BOOKS

Feud for thought

Bevis Hillier

STYLISTIC COLD WARS: BETJEMAN VERSUS PEVSNER by Timothy Mowl John Murray, £14.99, pp. 182 John Betjeman once said that the only reason he took jobs was to buy the time to write poetry. It was almost true, but not quite. He also enjoyed the status that some of his posts conferred, had fun decorating his different offices and was entertained by office politics, romances and gossip. But, sooner or later, the gilt began to flake off the gingerbread. He became bored or felt oppressed by authority-figures. More often than not, he chucked his job before his bosses chucked him, flouncing out like Stephen Bayley from the Dome. From 1946 to 1948 he held a salaried post as secretary of the Oxford Preserva- tion Trust. The pay was reasonably good; his office was one of the most historic rooms in the city, the Painted Room in the Cornmarket; and, for once, he was a fish in water. He knew a lot, both about architec- ture in general and Oxford in particular. But the usual happened: becoming jaded with pettifogging paperwork, he swept out with a firework-display tantrum. His dissatisfaction was already becoming clear by November 1946. In that month, the his- torian R. C. K. (later Sir Robert) Ensor, who was one of the trustees, sent a sarcas- tic postcard to another trustee, the Rev J. M. Thompson, Betjeman's former tutor and friend.

When we appointed a secretary [Ensor wrote] prospect was held out of a special campaign which he would conduct to recruit our membership and multiply our funds on a quite outstanding scale. Is anything being done about it?

Thompson made the big mistake of send- ing the postcard on to Betjeman, who flared up and wrote straight off to Ensor in his most acerbic manner. 'As the postcard refers personally to me, I hope you will not mind a personal reply to it.' The burden of the long, cross letter was that fund-raising needed a specialist; he, Betjeman, was overworked and underpaid and was quite prepared to resign. Ensor, who as a histori- an trafficked in rather larger wars, knew how to deal with this uppityness. He replied:

When I wrote to [Thompson], I had no idea of 'pressing for your resignation': if I had, I should not have put it on a postcard . . . It is unusual that the secretary of a society of this kind should entirely disinterest himself in the problems of membership and income.

Because he had this passage of arms with Ensor, and because the Victorian age was the one which most interested him, Betje- man is likely to have read Ensor's brilliant volume in The Oxford History of England, England 1870-1914 (1936). The first chap- ter begins:

During the decade 1870-80 one feature above all others shaped the surface of British politics — the personal duel, continuous save for a period following 1874, between two fig- ures of tremendous stature, Gladstone and Disraeli.

From time to time, history is jazzed up by one of these antithetical pairings, polar opposites — classicism and romanticism, pedantry and arm-chancing, severity and charm: Pitt and Fox, Ingres and Delacroix, Gladstone and Disraeli, Ruskin and Whistler. And now Dr Timothy Mowl has had the bright idea of staging a prize-fight between Nikolaus Pevsner and John Betje- man. He bills it as Stylistic Cold Wars. One wonders what a stylistic hot war would be like: pilasters at dawn?

Though Pevsner seems to have fired the first shots in this war, or series of wars, Bet- jeman was the principal aggressor; in gen- eral, Pevsner either lay doggo or responded with mild irony. In his later years, Betje- man became what the Times called 'a teddy bear to the nation': the avuncular figure in the rumpled suit and battered trilby chugged across our television screens in axed steam trains. But he was a teddy bear with claws. His letter to Ensor is just one example of his touchiness. He was, by and large, a good man, with a deep reservoir of kindness; but those who persist in regard- ing him as a cuddly softie should reread `Slough' and the poem which enraged the National Farmers' Union, beginning, 'We spray the fields and scatter/The poison on the ground.' He absolutely loathed Pevsner, in the same way that he loathed A. R. Gidney, the classics master who had put him down at Marlborough, C. S. Lewis who he felt had slighted him at Oxford, and Farmer John Wheeler, his landlord at Uff- ington, Berkshire, whom he pilloried - again with saeva indignatio — as 'Farmer Whistle' in his poem 'The Dear Old Vil- lage'. He said to me, in the late 1970s, `Why is it that when you have read what Pevsner has to say about a building, you ' never want to look at that building again?' He almost spat the word Pevsner'.

