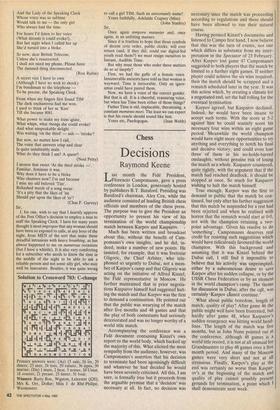

Chess

Decisions

Raymond Keene

Last month the Fide President, Florencio Campomanes, gave a press conference in London, generously hosted by publishers B.T. Batsford. Presiding was Batsford's chairman, Alex Cox, while the audience consisted of leading British chess officials and members of the chess press. The purpose was to give the President an opportunity to present his view of his termination of the world championship match between Karpov and Kasparov.

Much has been written and broadcast about this, without the benefit of Cam- pomanes's own insights, and he did, in- deed, make a number of new points. He insisted, for example, that it was Svetozar Gligoric, the Chief Arbiter, who tele- phoned so urgently to Dubai, not a mem- ber of Karpov's camp and that Gligoric was acting on the initiative of Alfred Kinzel, the Fide representative in Moscow. He further maintained that in prior negotia- tions Kasparov himself had suggested halt- ing the match and that Karpov was the first to demand a continuation. He pointed out that the public was wearying of the match after five months and 48 games and that the play of both contestants had seriously deteriorated and was no longer worthy of a world title match.

Accompanying the conference was a Fide document containing Kinzel's own report to the world body, which backed up' the majority of this. What elicited the most sympathy from the audience, however, was Campomanes's assertion that his decision to terminate had been agonisingly difficult and whatever he had decided he would have been severely criticised. All this, I am sure, is formally true but it proceeds from the arguable premise that a 'decision' was necessary at all. In fact, no decision was

necessary, since the match was proceeding according to regulations and these should have been allowed to run their natural course.

Having perused Kinzel's documents and listened to Campo first hand, I now believe that this was the turn of events, not one

which differs in substance from my inter- pretation in the Spectator of 23 February.

After Karpov lost game 47 Campomanes suggested to both players that the match be limited to a further eight games. If neither player could achieve the six wins required, then the match should be scrapped and a rematch scheduled later in the year. It was this action which, by creating a climate for a negotiated end, set the ball rolling for the eventual termination.

Karpov agreed, but Kasparov declined. Indeed, he would have been insane to accept such terms. With the score at 5-2 against him he could scarcely score his necessary four wins within an eight game period. Meanwhile the world champion would have eight more opportunities to try anything and everything to notch his final and decisive victory, and could even lose three of them in his no-holds-barred onslaughts, without genuine risk of losing the match as a whole. Kasparov countered, quite rightly, with the argument that if the match had reached deadlock, it should be stopped at once. So much for Kasparov wishing to halt the match himself.

True enough, Karpov was the first to demand in public that the match be con- tinued, but only after his further suggestion that this match be suspended for a rest had been rejected and when he realised with horror that the rematch would start at 0-0, not with the champion retaining a two- point advantage. Given his resolve to do :something', Campomanes deserves real credit for resisting such suggestions which would have ridiculously favoured the world champion. With this background and assuming that it was Kinzel behind the Dubai call, I still find it impossible to believe that his activity was unprompted, either by a subconscious desire to save Karpov after his sudden collapse, or by the USSR Chess Federation or by an element in the world champion's camp. The theme for discussion in Dubai, after the call, was certainly '.Karpov cannot continue.'

What about public boredom, length of match, quality of play? After game 46 the public might well have been frustrated, but hardly after game 48, when Kasparov's sudden resurgence was hitting world head- lines. The length of the match was five months, but as John Nunn pointed out at the conference, although 48 games is a world title record, it is not at all unusual for Grandmasters to play 48 games over a five month period. And many of the Moscow games were very short and not at all strenuous. Finally, Karpov's play at the end was certainly no worse than Kaspat- ov's at the beginning of the match and quality of play cannot possibly present grounds for termination, a point which I shall demonstrate next week.

Previous page

Previous page