HAULIER THAN THOU

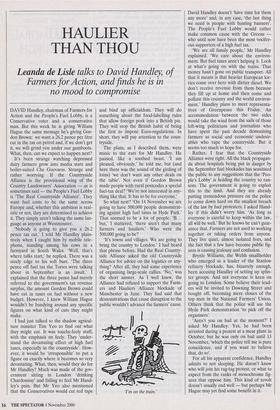

Leanda de Lisle talks to David Handley, of

Farmers for Action, and finds he is in no mood to compromise

DAVID Handley, chairman of Farmers for Action and the People's Fuel Lobby, is a Conservative voter and a conservative man. But this week he is giving William Hague the same message he's giving Gor- don Brown: we want a 26.2 pence per litre cut in the tax on petrol and, if we don't get it, we will grind you under our gumboots. What, then, can we expect to happen next?

It's been strange watching depressed dairy farmers grow into media stars and boiler-suited Che Guevaras. Strange and rather worrying. If the Countryside Alliance is the provisional wing of the Country Landowners' Association — as is sometimes said — the People's Fuel Lobby is 'The Real Countryside Alliance'. They want fuel costs to be the same across Europe and, whether this ambition is real- istic or not, they are determined to achieve it. They simply aren't talking the same lan- guage as anyone at Westminster.

`Nobody is going to give you a 26.2 pence tax cut,' I told Mr Handley plain- tively when I caught him by mobile tele- phone, standing among his cows in a farmyard in South Wales. 'Well, that's where talks start,' he replied. There was a steely edge to his soft burr. 'The three pence off fuel tax the Tories were talking about in September is an insult.' I explained that the three pence had merely referred to the government's tax revenue surplus, the amount Gordon Brown could have cut in taxes on fuel without a new budget. However, I knew William Hague wouldn't be bandying around any specific figures on what kind of cuts they might make.

I had just talked to the shadow agricul- ture minister Tim Yeo to find out what they might cut. It was touchy-feely stuff, with the emphasis on feely. They 'under- stand the devastating effect of high fuel taxes, especially in the countryside'. How- ever, it would be 'irresponsible' to put a figure on exactly where it becomes so very devastating. What, then, would they do for Mr Handley? Much was made of the gov- ernment sitting in London 'drinking Chardonnay' and failing to feel Mr Hand- ley's pain. But Mr Yea also mentioned that the Conservatives would cut red tape and bind up officialdom. They will do something about the food-labelling rules that allow foreign pork into a British pie. They will stop the British habit of being the first to impose Euro-regulations. In short, they will pay attention to the coun- tryside.

The plans, as I described them, were music to the ears for Mr Handley. He paused, like a soothed beast. 'I am pleased, obviously,' he told me, but (and here there was the sound of the girding of loins) 'we don't want any other deals on the table'. Not even if Gordon Brown made people with rural postcodes a special fuel-tax deal? 'We're not interested in any- thing like that. It has to be for everyone.'

So what next? 'On 14 November we are going to have 500,000 people demonstrat- ing against high fuel taxes in Hyde Park.' That seemed to be a lot of people. 'B... but,' I stuttered, 'there aren't that many farmers and hauliers.' Who were the 500,000 going to be?

`It's towns and villages. We are going to bring the country to London.' I had heard that phrase before. Had the Real Country- side Alliance asked the old Countryside Alliance for advice on the logistics or any- thing? After all, they had some experience of organising large-scale rallies. 'No,' was the short answer. As I well knew, the Alliance had refused to support the Farm- ers and Hauliers Alliance blockade of Manchester in June. They had said that demonstrations that cause disruption to the public wouldn't advance the farmers' cause. David Handley doesn't 'have time for them any more' and, in any case, 'the last thing we need is people with hunting banners'. The People's Fuel Lobby would rather make common cause with the Greens who until now have been the most vocifer- ous supporters of a high fuel tax.

`We are all family people,' Mr Handley explained. 'We care about the environ- ment. But fuel taxes aren't helping it. Look at what's going on with the trains. That money hasn't gone on public transport. All that it means is that heavier European lor- ries come over here with dirtier diesel. We don't receive revenue from them because they fill up at home and then come and pollute this country and the world environ- ment.' Handley plans to meet representa- tives of Greenpeace this Friday. An accommodation between the two sides would take the wind from the sails of those left-wing politicians and journalists who have spent the past decade demonising farmers as social and economic undesir- ables who rape the countryside. But it seems too much to hope for.

Rather, I fear that the Countryside Alliance were right. All the black propagan- da about hospitals being put in danger by the September fuel blockades has sensitised the public to any suggestions that the 'Peo- ple's Lobby' is holding the country to ran- som. The government is going to exploit this to the limit. And they are already putting tremendous pressure on the police to come down hard on the smallest breach of the law by fuel protesters. I asked Hand- ley if this didn't worry him 'As long as everyone is careful to keep within the law, all will be well.' But he knows he can't guar- antee that. Farmers are not used to working together or taking orders from anyone. They live quiet, almost isolated lives, and the fact that a few have become public fig- ures is causing jealousy and confusion.

Brynle Williams, the Welsh smallholder who emerged as a leader of the Stanlow refinery blockade, has, bizarrely enough, been accusing Handley of setting up splin- ter groups. And not everyone is keen on going to London. Some believe their lead- ers will be invited to Downing Street and bought off, becoming mere clones of the top men in the National Farmers' Union. Others think that the police will use the Hyde Park demonstration 'to pick off the organisers'.

'Aren't you on bail at the moment?' I asked Mr Handley. Yes, he had been arrested during a protest at a meat plant in October, but he was only on bail until 13 November, 'which the police tell me is pure coincidence, and if you want to believe that, do so'.

For all his apparent confidence, Handley admits to not sleeping. He doesn't know who will join his rag-tag protest, or what to expect from the ranks of monochrome fig- ures that oppose him. This kind of revolt doesn't usually end well — but perhaps Mr Hague may yet find some benefit in it.

Previous page

Previous page