A Doctor's Journal

Smoking-Sickness

y HEAR that a well-known insurance company proposes to grant a 10 per cent. reduction on sickness and accident policies to members of the National Society of Non-Smokers. This doesn't surprise me, and if I were the managing director of the company I would do the same. In the first place, it is sensible to link sickness and accidents together. Repeated accidents are a symptom of sickness—the disorder, accident- proneness, which has been quite well studied and documented. In sufferers from this disorder the ' impulse to get into an accident, when it is active, operates outside conscious awareness and is thus not under control of the 'self.' These folk will injure themselves, however innocent the environ- ment, even to tripping over their own feet or shutting a finger in the door.

In the second place, the heavy smoker is more liable to sickness of one kind or another. It seems very probable from the evidence that heavy smoking and cancer of the lung are asso- ciated, though it may not be a simple cause-and- effect association. After all, what makes a man buy and consume forty cigarettes a day? What need is he trying to satisfy? I have often heard the compulsive smoker say that he is quite sickened by tobacco, yet can't stop. Might it be that behind both the smoking and the lung cancer is a third factor—an internal force which works in the dark? In some smokers, at any rate, there is a vicious-circle reaction--each fag pre- disposes to the next. Therapists who use hypnosis have told me that the tobacco habit can be broken by their method, and I imagine it is the vicious- circle smoker who is most likely to benefit. Where smoking is a sign of a more deep-seated tension, it will not be easily relinquished. It is, in its way, a form of self-injury, like the compul- sive accident.

Travelling this morning from Waterloo to Southampton on the SR, I was fascinated, as always, by the long vistas of suburbia, that end- lessly repeated pattern of identical cubes, like cells in a hive. Stephen Taylor gave the illness of suburbia a name in the Lancet in, I think, 1938. (Twenty years! I don't feel that much older.) He was writing about life in the sprawling new estates on the outskirts of cities, where it was considered always correct to keep oneself to oneself, and where the one-child family and the baby car were the height of ambition. Taylor ob- served that the physical health of the people was fair, but many of them suffered anxiety states and spells of depression; and he attributed these to boredom, loneliness and a false set of values.

'The suburban neurosis,' he called it : an apt title which soon became fashionable. The idea of social isolation as a cause of illness was newer then; more recently there was David Riesman's study of The Lonely Crowd. During the war, in cities at any rate, the isolation, so characteristic of the English, broke down under the pressure of a universal threat; people in shops, in queues, in the Tube, began talking to each other. When peace returned the taboo reappeared, but it has never been quite so strong as before.

What happens in suburbia now? In the big municipal estates and the new towns do people have the feeling of belonging? Or do they It

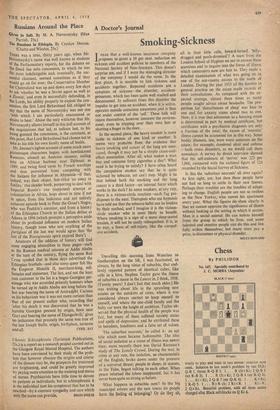

all in their little cells, inward-turned, 'telly- drugged and pools-drowned'? A team from the London School of Hygiene set out to answer these questions and to inquire into the forms of illness which commuters now are heir to. They made a detailed examination of what was going on in one of the out-county estates to the north of London. During the year 1953 all the doctors in general practice on the estate made records of their consultations. As compared with the ex- pected average, almost three times as many people sought advice about headache. The pro- portion for 'disturbances of sleep' was four to one and for anxiety states about two to one. Now, it is true that admission to a housing estate is determined in part by medical certificate, but certificates with a psychiatric diagnosis are only a fraction of the total; the excess of 'neurotic' illness cannot be accounted for in this way. Some bodily illnesses, too, were more common on the estate; for example, duodenal ulcer and asthma —both stress disorders, as we would call them nowadays. A survey by direct interview showed that the self-estimate of 'nerves' was 223 per 1,000, compared with the national figure of 126 recorded by the Social Survey of Sickness.

Is this the 'suburban neurosis' all over again? At first sight, yes; but then these people have not had so long to settle in their new homes. Perhaps their troubles are the troubles of adapt- ing to change. English people are not so restless as the New Yorker, who moves his apartment every year. What the figures do show clearly is that we cannot appraise the significance of illness without looking at the setting in which it occurs. Man is a social animal. He can isolate himself from the group in which he lives, and some talented and creative people can do this and live fully within themselves; but many must pay a price, in discontent or physical disorder.

Previous page

Previous page