Keep smiling through

Jeremy Lewis

A CARTOON WAR: WORLD WAR TWO IN CARTOONS by Joseph Darracott

Leo Cooper, £16.50, pp. 153

THE BLITZ: THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF GEORGE RODGER

Penguin, £10.99, pp. 176

With morale to be sustained, troops to be kept amused, enemies to, be in- veighed against, profligate households to be kept on the straight and narrow — 'Switched on switches and turned on taps/ Makes happy Huns and joyful Japs' — and soaring newspaper circulations, it is not surprising that wartime cartoonists were a busy breed; or that Strube of the Express — the originator of the hen-pecked, down- trodden `Little Man', a clerk-like figure with a walrus moustache, spotted here after an air-raid inspecting his prize mar- row while his wife sits knitting in the shelter below (Is it all right now, Henry?' `Yes, not even scratched') — should have been earning from Beaverbrook the gigan- tic salary of £10,000 a year.

Nor is it surprising to learn that for all the grim effectiveness of, say, David Low at his starkest — the black, bat-like figures of Himmler and two SS henchmen de- scending as 'Angels of Peace' on the smoking ruins of a Belgian city — British cartoonists in particular tended to favour the humorous, humdrum approach — 'Business as Usual' — rather than the violence and savagery on offer in the pages of Simplicissimus in Germany (where the standard of work remained, to the end, astonishingly high) or Krokodil: an approach that may well have come natural- ly, but also reflected the findings of a Mass Observation survey, which reported that too much straightforward patriotism tended to be counter-productive.

Although one tends to think in terms of political, leader-page cartoonists — the most famous of whom, the New Zealander Low, worked for the Evening Standard — other practitioners contributed directly to the war effort or reflected, sometimes in strip-cartoon form, the progress of the war and the attitudes of civilians and service- men. Philip Boydell invented the ubi- quitous Squanderbug, a fanged, tear- shaped demon, covered with swastikas, who hurried about inciting weak-minded housewives to waste and overspend; while the admirable 'Fougasse' contributed free of charge to a series of official posters, the best-known of which — part of the `Care- less Talk Costs Lives' campaign — is subtitled `You never know who's listening' and shows two voluble matrons in a bus with, two rows behind, Goebbels and a bemedalled, baton-clutching Gdering drinking in every word.

Equally important was the whole busi- ness of keeping the troops amused; and few did a better job here than Norman Pett of the Mirror, whose curvaceous heroine, Jane, spent much of the war shedding items of clothing, not least when her clumsy boyfriend Georgie-Porgie inadver- tently trod on the hem of her evening gown ('R-r-i-p!'). On the other side of the Atlantic Popeye, L'il Abner, Superman and a temptress called Miss Lace were all hard at work: whereas a doleful,. spaniel- featured infantryman called `The Sad Sack' reflected the frustrations and the woes of the set-upon average soldier, an iron- jawed ex-boxer called Joe Palooka, embo- died — again in strip-cartoon form — a more vigorous patriotism, being moved to righteous wrath when 'someone steps on a pal's right to a good time (and all decent people are pals to him)'. Bugs Bunny was enlisted to insert grenades in Japanese ice-cream cones in a film called You're a Sap, Mr Jap, while a pleasing New Yorker cartoon showed a stout middle-aged lady addressing a roomful of other stout middle- aged ladies ('Miss Whitehead will tell us how to entertain sailors').

Such jollities seem a long way from the bleak, ferocious and often highly effective cartoons produced in Goebbels's Germany and via Agitprop in the Soviet Union. Mr Darracott's book covers every theatre of thewar, provides work from as far afield as Japan and New Zealand, and takes us from the Edwardian world of Bernard Partridge to that of Ronald Searle. One wishes he had given us more pictures and less text, too much of which consists of a blow-by- blow account of the war, in the midst of which information about the cartoonists themselves, and the conditions in which they worked, can be overlooked.

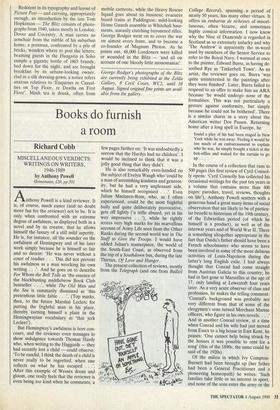

'Business as usual, Mr Hitler', by George Rodger Redolent in its typography and layout of Picture Post — and carrying, appropriately enough, an introduction by the late Tom Hopkinson — The Blitz consists of photo- graphs from 1940, taken mostly in London, Dover and Coventry. A man carries an armchair from the rubble of his suburban home; a postman, confronted by a pile of bricks, wonders where to post the letters; beaming guests in the Hungaria in Soho sample a gigantic bottle of 1865 brandy, bed down for the night, and are brought breakfast by its urbane-looking owner, clad in a silk dressing-gown; a notice refers anxious relatives to 'Enquiries re Casual- ties on Top Floor, re Deaths on First Floor'. Much tea is drunk, often from mobile canteens, while the Heavy Rescue Squad goes about its business; evacuees board trains at Paddington; mild-looking Home Guards assemble in Whitehall base- ments, uneasily clutching bayoneted rifles. George Rodger went on to cover the war on almost every front, and to become a co-founder of Magnum Photos. As he points out, 48,000 Londoners were killed or wounded in the Blitz — 'and all on account of one bloody little monomaniac'.

George Rodger's photographs of the Blitz are currently being exhibited at the Zelda Gallery, 8 Cecil Court, WC2, until 10 August. Signed original fine prints are avail- able from the gallery.

Previous page

Previous page