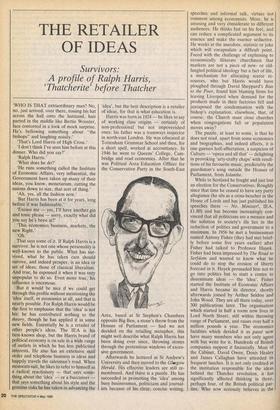

THE RETAILER OF IDEAS

Survivors: `Thatcherite' before Thatcher

'WHO IS THAT extraordinary man? No, no, just arrived, over there, tossing his hat across the hall onto the hatstand, hair parted in the middle like Bertie Wooster, face contorted in a look of mock surprise. He's bellowing something about "the bishops" and laughing noisily.'

'That's Lord Harris of High Cross.'

'I don't think I've seen him before at this dinner. Who did you say?'

'Ralph Harris.'

'What does he do?'

'He runs something called the Institute of Economic Affairs, very influential, the Government have taken up many of their ideas, you know, monetarism, cutting the unions down to size, that sort of thing.'

`Ah, yes, all the fashion now.'

'But Harris has been at it for years, long before it was fashionable.'

'Excuse me — yes, I'll have another gin and tonic please — sorry, exactly what did you say he's been at?'

'This economics 'business, markets, the new Right.'

'Oh.'

That says some of it. If Ralph Harris is a survivor, he is not one whose personality is well-known to the public. What has sur- vived, what he has taken care should survive, and indeed prosper, is an idea or set of ideas; those of classical liberalism. And true, he espoused it when it was very unpopular to do so. Even more true, his influence is enormous.

But it would be nice if we could get through this profile without mentioning the 'idea' itself, or economics at all, and that is nearly possible. For Ralph Harris would be the first to emphasise that the 'idea' is not his: he has contributed nothing to the theory, though he has applied it in some new fields. Essentially he is a retailer of other people's ideas. The IEA is his best-known shop, but the Harris brand of political economy is on sale in a wide range of outlets in which he has less publicised interests. He also has an extensive mail order and telephone business in ideas and happily travels the salesman's road. When moments suit, he likes to refer to himself as a radical reactionary — that says some- thing about the 'idea' — or a buccaneer — that says something about his style and the genuine risks he has taken in advancing the 'idea', but the best description is a retailer of ideas, for that is what education is.

Harris was born in 1924— he likes to say of working class origins — certainly of non-professional but not impoverished ones: his father was a tramways inspector in north-east London. He was educated at Tottenham Grammar School and then, for a short spell, worked at accountancy. In 1946 he went to Queens' College, Cam- bridge and read economics. After that he was Political Area Education Officer for the Conservative Party in the South-East Area, based at St Stephen's Chambers opposite Big Ben, a stone's throw from the Houses of Parliament — had we not decided on the retailing metaphor, this might well describe what Ralph Harris has been doing ever since, throwing stonps through the pretentious windows of exces- sive government.

Afterwards he lectured at St Andrew's University and then moved to the Glasgow Herald. His effective leaders are still re- membered. And there is a puzzle. He has succeeded in promoting the 'idea' among busy businessmen, politicians and journal- ists because of his clear, concise writing, speeches and informal talk, virtues not common among economists. More, he is amusing and very cbnsiderate to different audiences. He thinks fast on his feet, and can reduce a complicated argument to its essence and make the essence seductive. lie works at the anecdote, statistic or joke which will encapsulate a difficult point. Faced with the challenge of explaining to economically illiterate churchmen that markets are not a piece of new- or old- fangled political ideology but a fact of life, a mechanism for allocating scarce re- sources, who but Harris would have ploughed through David Sheppard's Bias to the Poor, found him blaming firms for leaving Liverpool when demand for the products made in their factories fell and juxtaposed the condemnation with the bishop's explanation, elsewhere, that, of course, the Church must close churches when congregations fall or population moves away?

The puzzle, at least to some, is that he does not read, apart from some economics and biographies, and indeed affects, it is one guesses half-affectation, a suspicion of Culture — 'opera and all that' — delighting in provoking 'arty-crafty chaps' with rendi- tions of his favourite music, predictably the guardsman's song outside the Houses of Parliament, from Iolanthe.

