THE RISE AND FALL OF NEW LABOUR'S EMPIRE

Allan Massie detects an uncanny

resemblance between senior government figures and certain ancient Romans

`I'VE JUST come back from Capri,' the girl said, 'and it occurred to me, at Tiberius's villa, that Peter Mandelson is awfully like Sejanus. What do you think?'

I couldn't — she had a charming voice and a lovely smile — say, 'Don't see it myself.' I said, `Sejanus?' thoughtfully.

Sejanus, I may remark, for the benefit of any Spectator readers whose knowledge of Roman history has never, unlikely as this may seem, advanced further than Shake- speare's (ending, that is, when the asp did its stuff on Cleopatra), was the novus homo whom Tiberius made commander of the Praetorian Guard, and came to rely on utterly, styling him 'the Partner of my Labours'. He exercised almost unlimited power in the emperor's name, and on his behalf, and was chiefly responsible for fomenting the fevered atmosphere which provoked treason trials and a reign of ter- ror. When Tiberius retired to Capri, Sejanus became the necessary link between Rome and the Princeps (still the correct title for the emperor), the channel for all communication.

`Tacitus', I said, 'called Sejanus "a small- town adulterer". That doesn't seem fair to Mandelson.'

`You can't expect every detail to fit,' she said, patiently.

`Tacitus also says that Sejanus "hid behind a modest exterior an unbridled lust for power". And that sounds just like Mandy to me. He adds that .Mandy — I mean Sejanus — was sometimes driven to excess by this lust for power, "but more often to incessant work, which is just as dangerous when it aims at the throne." ' She wrinkled her brow. 'Actually,' she said, 'I feel rather sorry for Mandy.'

`You mean because of what happened to Sejanus?'

`Exactly.'

She shivered, as if in sympathy.

Sejanus, already Tiberius's partner as consul, was expecting to be granted the right of a tribune, which would have enabled him to exercise direct power in Rome, since he could have vetoed any pro- posed law, and initiated any law also. But the letter Tiberius sent to the Senate, instead of announcing his promotion, in fact denounced him, and he was hustled off to execution in the grisly Mamertine prison.

`All the same,' I said, 'it doesn't quite fit, does it? Tony Blair isn't a bit like Tiberius.'

`No,' she said. 'I've been thinking about that too. It's really Gordon Brown who's like Tiberius. "Psychological flaws", you know. Tiberius was eaten up by resent- ment, because Augustus had passed him over, and only made him his heir reluc- tantly when his two grandsons, who were also Tiberius's stepsons, died. Politically, of course, Tiberius was very effective, awfully good on the financial side, certain- ly an "Iron Chancellor". And a control freak. Mommsen — the great German his- torian, in case you've forgotten — says he tried to "regulate the State by means of a strict monitoring of officials and stringent policing", which sounds like our Gordon to me. Oh yes, and he calls him "an unhappy man whom Fate had dealt the heaviest of blows".'

`Like Tony Blair being preferred to him?'

`Precisely. You are catching on.'

`Tiberius', I said, 'was really a Republi- can at heart. The equivalent of Old Labour, I suppose. So, is Tony Blair Augustus?'

`Well,' she said, 'at first I wondered about Caesar, on account of the haircut to hide his baldness — Caesar was awfully sensitive on that subject, you remember. And because of. . . . '

`Someone in the Senate,' I said, 'once denounced Caesar as "every woman's hus- band and every man's wife". Surely you're not suggesting. . . ? '

`No,' she giggled, 'not that, though he has a sort of androgynous appeal. Which Augustus had too, actually, when he was a young man, still named Octavian. And it's Augustus that Tony Blair's like, politically. Look at the way he's sidelined Parliament, just as Augustus sidelined the Senate, while pretending to honour it. You remember that Augustus claimed to have restored the Republic, but really his New Order was creating the Empire — the rule of a single person. And Augustus was care- ful always to present himself as a 'pretty straight kind of guy', while really being absolutely ruthless. And then, I must say' — her ideas • were tumbling over them- selves now — 'Cherie is awfully like his wife Livia. She was very strict, very severe, very sure of herself, and the only person Augustus was afraid of, because she had a stronger character and a much firmer moral sense than he did. I dare say Tony's a bit afraid of Cherie, deep down.'

`Go on,' I said.

`Well then, Roy Jenkins is Cicero, isn't he? Terribly clever and vain and wordy, and always harking back to the time he saved the State — Cicero with the Catiline Conspiracy and Jenkins when he was chan- cellor. And Cicero was always calling for a concordia ordinum, inviting all the boni that's the Great and the Good — to come together and work in harmony, a sort of centre party. And he thought he could use the young Octavian: 'I know intimately the young man's every feeling,' he said; 'there is nothing dearer to him than the Repub- lic.' But, privately it was laudandum adulescentem, ornandum, tollendum — the young man must be praised, decorated, and disposed of. It didn't work out like that of course.'

`No,' I said, 'it was Cicero who was dis- posed of, rather nastily. Poor Lord Jenkins. All right then, what about Maecenas, Augustus's cultural guru? You're surely not casting poor Chris Smith for that role?'

`Maecenas was gay too,' she said, 'crazy for an actor called Rathyllus. But no, I think Mandy doubles for that part.'

`Because of the Dome?'

`Yes, of course. The Ludi Saeculares of 17sc were the new regime's equivalent of the Millennium, and it's my opinion the whole thing was stage-managed by Maece- nas. There was an Etruscan connection and Maecenas belonged to the old Etr- uscan royal family by descent.'

`Like Mandy being Herbert Morrison's grandson?'

`Exactly. You remember, before the Games heralds were sent all over Italy call- ing the country people to Rome, and then on the big day Augustus sacrificed nine lambs and nine kids to the Fates — well, Tony can't do that on account of New Labour's sensitivities, but I dare say they'll find some acceptable substitute, hereditary peers perhaps — and repeated a strange archaic, probably Etruscan prayer to the goddesses who controlled the Destiny of Nations — very New Labour that sounds. Then a blaze of torches turned the silver of the moonlight to a deep red, and hymns were sung to Diana — the People's God- dess, I suppose. It was all terribly camp, just Tony and Mandy's style.'

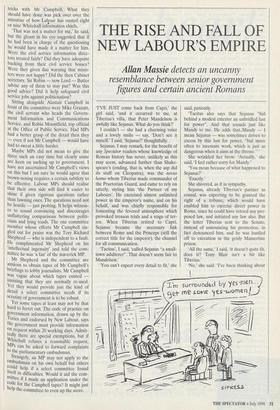

`I'm speechless,' I said. 'Have you found a role for Alastair Campbell? You can't leave him out.'

`That was difficult,' she said. 'I thought of Virgil, who was the sort of press officer for the regime, but all we know of Mr Campbell's literary abilities is that he used to write soft porn, which isn't quite Virgil. I think he comes in later — history can get a bit telescoped when it's repeated — in Claudius's reign. You remember how he was governed by his freedmen — ex-slaves, tabloid hacks as it might be now — espe- cially by two called Narcissus and Pallas. They had no real official position, they couldn't being freedmen, but exercised immense power. Pliny complains in a letter of how a monument to one of them testi- fies to "his insolence and the Senate's ser- vility". Sounds like Mr Campbell to me.'

`Indeed, yes,' I said, 'and what about Nero?'

She frowned.

`Nero comes later. We'll have to wait to see New Labour's Nero. But he'll be along. Now I think you should buy me a bottle of champagne.'

`Absolutely.'

The author's novels include Tiberius and Augustus.

Previous page

Previous page