The lesson of the master

Kingsley Amis

Rendezvous with Rama Arthur C. Clarke (Gollancz C2.00) At fifty-six Arthur C. Clarke is still the leading science-fiction writer of his generation.

generation ', that slippery term, I mean in the present case those who started their careers between 1940 and that time in the mid-'60s when the genre began to be afflicted by modernism.) Clarke's first story was published in 1946; since then he has brought out nearly fifty books, some of them general works on the future of space-flight and other technologies. The range of his fiction is wide indeed, from severely probable, day-after-tomorrow tales of action (A Fall of Moondust) to far-off visions of a humanity on the verge of becoming something else (Childhood's End), Even at its boldest, his writing is sharp, lucid and logical, embodying imagination in the true sense of the word: common sense With wings. While his contemporaries repeat themselves at declining levels of energy, and blunder through the arid wastes of experimentation, Clarke continues to invent as he has always done.

Rendezvous With 'Rama might have been expressly designed to show, against a lot of evidence, that the old vein is not worked out. With almost cynical aplomb, the author takes some of the hoariest themes in the whole science-fiction repertory and blends them Into a fresh and genuinely exciting whole. The year is 2131, and the habitable worlds of the solar system have been colonised. A body

new to astronomers is found to be approaching the sun at a tremendous velocity. On inspection by space-probe, it turns out to be an artificial object, the first product of an alien civilisation to be encountered by man. Accordingly, the interplanetary craft Endeavour, under supervision by an ad hoc committee of the United Planets' Science Organisation, is dispatched to investigate and report.

Rama — the classical pantheon having long been used up, celestial novelties are given Hindu names — Rama is a vast cylinder, fifty kilometres long and twenty across. Its outside is practically featureless, but its inside, soon reached, is a sort of world that stretches round the skin of the cylinder. Thus there is no sky; to an observer standing at any given point (enabled to stand by the lateral spin that imparts pseudo-gravity) the ' land ' curves away and up on either side until it arches above his head. There is sea as well as land, a continuous ring-shaped body of water held in place by centrifugal force. And light is given by six regularly-spaced suns.

The exploratory team from Endeavour consists of just the right kind of people, efficient, tough, loyal, and otherwise differentiated only by their technical specialities: they would not do for a novel of character, but this is science fiction. They find structures that might be buildings without entrances, or machines with no ascertainable function; they encounter beings that are part robotic, part organic, engaged in mysterious tasks; they endure hurricanes caused by temperature changes as our sun starts to heat the outside of Rama; they sail the sea and meet a tidal wave; they find a single flower. Only after they have had to leave does Rama declare its purpose.

All this is visualised by a keen, expert eye and set down by a master hand, one that allows the various wonders to speak for themselves without stylistic fuss. Nothing is fudged and there are no loose ends, though a purist might complain that the attempt to sabotage the project, lively as its results are, is detachable, and that the superchimps in Endeavour (IQ 60, worth 2.75 men apiece for rough jobs) never leave the ship. On the other hand, there are some splendid throwaways, careless references to a tenth solar planet, Persephone, no doubt beyond Pluto, to the popular Church of Christ, Cosmonaut. And, with similar lightness, great cosmic absolutes are tossed in to give a far from light effect:

He was looking at the largest enclosed space ever seen by man . . in this one direction, parallel to the axis of Rama, the Sea was indeed completely flat, it might well be the only body of water in the universe of which this was true . .

Faster and faster Rama swept around the sun, moving now more swiftly than any object that had ever travelled through the solar system,

These and other uniquenesses are brilliantly twisted aside in the final sentence.

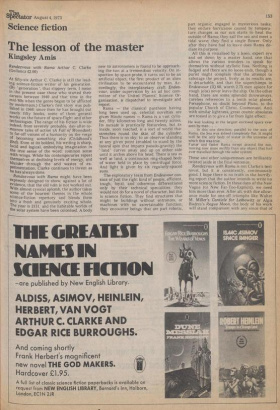

Rendezvous with Rama is not Clarke's best novel, but it is consistently, continuously good. I hope there is no truth in the horrifying report that the author intends to write no more science fiction, In these days of the New Vague (or New Ear-Too-Explicit), we need him more than ever. After all, with due allowance made for one-off triumphs like Walter M. Miller's Canticle for Leibowitz or Algis Budrys's Rogue Moon, the body of his work will stand comparison with any since that of

Previous page

Previous page