WHOSE CHILD, WHOSE FAULT?

More and more children are brought up

without a full family. Alexandra Artley

examines the often painful results

ONE evening this spring I sat in the quiet and austere drawing-room of a house in north London to observe a meeting on fostering, adoption and child welfare. There was a slight stir when a six-day old baby girl unexpectedly arrived in a Moses basket (a portable wicker baby basket with handles). Her new parents were experi- enced adopters who had literally just col- lected her from a hospital. Their emotions were a mixture of joyful possessiveness (`she's ours — the papers just came through!'), relief that the situation had been legally clarified and a rather defensive need to justify the fact they had adopted her at all. They knew that even when it seems to be in the best interests of the baby, there is majestic tragedy in separating a mother and her child.

The baby's mother was a young Irish woman who had been afraid to tell her devout parents that she was pre- gnant. In the ancient way, she had concealed her pregnancy, travelled to England with a friend and given birth to the baby at St Mary's, Paddington. Perhaps thinking that it would be less painful, she was adamant that her daughter should be adopted as soon as possible. The baby had damp black hair, a little rubbery face and the intense pathos of the very, very young. As I held her and gently drank in the damp newborn smell so attractive to maternal women (and rather repulsive to many men) I thought of the mother sitting in the television twilight of a cheap Paddington hotel room with the marks of childbirth still on her and perhaps the emotional reality of what she had done beginning to dawn. Like most mothers who `give up' their children for adoption she would begin to search the faces in every crowd, wondering if that little girl, or that one, or that one with a fleeting look of the family might be her own child. I wondered if she might come to hold her own parents in contempt because in them religious zeal had replaced the spiritual gracefulness and acceptance that draws people closer in- stead of driving them away. As I held her baby close, I also thought how the child would be happy and thriving with her generous new parents until puberty, when the shadow of personal anonymity would cloud her life. Guided by access to birth records at 18 years of age (granted by the Children Act 1975) and perhaps by letters, documents and other scraps of informa- tion, this baby's spirit would not rest until she had found her mother again and after that, possibly her father too.

The spring baby in the Moses basket was one of the increasing number of 'illegiti- mate' children born in Britain. According to the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, there were 126,250 'illegitimate' live births and pre-maritally conceived `legitimate' live births in Britain in 1985 (compared with 64,744 such births in 1970 and 77,372 in 1980). I use the word `illegitimate' with qualification because since the Family Law Reform Act 1987, children in Britain (as in Western Europe as a whole) are now quite simply either `marital' or 'non-marital' and have equal rights before the law.

In her B&B hotel room, or if she is lucky, a very run-down council flat, the teenage mother living on £54 per week maximum, sees on her television screen every morning the new media ideal of single motherhood. This is Anne Di- amond, the breakfast-time presenter of TV-am whose baby will soon be born. This is the Designer Baby whose mother earns £170,000 a year and for whom a special nursery is being built at the studio. Anne Diamond represents the high-flying career woman in her thirties who needs to experi- ence childbirth to complete her success. Like many women in her position, she presumably knows that juggling a career, bringing up a child and sustaining marriage to a man whose own career is demanding requires pretty heroic effort. Dropping marriage is one way of reducing the emo- tional workload. Rigorously tested before birth to ensure high quality, this is the child-as-commodity or fashion accessory.

In between these extremes is the typical- ly courageous single mother I talked to one evening after her four-year-old son had gone to bed. This woman lives in a quiet neat Fifties council flat in King's Cross which she is hoping to buy (`to get my foot on the ladder'). The sitting room had a deep cherry carpet, a three-piece suite and a gilt sun-burst clock on the wall. In the corner with the sound turned down was a television set, her principal adult company and solace.

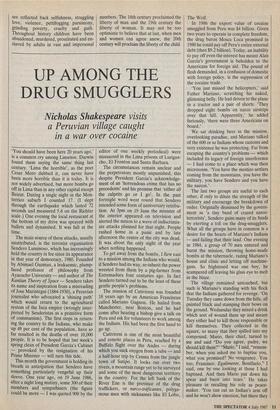

After a long affair this woman wanted to get married but her lover did not. Like many women before and since she may have felt that pregnancy would encourage her lover to final commitment (in all centuries men have been traditionally re- luctant to marry). This woman was 34 at the time and wanted children CI couldn't bear the fact of going through life and having nothing at the end of it'). When she announced her pregnancy, her lover simply Number of one-parent families by marital status in Britain.

