The last but not the final word

Paul Foot

ORWELL by Jeffrey Myers Norton, £19.95, pp. 380 Not another biography of George Orwell! Surely we've had enough already. Quite apart from the majestic 20 volumes of his work edited by Peter Davison, there are full-scale books on Orwell by (to name a few) Bernard Crick, George Woodcock, Michael Shelden, Tosca Fyvel, Raymond Williams, Patrick Reilly and John Atkins, not to mention collections of reminiscences and critical essays all devoted to the man who made it absolutely clear in his will that he didn't want anyone ever to write his biography.

Reading this beautifully published book, I kept stumbling on familiar stories and quotations, and wondering why Jeffrey Myers or anyone else should bother to re- cycle them. Part of the answer comes at once at the beginning of the book: the phe- nomenal popularity of Orwell's work. His two great satires, Animal Farm and Nine- teen Eighty-Four, sold between them 40 mil- lion copies in 60 languages. With a potential audience like that, boosted by Orwell's almost mandatory appearance on compulsory school and university reading lists throughout the English-speaking world, what ambitious publisher could fail to suggest Orwell to an established biogra- pher?

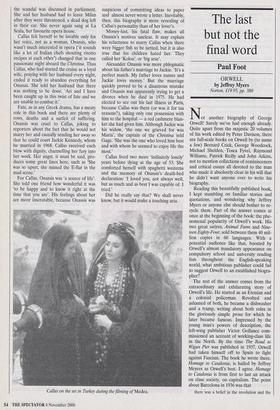

The rest of the answer comes from the extraordinary and exhilarating story of Orwell's life. He started as an Etonian and a colonial policeman. Revolted and ashamed of both, he became a dishwasher and a tramp, writing about both roles in the gloriously simple prose for which he later became famous. Impressed by the young man's powers 'of description, the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz com- missioned an account of working-class life in the North. By the time The Road to Wigan Pier was published in 1937, Orwell had taken himself off to Spain to fight against Fascism. The book he wrote there, Homage to Catalonia, is hailed by Jeffrey Meyers as Orwell's best. I agree. Homage to Catalonia is from first to last an attack on class society, on capitalism. The point about Barcelona in 1936 was that

there was a belief in the revolution and the

future, a feeling of suddenly having emerged into an era of equality and freedom. Human beings were trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine.

It was there, on the Aragon front, that Orwell's politics took root. It was there that he developed his lifelong hatred of Russian communism. He detested the Stalinists not because they were communists but because they were not. They represented not an alternative to capitalism but 'a planned state capitalism, with the grab motive left intact'. In 1938, such ideas were anathema on the Right and on the Left. Pretty well no one bought Homage to Catalonia. The wounded Orwell was drummed out of Spain by Stalin's secret police. When he came back to Britain he was politically iso- lated. He joined the BBC but was sickened by the jingoism he found himself broad- casting. In 1943 he joined the staff of Tri- bune, edited by Aneurin Bevan, where, in spite of his colleagues' distaste for his anti-Russian and anti-Zionist ideas, he wrote some of his best journalism. Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were both inspired not, as so many imagine, by Orwell's despair about socialism, but by an anguished desire to warn the Left of the menace of Stalinist totalitarianism.

Most of this is elegantly set down in this biography, but it soon becomes clear that Jeffrey Meyers is much more interested in Orwell the man than in his politics. Orwell admitted that his novels were 'lifeless' except when he was writing about politics, and Myers's narrative duly loses its vitality when it strays from politics. Though Myers insists his account is critical, it teeters on the edge of hagiography. There is no criti- cism of Orwell's homophobia nor of Orwell's decision at the very end of his life to give a list of suspect commies to a for- mer girlfriend who he knew was working for British intelligence. Myers describes this blatant witch-hunting as 'necessary, even commendable', and quotes the crusty Cold Warrior Robert Conquest to the effect that by shopping suspect Lefties to the British state Orwell 'did his patriotic duty' (what fun George Orwell would have made of his patriotic duty!).

The end of the book is marred, as Michael Shelden's was, by a splenetic attack on Sonia Browning, who married Orwell shortly before he died. Here are all the hallmarks of masculine prejudice against women who dare to interfere in a male literary world. Sonia Orwell didn't like sex, we are told, and so was probably a lesbian. Moreover, she leeched on Orwell's reputation and became a 'blowsy drunk'. Best of all, she is dead and can issue no writs. Fortunately for her, the four volumes of Orwell's essays, journalism and letters, which she edited with Ian Angus and which were published with her sensitive introduc- tion in 1968, are a far stronger shield of George Orwell's reputation than all of Myers and Shelden put together.

Previous page

Previous page