REVOLTING TASTE

Andrew Gimson on what's behind

German soccer hooliganism (and it's not neo-Nazism)

Berlin JURGEN KLINSMANN is angry about the World Cup. In an interview published on Monday, the German captain said it has 'become very bureaucratic, controlled by functionaries'. Officials order him not to run on to the pitch at the start of a game until the television advertisements have finished. They tell him he earns huge amounts of money from their marketing of the competition, so they expect absolute obedience from him in return. They are not in the slightest bit interested in the possibility that he and others might like to play football in a different spirit.

Mr Klinsmann's anger is shared by many of his countrymen. Being a people much given to self-criticism, they tend to reserve their most bitter comments for their own team. Watching Germany is a 'torture': the players show no flair, no elegance, and are insufferably old. In the interests of fair- ness, and to avoid the very frequent mis- take of underestimating the Germans, we should also say that their team is world- class. It is characterised by fighting spirit, discipline, thoroughness and strength, qualities which enable it to win many of its games without playing inspired football. It is like West Germany's export industries: doubts about whether it could reproduce the brilliant successes of the 1950s have so far proved exaggerated. The team won the World Cup in 1954, and again in 1974, and again in 1990. The industries are also still world-class.

Yet the Germans are not happy. They are in the unenviable state of rich people who feel they only have things to lose. They see a desperate lack of young foot- ballers, and an equally serious shortage of children prepared to take over the family businesses that form the backbone of the economy. They believe they are living on borrowed time, and especially on bor- rowed money. They fear they are heading for a crash of Asian proportions — a fear that I, as a foreign correspondent with a vested interest in bad news, quite often find myself sharing. When the Germans win, either at football or at car-manufac- turing, they only do what they expect of themselves, and they know how transitory success can be; which is one reason why `Yes sir. Although it's always crowded you can still find some room for broken-hearted lovers to cry there in the gloom – but it's strictly no meals in your room and out by ten in the morning.' they have gone on being successful. Their morbid fear of failure saves them from complacency. They change continually, while bewailing their inability to change. Chancellor Helmut Kohl tells them they have achieved great things in the former East Germany in the eight years since reunification: they point instead to all the things which he and they have so far failed to achieve.

This exhausting perfectionism — which is far from being an exclusively German trait — extends to the tiniest details of life. Many a German housewife would be morti- fied to let you into her flat if so much as a speck of dust disfigured the scene. When watering the plants of a couple who had gone on holiday, I took off my shoes before entering their flat and carried a duster so I could immediately mop up any drops of water which splashed onto the perfectly painted windowsills or the immaculate par- quet floor. It was a flat where everything was right, so things could only go wrong. I suspect something went wrong during my stewardship, for I have never been asked to look after the plants again. Flats like this do not exist to be lived in, but to absorb a minimum of four and a half hours' house- work a day and prove to the occupants that they are decent members of society. All of which produces an overwhelming urge in millions of Germans to live in messy flats and rebel against the whole orderly, monied, respectable, timid, inhibited set- up. The most striking cultural urge in Ger- many is towards ghastly bad taste. The country's football hooligans are one mani- festation of this. They will not have the game made respectable.

Herr Klinsmann 'understands their aggression', especially when they are unable to get tickets for Germany's match- es because so many have been allocated to sponsors. 'I have the feeling that football is developing into what tennis used to be,' he said in the interview published on Monday. `A snob sport, an elite sport. Football is getting cut off from its roots.' German hooligans who pick fights with other groups of hooligans are closer to the original spirit of the game than the tightly regulated play- ers inside the stadium. Many of the coun- try's hooligans think that smashing in the unfortunate French policeman's head was going too far: they say this was a breach of the rules of true hooliganism, which only allow attacks on the police when they are preventing a fight with other hooligans. True hooliganism also includes a ban on kicking a man when he is down. (One day hooliganism will be refereed as severely as boxing, nobody will get hurt and young men will invent a more exciting, unofficial alternative.) But 'Spike', a hooligan from Hamburg, took a more robust line in this week's Spiegel magazine: 'I have no problem with the fact that this policeman got a warning. Why didn't he run away? Why did he stand in the way of the entire German mob? He was acting as the henchman of his system, so he must take the consequences.' Spike believes that if Germany meets Holland in the final, nobody will be able to stop the hooligans on either side attacking each other: 'Real hate is involved.' He is right that real hate — and evil — are involved. But much of the hate is directed against the choking idea of respectability. How closely is German football hooliganism bound up, as the French police allege, with right-wing extremism? The ponderous offi- cials in charge of Germany's internal secu- rity service, which operates under the chilling name of the Office for the Protec- tion of the Constitution, deny that genuine neo-Nazis engage much in football hooli- ganism.

It is true that hooligans and neo-Nazis both regard themselves as patriots. But how far does this distinguish them from millions of other Germans who desperate- ly want the national team to win? Patrio- tism is permitted in football, which except when discredited by hooligans — is almost the only respectable way of express- ing nationalism. Neo-Nazism is an even more extreme example than football hooli- ganism of rebellion wielding the weapon of ghastly bad taste. Hatred of foreigners and admiration for Hitler are utterly tasteless sentiments. They offer the easiest of ways to provoke the establishment. Guildo Horn won the right to represent Germany in the Eurovision Song Contest by playing the bad taste card. Instead of struggling to look cool and beautiful, he presented him- self as a sweaty slob. Millions of young Germans found him a release from the pressure to appear as conventionally attractive as possible. Women liked him because he seemed warm and cuddly and genuine, instead of cold and arrogant and power-obsessed. The film Ballermann 6, named after a favourite German bar on Majorca, also did well. It tells the story of two German drunks who start their holi- day by vomiting over the other passengers on the flight to Palma, and then steal a sexy blonde off a rich, uptight man on his yacht. It is the revenge of unkempt Ger- many on the expensively dressed profes- sionals who run the show. When I tell educated Germans that I have seen and enjoyed this film, which is wittier than it sounds, they look at me with deep fore- boding. The German theatre is full of ghastly bad taste. No obscenity is too extreme for the Berlin stage. Bad taste has become established taste.

This is the very craving that German football fans feel. The respectable virtues are all very well, but they cry out for the leaven of freedom, spontaneity and inspi- ration. Well-drilled, commercial football becomes so dull, it must be assaulted by wit or by barbarism. The hooligans have opted for barbarism.

Andrew Gimson is the Daily Telegraph's Getman correspondent.

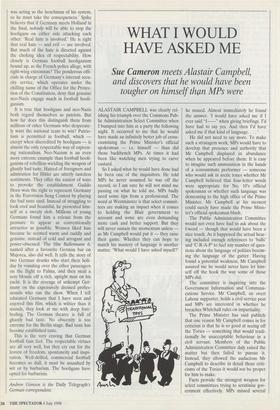

Previous page

Previous page