I have never bought into the common opinion that John Betjeman disliked Pevs- ner simply because the German refugee had a categorising, 'Teutonic' approach to buildings, the antithesis of his own, more humane, response. That did come into it, certainly: Betjeman was always as much interested in the shellfish as the shell - wanted to record or guess who had lived or did live in any given house. A toothbrush airing on a north Oxford window-sill was a clue to donnish inhabitants. In his guides he would give you the lowdown on baronets, literary associations, even ghost stories. Pevsner, by contrast, stuck almost exclusively to the architecture, in the moralistic terms of what used to be called `beautility' — fitness of the structure for its function.

The two approaches were delightfully parodied in a Punch feature in 1954 (not picked up by Mowl) written by Peter Clarke, whom I knew when he was compa- ny secretary of the Times. (In the lunch- hours, at the Baynard Castle pub at Blackfriars, he would do side-splitting imi- tations of William Rees-Mogg's editorial conferences.) The Pevsner send-up went like this: Smoggy Hall. C.18. Offices of Northmet and British Restaurant. 1-2-3-hop 1-2-3 window arrangement. Characteristic double-hollow- chamfered waterspout. Not specially nice. Slaughterhouse (Waterhouse?). Beefy, ham- fisted .. .

Then the Betjeman parody: From The Last Rows of Somers Town (with 100 drawings in pen and wash of Non- conformist chapels in stormy weather).

`Ah Smoggy Fields! Victims of Progress and the Welfare State! Yet your ragged elms and stuccoed railway station (Sancton Wood, 1848, but ruined by British Railways of course) recall to me a bright morning on which I set out with my great-uncle to see the opening of the White City. What art-nouveau panes may not still lurk in your Ladies' Wait- ing Room? What sets of tennis may not be played out in the dusk on your Municipal Courts? What etc.? Ah! etc. etc.'

From the ferocity of Betjeman's animus against Pevsner, I have always felt sure that some real or imagined slight was at the root of the antagonism. Mowl suggests a possible casus belli. When the architect and designer C. F. A. Voysey died in 1941, Bet- jeman, who had known him well, sent the Architectural Review an article about him.

His article was not used [Mowl writes]. Niko- laus Pevsner, the enemy alien recently released from internment, supplied the mag- azine's tribute and farewell. There is no need to look any further for the source of Betje- man's subsequent dislike of his rival, not that he would ever have favoured a foreign inter- loper in a field he considered his own.

But I think there is a need to look fur- ther. For a start, though the incident might not have endeared Pevsner to him, Betje- man is more likely to have blamed the Review's editor, J. M. Richards, for his being usurped. More significantly, as Mowl himself observes, 'open warfare' between the two men did not break out until 1952, more than ten years after the business of the Voysey tribute. As Mowl also points out, Betjeman may well have taken person- ally a passage in Pevsner's Outline of Euro- pean Architecture (1942):

America is prouder of her achievements than Britain, or at least more attached to them . In England what attention is paid to Victori- an buildings and design is still, with a very few exceptions, of the whimsical variety.

Also in 1942, Pevsner dismissed as `genial overstatement' an article Betjeman had written in 1939 entitled The Seeing Eye or How to Like Everything'. There was some natural competitiveness over the rival guidebooks the two men edited. Then, in 1952, came the grand rift. A. L. Rowse told me he thought it was Pevsner's attack on Sir Ninian Comper, an architect Betjeman very publicly admired, that caused Betje- man to take against Pevsner so implacably. Mowl would seem to agree. In London Vol- ume 2 (1952), Pevsner attacked Comper's St Cyprian, Marylebone, adding:

There is no reason for the excesses of praise lavished on Comper's church furnishings by those who confound aesthetic with religious emotions.

But then how to account for the fact that an early derogatory comment about Pevs- ner by Betjeman appeared in Time & Tide (of which the poet was then literary editor) in January 1952 — when Pevsner's book appeared later that year? Also in 1952, Betjeman referred scathingly to 'Herr Professor-Doktors' in the preface to his prose collection, First and Last Loves. A solution to the mystery may be an inter- office memorandum which I found in the BBC archives at Caversham, near Reading, to the effect that Mr Betjeman wished never again to appear on a discussion pro- gramme with Professor Pevsner. Had Pevs- ner, in a broadcast with Betjeman, said something which the poet took as unforgiv- ably wounding?

From 1953, Betjeman went in for contin- ual Pevsner-baiting. On 3 July he wrote a savage attack on him and all his works in the Times Literal)? Supplement. On 18 July (as Mowl again records) he refused to let Pevsner's friend Alec Clifton-Taylor defend the professor in Time & Tide. Pevs- ner seldom bothered to retaliate, though he did drily comment that he understood that Betjeman had been 'an undergraduate at Oxford' — an oblique sneer at his failure to take a degree.

