Travel

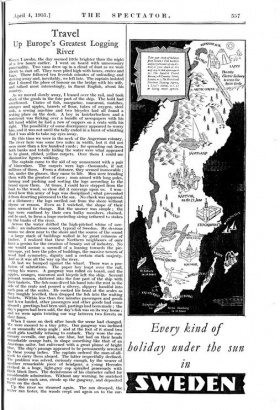

Up Europe's Greatest Logging

River

win,: I awoke, the day seemed little brighter than the night of a few hours earlier. I went on board with unnecessary punctuality. Two vans drew up in a loud of dust as we were about to cast off. They were piled high with boxes, crates and bags. There followed ten feverish minutes of unloading and stowing away and, inevitably, we left late. The captain insisted that I shared the place of honour on the bridge with his wife, and talked most interestingly, in -fluent English, about his country.

As we moved slowly away, I leaned over the rail, and took stock of the goods in the fore part of the ship. The hold had overflowed. Crates of fish, margarine, macaroni, matches, oranges and apples, barrels of flour, tubes of oxygen, steel rods, a sewing machine and two bicycles had all folind a resting place on the deck. A boy in knickerbockers and a waistcoat was flicking over a bundle of newspapers with his left hand whilst he laid a row of coppers on a crate with his right. The possibility of some discrepancy appeared to worry him, and it was not until the tally ended in a burst of whistling that I was able to take my eyes away.

By this time we were in the neck of the Angerman estuary. The river here was some two miles in width, but it did not seem more than a few hundred yards ; for spreading out from both banks and totally hiding the water were what appeared to be giant, ribbed, yellow carpets. Over them I could see diminutive figures walking.

The captain came to the aid of my amazement with a pair of binoculars. The carpets were logs—thousands, if not millions of them. From a distance, they seemed immovable ; but, under the glasses, they came to life. Men were treading them with the greatest of ease ; men armed with long poles, turning and pushing and sorting the logs according to the brand upon them. At times, I could have stepped from the boat to the wood, so close did it converge upon us. I won- dered how this army of logs was disciplined ; what prevented it from deserting piecemeal to the sea. No check was apparent at a distance ; the logs swelled out from the shore without rhyme or reason. Even as I watched, the shape of their mass seemed to change. But the answer was simple ; the logs were confined by their own bulky members, chained, end to end, to form a huge encircling string tethered to stakes by the banks of the river.

Across the water drifted the high-pitched whine of saw- mills : an industrious sound, typical of Sweden. By devious means we drew near to the shore and the source of the sound --a large stack of- buildings walled in by great columns of timber. I realized that these Northern neighbours of ours have a genius for the creation of beauty out of industry. No one would accuse a sawmill of a leaning towards the pic- turesque, yet here the piles of buildings, the massive towers of wood had symmetry, dignity and a certain stark majesty. And so it was all the way up the river.

At last we bumped against the wharf. There was a pro- fusion of salutations. 'The paper boy leapt over the rail, crying his wares. A gangway was rolled on board, and the apples, oranges, macaroni and bicycle left the ship. Several peasant women, clattered- into the fore part of the ship with their baskets. The fish-man dived his hand into the rent in the side of the crate and poured a silvery, slippery handful into each pan of the scales. He cocked his head at the scales as they roughly levelled, then dropped the fish into the waiting baskets. Within less than five minutes passengers and goods had b!en landed, other passengers and other goods had come aboard ; greetings had been said, partings had been made ; the day's papers had been sold, the day's fish was on its way home ; and we were again twisting our way between two forests on their faces.

When I came on deck after lunch the scene had changed. We were moored to a tiny jetty. Our gangway was inclined at an unusually steep angle ; and at the foot of it stood two small girls tearfully refusing to embark. They wore the cus- tomary overalls, one pink, one blue, but had on their heads remarkable orange hats, in shape something like that of an American sailor, but enlivened with a great plume of bright blue. The ship's passage appeared to be permanently arrested by these young ladies. The captain ordered the man-of-all- work to carry them aboard. The latter respectfully declined. The problem was solved, curiously enough, by the wearer of another remarkable piece of headgear, a young Hercules clothed in a huge, light-grey cap spiralled generously with thick black lines. The decisiveness of his character called for Considerable admiration. Without any warning, he snatched a girl under each arm, strode up the gangway, and deposited them on the deck.

Up the river we steamed again. The sun drooped, the water ran faster, the woods crept out again on to the sur- rounding hills, and Solleftea drew near. Then, suddenly, we ran into the logs. I heard a tearing sound on the hills above, there was a volley of tremendous splashes, and hundreds of logs suddenly reared their yellow bodies out of the water before us. This happened all the way to Solleftea. The loggers were sending the trees down the river. They branded them, rolled them to the edge of the hills, and gave them a push. The seaward flow of the water did the rest. In a few minutes the river was choked with them. We had to run them down. It was a fascinating experience. These masses of timber, many much larger than our steamer, and the width of a man's waist, drove straight at us. Sometimes our bows flung them aside to slide greasily upon each other's backs. More often we would go right over them. There would be a muffled boom, for all the world like long-range gun fire, as they struck our sides • our little boat would quiver and the logs would be spurned up, turning mad spirals, in our wake. It was a strange but wonderful introduction to my quiet room in the hotel at

Previous page

Previous page