ARTS

Comedy

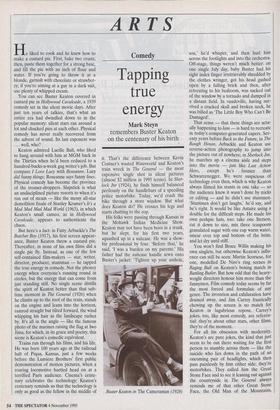

Tapping true energy

Mark Steyn remembers Buster Keaton on the centenary of his birth

He liked to cook and he knew how to make a custard pie. First, bake two crusts; then, paste them together for a strong base, and fill the pie with an inch of flour and water. If you're going to throw it at a blonde, garnish with chocolate or strawber- ry; if you're aiming at a guy in a dark suit, use plenty of whipped cream.

You can see Buster Keaton covered in custard pie in Hollywood Cavalcade, a 1939 comedy set in the silent movie days. After just ten years of talkies, that's what an entire era had dwindled down to in the popular memory: silent stars ran around a lot and chucked pies at each other. Physical comedy has never really recovered from the advent of sound. Its last exponent was . well, who?

Keaton admired Lucille Ball, who liked to hang around with him at MGM back in the Thirties when he'd been reduced to a hundred-bucks-a-week gag writer's job. But compare I Love Lucy with Roseanne. Lucy did funny things; Roseanne says funny lines. Physical comedy has become the province of the trouser-droppers. Slapstick is what an undisciplined picture resorts to when it's run out of steam — like the messy all-star demolition finale of Stanley Kramer's It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963), in which Keaton's small cameo, as in Hollywood Cavalcade, appears to authenticate the chaos.

But here's a fact: in Fatty Arbuckle's The Butcher Boy (1917), his first screen appear- ance, Buster Keaton threw a custard pie. Thereafter, in none of his own films did a single pie fly. Instead, as one of the few self-contained film-makers — star, writer, director, producer, stuntman — he tapped the true energy in comedy. Not the phoney energy when everyone's running round in circles, but the energy that can come from just standing still. No single scene distills the spirit of Keaton better than that sub- lime moment in The General (1926) when he climbs up to the roof of the train, stands on the engine and leans into the horizon, ramrod straight but tilted forward, the wind whipping his hair as the landscape rushes by. It's all in the angle — like the famous photo of the marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, for which, in its grace and poetry, this scene is Keaton's comedic equivalent.

Trains run through his films, and his life. He was born 100 years ago at the railroad halt of Piqua, Kansas, just a few weeks before the Lumiere Brothers' first public demonstration of motion pictures, when a roaring locomotive hurtled head on at a terrified Paris audience. Cinema's cente- nary celebrates the technology; Keaton's centenary reminds us that the technology is only as good as the fellow in the middle of it. That's the difference between Kevin Costner's wasted Waterworld and Keaton's train wreck in The General — the most expensive single shot in silent pictures (almost $2 million in 1995 terms). In Sher- lock Jnr (1924), he finds himself balanced perilously on the handlebars of a speeding police motorbike. Today, we'd crash the bike through a store window. But what does Keaton do? He crosses his legs and starts chatting to the cop.

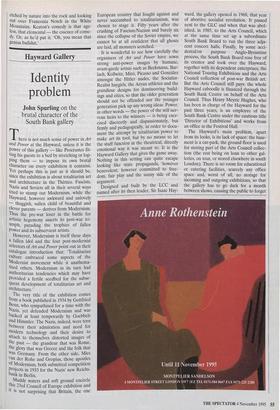

His folks were passing through Kansas in the Mohawk Indian Medicine Show. Keaton may not have been born in a trunk, but he slept, for his first two years, squashed up in a suitcase. He was a show- biz professional by four. 'Before that,' he said, 'I was a burden on my parents.' His father had the suitcase handle sewn onto Buster's jacket: 'Tighten up your asshole, Buster Keaton in The Cameraman (1928) son,' he'd whisper, and then hurl him across the footlights and into the orchestra. Off-stage, things weren't much better: on one single July day, baby Buster had his right index finger irretrievably shredded by the clothes wringer, got his head gashed open by a falling brick and then, after retreating to his bedroom, was sucked out of the window by a tornado and dumped in a distant field. In vaudeville, having sur- vived a cracked skull and broken neck, he was billed as 'The Little Boy Who Can't Be Damaged'.

That sense — that these things are actu- ally happening to him — is hard to recreate in today's computer-generated capers. Sev- enty years before Back to the Future, in The Rough House, Arbuckle and Keaton use reverse-action photography to jump into the picture out of nowhere; in Sherlock Jnr, he marches up a cinema aisle and steps into the movie — just like Last Action Hero, except he's funnier than Schwarzenegger. We were suspicious of technology even then, which is why Keaton always filmed his stunts in one take — so the audience knew it wasn't done by tricks or editing — and he didn't use stuntmen. `Stuntmen don't get laughs,' he'd say, and he's right. It would be like Astaire using a double for the difficult steps. He made his own porkpie hats, too: take one Stetson, cut it down to size, mix three teaspoons granulated sugar with one cup warm water, smear over top and bottom of the brim, and let dry until stiff.

You won't find Bruce Willis making his own singlets, but otherwise Keaton's influ- ence can still be seen: Martin Scorsese, for one, modelled De Niro's ring scenes in Raging Bull on Keaton's boxing match in Battling Butler. But how odd that the heavy- weight directors honour him more than the funnymen. Film comedy today seems by far the most forced and formulaic of any genre. The invention and exhilaration have drained away, and Jim Carrey frantically chewing up the screen is no match for Keaton in lugubrious repose. Carrey's jokes, too, like most comedy, are referen- tial: they're about other stars, other films, they're of the moment.

For all his obsession with modernity, Keaton's are pure jokes, the kind that just seem to be out there waiting for the first person to stumble across them — like the suicide who lies down in the path of an oncoming pair of headlights, which then pass painlessly by him either side: they're motorbikes. They called him the Great Stone Face and to see it leaning out against the countryside in The General always reminds me of that other Great Stone Face, the Old Man of the Mountains,

etched by nature into the rock and looking out over Franconia Notch in the White Mountains. Keaton's comedy is that age- less, that elemental — the essence of come- dy. Or, as he'd put it, 'Oh, you mean that genius bullshit.'

Previous page

Previous page