Timothy Mowl has found himself a sub- ject which is genuinely new and he exploits it with vivacity. I think most people will enjoy the book on the level of a sophisticat- ed Punch and Judy show. He advances some interesting new theories, for example the claim that Edith Olivier influenced Bet- jeman's guidebook style. But the book is flawed in three ways. First, as it is a pio- neer study it should have been footnoted. The absence of reference notes means that any future scholar discussing the Betjeman- Pevsner relationship will have to trawl through all the books and papers for infor- mation Mowl could have put at our finger- tips. It is a piece of academic bad manners.

Second, Mowl's homework is patchy. He misses not only Peter Clarke's parody of the Pevsner and Betjeman guidebooks but also his wicked poem about the two men, `Poet and Pedant', published in Punch in November 1955 — by which time the rather one-sided Betjeman-Pevsner feud was public knowledge. A sample: POET: A POET-part-Victorian part-Topographer — that's me! (Who was it tipped you Norman Shaw in Nineteen Thirty-three?) Of gas-lit Halls and Old Canals I reverently sing, But when Big-Chief-I-Spy comes round I curse like anything.

0o-oh!

PEDANT: A crafty Art Historian of Continental fame, I'll creep up on this Amateur and stop his little game!

With transatlantic thoroughness I'll note down all he's missed.

Each British Brick from Norm. to Vic.

you'll find upon my list!

(Aside: Ah-h-h!) The omission of this poem, though regrettable, merely deprives Mowl's read- ers of some knockabout fun. More serious is his failure adequately to deal with the three great conservation battles of the early 1960s in which both Betjeman and Pevsner were involved with the newly founded Vic- torian Society — over the Euston Arch (lost), the Coal Exchange (lost) and Bed- ford Park (triumphantly won). He gives only one sentence apiece to the first two, and although, en passant, he mentions Bed- ford Park as having been partly built by Norman Shaw, he has nothing about the battle to save it.

The first person to express concern about the Euston Arch was Woodrow Wyatt MP in February 1960. ('We thought we'd confound their knavish tricks,' he told me.) On 19 April the Times published a strong letter from Pevsner deploring the threat to the arch. I suspect — it is only a hunch — that Pevsner's intervention may have caused Betjeman to hold back for a while, though eventually he did campaign against the threatened destruction, in print and on television. He held back long enough for his friend John Summerson to put the boot in, disparaging the arch in a long, sly article in the Times (11 June 1960). No doubt Summerson's views influ- enced Sir William Haley in his writing the infamous Times editorial ('Not worth sav- ing', 17 October 1961) which in turn encouraged Harold Macmillan to reject demands that the arch be saved.

With the Coal Exchange, as Mowl points out in his single sentence on the subject, it was Betjeman, not Pevsner, who made the running — though this was exactly the sort of industrial architecture that Pevsner extolled. But Pevsner was not silent on the topic, as you might conclude from Mowl. On 8 February 1961 he, Betjeman and the bombastic television archaeologist Sir Mor- timer Wheeler held a press conference to appeal for the Exchange's preservation. Pevsner, the Times reported on 9 February, `agreed with Mr Betjeman' that the undistinguished back of the Custom House could be demolished to make room for the road which was the excuse for razing the Exchange.

So in both these campaigns Betjeman and Pevsner, if they did not actually link arms, were on the same side. Even more was that the case with Bedford Park, where what was threatened was the wholesale demolition of a remarkable area of Lon- don, architecturally all of a piece. In my John Betjeman: A Life in Pictures (1984) is reproduced in colour a painting by Tom Greeves and Peter Clarke of 'The Battle of Bedford Park'. It shows Pevsner, in mortar- board and gown, and Betjeman, with a straw hat, side by side, leading their troops against a vandal party led, yet again, by Summerson, who had given the ornament- ed Bedford Park another of his frigid nega- tive verdicts.

My third reservation about this book concerns its author. I have reviewed two other books by Mowl, his biographies of Horace Walpole and William Beckford. There were good things to say about each; but this new book confirms the impression I have of him: it is like listening to a clever but rather choleric schoolmaster, much given to riding hobby-horses. He is never dull but too often opinionated. He obtrudes himself in a slightly absurd way. Of Pevsner's views on the neo-Norman style (the subject of Mowl's doctoral thesis) he writes with gracious condescension: `Though I might disagree with him, there were times when his judgment was sound . . ' Bully for you, Pevvers. A man who can write thus of a Pevsner garlanded with degrees naturally treats Betjeman de haut en bas. He comments on his 'fatuous waste of time at Oxford' — meaning, pre- sumably, that Betjeman did not take a degree but 'wasted' his time making friends for life with such frivolous nonentities as Kenneth Clark, W. H. Auden, John Sparrow and Maurice Bowra.