1971 1984 Single women 90,000 180,000 Divorced women 120,000 370,000 Separated women 170,000 175,000 Widows 120,000 120,000 Men 70,000 95,000 Total 570,000 940,000 Source: Office of Population Censuses and Surveys vanished but her mother supported her. `He came when the baby was six weeks old and held him. He cried and then walked out and I never saw him since.' I asked whether she would like to marry in the future. 'I don't think I'll meet another man now. I look at a lot of the men going around and I don't think much of them.'

This mother has worked as a legal secretary for the same firm for 13 years and now earns £10,300. After paying basic bills, excluding food, her disposable in- come is £200 per month. Her mother died when her son was one and she greatly misses her emotional encouragement and the small gifts of a five pound note that ease women on low incomes through the month. She said she could change her job to earn more money but she has a good relationship with the firm she works for and depends on them to let her take time off when her son is ill (he has been admitted to hospital twice in four years). Because her life is rather stressful she thinks she is often 'shorter with him than I should be' but 'I always make a point of saying I'm sorry and we make it up before he goes to bed'. Her child is her wealth. 'I just say, keep me going until he's grown up. Let me see him married.'

One of the undercurrents in modern society is an idea that the term 'one-parent family' has now blurred the distinction between marital and non-marital children to the detriment of conventional family life. The unpleasant notion is reasserting itself that only when children are rigorous- ly divided by the cruel stigma of illegitima- cy that 'family life' will miraculously emerge again. What rights a child should have, particularly when they conflict with the ideals of family life has again been brought to the fore in the Middlesbrough cases.

Like most people I would like to think that conventional family life is still the best way to bring up children. To achieve the ideal it means that a man and a woman must have a home, a suitable income and live tolerantly and agreeably together for life to bring up their children with kindness and foresight. But for the beaten or con- stantly betrayed wife, the financially over- whelmed husband or the horribly abused child, the sacred ideal of family life is hellish. These people are members of a family unit but they do not have true family life.

The fact that some married as well as unmarried women have always needed external help to support their children can be seen in the history of the distinguished Edwardian charity, the National Council for the Unmarried Mother and Her Child (renamed the National Council for One- Parent Families in 1973). When it was founded in 1918 by the Oxford economics don Lettice Fisher (wife of the historian H. A. L. Fisher) its full title was the National Council for Unmarried Mother and Her Child and For the Widowed or Deserted Mother in Need. Here, humane people of practical heart recognised that the irres- ponsible, deserting or absent husband was as much a problem in 1918 as he had been in 1850 or 1700.

Today illegitimacy has certainly risen, but by far the greatest number of families headed by lone women are by those who have been divorced. The dramatic figures in the table above show the devastating impact of liberal divorce laws on the ideal of family life in Britain. To these new one-parent families we can now add fami- lies led by men with deserting wives and the women who struggle to bring up families alone because their husbands are away for long periods at sea, in search of work or housing, or in prison. Families have grown into many different forms and when it comes to inflicting financial hardship, emotional stress, health hazards or direct abuse all of them can be said to have sometimes failed the child.

But through the apparent disintegration of the conventional family, children them- selves seem to have been revealed as a new class whose legal rights and real emotional, physical and mental requirements are emerging in greater detail than ever before (even the idea of child suffrage is gently floating through the air).

Powerlessness is a mirror in which socie- ty and government can see its own face. Because children are the most powerless people on earth we can look at them and see reflected back selfishness, struggling love, violence, pettifogging parsimony, grinding poverty, cruelty and guilt. Throughout history children have been abandoned, murdered, prostituted and en- slaved by adults in vast and impersonal numbers. The 18th century proclaimed the liberty of man and the 19th century the liberty of woman. It may not be too optimistic to believe that at last, when men and women can agree anew, the 20th century will proclaim the liberty of the child.

Previous page

Previous page