most of the time, it was unanimous and on the side of drastic action. The decision to do less than the most drastic thing depended in every case on the good sense of the President alone.

Read with that dreadful experience in mind. both Schlesinger's and Sorensen's recollections produce an unexpected sympathy for President Johnson and the beginning of appreciation of his troubles. Our Dominican adventure is now generally understood to have been his worst blunder; yet these memoirs give us every reason to believe that it was urged upon him by 'every member of the executive branch who was brought in to advise.' Mr. Johnson had every excuse for taking that advice the first time; he would have very little excuse for making that mistake again, and, for all of this summer, he has shown encouraging signs that he will not.

We are told, as an instance, that at one July cabinet meeting he told Secretary of Defence McNamara that he was expected to keep us in the Vietnam war and told Secretary of State Rusk that he was expected to get us out of it. Nothing could, in a delicate moment, more precisely define the two responsibilities; and, if President Kennedy was complaining that the diplomat had yielded his responsibility to the soldier, a record of that complaint is not gossip but the definition of a real and terrible problem and the 'trans- mission of a public experience which is an im- portant piece of the national property.

To say otherwise is to accept as an inevitable misfortune to the nation and the world the con- dition that every American president, cut off from the lessons only his predecessors can teach, must learn his job only from his own ex- perience of serious and perhaps some day catastrophic mistakes.

Previous page

Previous page