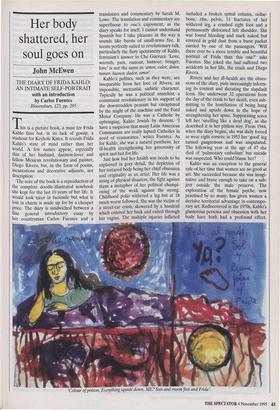

Her body shattered, her soul goes on

John McEwen

THE DIARY OF FRIDA KAHLO: AN INTIMATE SELF-PORTRAIT with an introduction by Carlos Fuentes Bloomsbury, £25, pp. 295 This is a picture book, a must for Frida Kahlo fans but, in its lack of gossip, a washout for Keyhole Kates. It reveals Frida Kahlo's state of mind rather than her world. A few names appear, especially that of her husband, daemon-lover and fellow Mexican revolutionary and painter, Diego Rivera, but, in the form of poems, incantations and decorative adjuncts, not description.

The core of the book is a reproduction of the complete doodle-illustrated notebook she kept for the last 10 years of her life. It would look nicer in facsimile but what is lost in charm is made up for by a cheaper price. The diary is sandwiched between a fine general introductory essay by her countryman Carlos Fuentes and a translation and commentary by Sarah M. Lowe. The translation and commentary are superfluous to one's enjoyment, as the diary speaks for itself. I cannot understand Spanish but I take pleasure in the way it sounds like bursts of small-arms fire. It seems perfectly suited to revolutionary talk, particularly the fiery spontaneity of Kahlo, feminism's answer to Che Guevara. 'Love, warmth, pain, rumour, humour, bringer, love' is not the same as `amor, calor, dolor, rumor, humor, dador, amor'.

Kahlo's politics, such as they were, are inseparable from her love of Rivera, an impossible, mercurial, sadistic character. Typically he was a political anarchist, a communist revolutionary in his support of the downtrodden peasant but enraptured by the might of the machine and the Ford Motor Company. He was a Catholic by upbringing, Kahlo Jewish by descent. 'I have a suspicion that many Latin American Communists are really lapsed Catholics in need of reassurance,' writes Fuentes. As for Kalilo, she was a natural pantheist, her ill-health strengthening her generosity of spirit and lust for life. Just how bad her health was needs to be explained in gory detail, the depiction of her tortured body being her chief obsession and originality as an artist. Her life was a string of physical disasters, the fight against them a metaphor of her political champi- oning of the weak against the strong. Childhood polio withered a leg but at 18 much worse followed. She was the victim of a street-car crash, skewered by a handrail which entered her back and exited through her vagina. The multiple injuries inflicted included a broken spinal column, collar- bone, ribs, pelvis, 11 fractures of her withered leg, a crushed right foot and a permanently dislocated left shoulder. She was found bleeding and stark naked but covered in gold dust from a burst packet carried by one of the passengers. 'Will there ever be a more terrible and beautiful portrait of Frida than this one?' asks Fuentes. She joked she had suffered two accidents in her life, the crash and Diego Rivera.

Rivera and her ill-health are the obses- sions of the diary, pain increasingly inform- ing its content and dictating the slapdash form. She underwent 32 operations from the day of the crash to her death, even sub- mitting to the humiliation of being hung naked and upside down in the hope of strengthening her spine. Suppurating sores left her 'smelling like a dead dog', as she described it in her pitiless way. From 1944, when the diary begins, she was daily forced to wear eight corsets; in 1953 her 'good' leg turned gangrenous and was amputated. The following year at the age of 47 she died of 'pulmonary embolism' but suicide was suspected. Who could blame her?

Kahlo was an exception to the general rule of her time that women are no good at art. She succeeded because she was imagi- native and brave enough to take on a sub- ject outside the male preserve. The exploration of the female psyche, now practised by so many, has given women a decisive territorial advantage in contempo- rary art. Rediscovered in the 1970s, Kahlo's glamorous persona and obsession with her body have both had a profound effect.

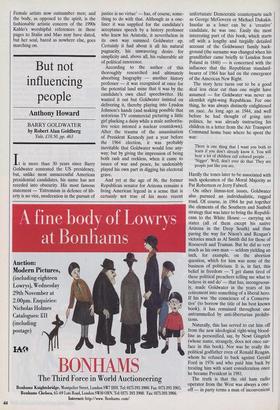

Colour of poison. Everything upside down. ME? Sun and moon feet and Frida'. Female artists now outnumber men; and the body, as opposed to the spirit, is the fashionable artistic concern of the 1990s Kahlo's worshipful references in these pages to Stalin and Mao may have dated, but her soul, bared as nowhere else, goes marching on.

Previous page

Previous page