Mowl is muddled in his attitude to Betje- man and Pevsner. On the one hand, Pevs- ner, like himself, has the academic credentials, so Mowl respects him, and it is noticeable that while he intermittently refers to both men by their first names, Pevsner is usually called `Pevsner', but Betjeman is much more often 'John'. On the other hand, Mowl was influenced and impressed, as a young man, by Dr David Watkin's attack on Pevsner in his Morality and Architecure (1977) — a book I remem- ber Betjeman praising to the skies. Watkin condemned Pevsner for his doctrinaire pro- Bauhaus views; and you feel that the swashbuckling Mowl is on Watkin's side in this — indeed, Watkin 'was kind enough to entertain me in Albany with his forthright views on both Betjeman and Pevsner'. So there is a conflict here. It is never quite resolved, but Mowl is more consistently pro-Pevsner than pro-Betjeman. At times he is utterly unfair to Betjeman. One instance is this statement, relating to a Bet- jeman article of 1933:

It was with Euston that he made misjudg- ments which were to count against him in future years where the Victorian Society .. . was concerned. When they came to appoint a new chairman it would be German Nikolaus whom they chose, not English John ...`For many years now,' he noted, with no sign of anger or protest, 'there have been rumours about the demolition of its Great Arch.' . . . Back in 1933 John was airily unconcerned with such relics. What was needed was a clean sweep of Euston's clutter . . . If as a result 'the Great Hall must go, then that is that; and if the arch must be demolished, then that is that too'.

What Betjeman also wrote of the Euston Arch in 1933 — prophetically — was, 'If vandals ever pulled down this lovely piece of architecture, it would seem as though the British Constitution had collapsed.' So surely, in the passage selectively quoted by Mowl, Betjeman was being ironic about the need for demolition, just as he was, later on, about the need to pull down Westmin- ster Abbey to ease traffic congestion. Mowl is like those who put Daniel Defoe in the pillory for his The Shortest Way with Dis- senters in which he ironically urged severe penalties against dissenters (of whom he was one). And this misunderstanding makes one realise where Mowl is most deficient: in a sense of humour. People lacking that faculty never did see the point of John Betjeman. As for the idea that the Victorian Society rejected Betjeman as chairman in the late 1950s for something he wrote about Euston some 25 years earli- er, I cannot believe there is a scrap of evi- dence for that. (This is where we need those footnotes, Dr M.) Again, when he writes of Betjeman's friend P. Morton Shand, 'He was such a lustful man, four times married, that he could literally make the buildings he took up sound sexy', I take leave to doubt that Mowl has fully and fairly investigated Shand's private life leaving aside the bizarre non-sequitur of the sentence.

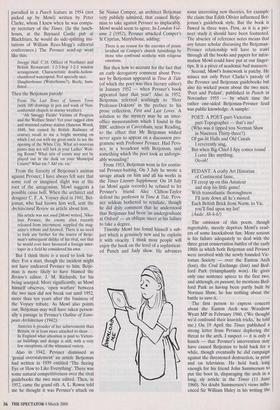

The whole apparatus of the book is cun- ningly stage-managed to counterpoise Bet- jeman and Pevsner, from the jacket (admirably designed by the publishing house's chairman, John R. Murray), in which `Betjeman' appears in ornate lettering, Pevsner' in austere, to the photographs of the men — Pevsner worried-looking amid piles of his guide- books, Betjeman shrieking with laughter in a deck-chair. And then there are the pic- tures of their two gravestones — Betje- man's covered in joyous flourishes and curlicues, Pevsner's with chastely chiselled characters. One feels that the three conser- vation campaigns of the early 1960s may have been played down because they do not fit in with the counterpoised Punch and Judy images Mowl wants to present. When he writes of the curious parallelism between the men, it is mainly to superficial similarities that he points — their foreign names, their both settling in Berkshire, their being knighted in the same year, their both contracting Parkinson's disease. Near the end of his introduction, Mowl writes:

Architecture has so much capital, monetary and emotional, invested in it that few of us can afford to be entirely truthful. Mistrust me as I mistrust my two protagonists.

We do, sir, we do.

Bevis Hillier's John Betjeman: The Years of Fame, 1934-84, the second and final volume of his authorised biography of the pdet, will be published by John Murray in autumn 2001.

Previous page

Previous page