While in Scotland he fought and just lost an election for the Conservatives. Roughly since that time he ceased to have any party allegiance (he sits as a cross-bencher in the House of Lords and has just published his speeches there — No, Minister!, IEA , £1.80) and has become increasingly con- vinced that all politicians are a menace and the solution to society's ills lies in the reduction of politics and government to a minimum. In 1956 he met a businessman named Antony Fisher (they had met brief- ly before some five years earlier) after Fisher had talked to Professor Hayek. Fisher had been impressed by The Road to Serfdom and wanted to know what he could do to stop the erosion of liberty forecast in it. Hayek persuaded him not to go into politics but to start a centre to disseminate ideas — the 'idea'. Fisher started the Institute of Economic Affairs and Harris became its director, shortly afterwards joined by Arthur Seldon and John Wood. They are all there today, over 300 publications later. The organisation which started in half a room now lives in

Lord North Street, still within throwing range of Parliament, and raises over half a million pounds a year. The economics faculties which derided it as passé now have many members who not only agree with but write for it. Hundreds of British companies support it financially. Most of the Cabinet, David Owen, Denis Healey and James Callaghan have attended its frequent lunches. It is not only credited as the institution responsible for the ideas behind the Thatcher revolution, it has significantly affected thinking in three, perhaps four, of the British political par- ties. Who now seriously believes in the automatic advantages of ubiquitous nationalisation, who in the unmitigated good of state planning?

The achievement at the LEA is easy to describe: running and funding an institu- tion corfimitted to the publication of highly influential academic economic treatises for nearly 30 years with no state money at all. There is simply no other organisation or person that has done this. It was not planned or done systematically. One of the great joys of the LEA is that it proves that the inspired conspiracies of two or three men can move mass societies. For the IEA is run on a huge web of personal contacts, initiated and consolidated by Ralph Harris and by luck. I don't think Harris has ever advertised for a senior post at the Institute. He is just lucky enough to meet John Wood and Arthur Se!don, the one re- sponsible for much of the quiet efficiency of the IEA's organisation and crucial hos- pitality, the other for finding, commission- ing and editing — and oh what splendid editing — the Institute's economist authors and publications, its lifeblood. Both are polished economic writers on their own account.

But the LEA is only the brand name shop. Harris started Churchill Press with Rhodes Boyson. He set up the Wincott Foundation with its press awards, lectures and research grants. At the risk of antago- nising several who also played a significant part, one can say that it is well known that the University of Buckingham would not have happened without Ralph Harris. Others have the ideas. Others provide the money. Harris makes it happen. He deliv- ers; the retailer again. In some organisa- tions, such as the Ross McWhirter Founda- tion, he is the crucial, tireless supporter: others such as the Political Economy club or the Mont Pelerin Society, that interna- tional mafia of free market economists, he finds at a low point in their history and reinvigorates. Others he is simply hospit- able towards. The Centre for Research into Communist Economies and the Social Affairs Unit live at 2 Lord North Street. Many more organisations meet there. Yet others he stealthily in- and per-vades: since his arrival in the House of Lords, several members have simultaneously discovered an appetite for repealing legislation — the truck acts (governing payment of wages in cash), restrictions on shop opening hours and the licensing laws.

There is a price to pay for all this: little time or energy for leisure and home. Ralph Harris is not much interested in posses- sions apart from antiques and hats, or in leisure pursuits except conjuring (he was a member of the Magic Circle) and walking his cats across the golf course. There are other prices: behind the smile, toughness, of course, but also a sternness. For Lord Harris is no libertarian. A Christian with little theological but much moral interest, his morality is of a traditional English Protestant kind, more sin and sorrowful Cross than joy in Resurrection.

Does the 'idea' matter? In different circumstances could Ralph Harris have been a promoter, a retailer of second-hand Fabian, Keynesian or Marxist ideas? I think not: though he himself would stress that he is an economist, the inspiration which drives him is moral and the sort of economics he espouses suits well his par- ticular moral outlook. Even Ralph Harris's opponents, those who find his morality and economics distasteful and his influence perturbing, acknowledge his courtesy to- wards them and his beneficial effect on public debate: many have improved their own arguments prodded by competition with his. And none would deny his unique achievement as an ideological entrep- reneur, a retailer of ideas.

Had the gin and tonic guest pursued his inquiry further, he would, no doubt, have found that the funds that made possible the charity dinner and the two gin and tonics had been raised by that 'extraordinary man'.

Previous page

Previous page