Auberon Waugh on new novels

October Ferry to Gabriola Malcolm Lowry (Cape £2.25) The Bitter Harvest William Haggard (Cassell £1.50) The Charlestown Scheme Richard Akerman (Eyre and Spottiswoode £2.50) To the best of my knowledge, nobody has yet written a study of authors' wives. Of course, there is no particular reason why anybody should, except that the English literature industry has now grown to such absurd proportions with the publication of more and more far-fetched comparative studies that is seems a curious omission. In my experience, authors' wives divide into those gentle, self-effacing creatures who suffer the discomforts and indignities of an author's life without complaining and the pushing, violent type who is determined to establish not only that its husband is the greatest and best of his kind but also, in a mysterious way, that all credit for this belongs properly to the wife.

For those who have not had the good fortune to meet her, it Is plainly quite impossible to judge which school Mrs Marjorie Bonner Lowry might grace. Most of us by now have got over the shock and acute sense of loss which were caused by her husband's death in June 1957. Since then, his memory has been kept alive by a trickle of volumes — collected short stories, selected poems and selected letters, all edited in whole or in part by his widow. This is the first full-length novel she has given us under his imprint and its pedigree is an interesting one.

In October 1946 Mr and Mrs Lowry travelled by Greyhound bus from Victoria to Nanaimo, and from there took the ferry to Gabriola Island, British Columbia. This would be quite an adventure for anyone, of course, but for a writer it must be classed as essential raw material, probably discountable against income tax. Mrs Lowry takes up the story: " As always we took notes, and when we returned we decided we had a short story, which we wrote together. But we decided it wasn't really first rate, and it was put aside."

Then in 1951, Lowry wrote to his agent claiming to have 'completely redrafted and largely rewritten' the novella believing it to be 'a hell of a fine thing.' However, Mrs Lowry reveals that 'two months before his death, he wrote from The White Cottage, Sussex, England,' saying that he was still engaged on a huge and sad novel ... called October Ferry to Gabriola'! Fourteen years after his death it has appeared.

The story is that of a journey, by husband and wife, in a Greyhound bus and later in a ferry, from Victoria to Nanaimo and Gabriola Island. The dust cover describes it as 'essentially a love story, the account of a marriage as it is evoked by the speeding images Ethan Llewellyn sees from the window of a bus.' It is true that there are endless flashbacks on the journey, which take our hero and heroine through the whole gamut of walking, talking, courting, engaged, banns up and married. The author, however, saw it somewhat differently: "It deals with the theme of eviction" (he wrote), "which is related to man's dispossession, but this theme is universalized." This is what he believed to be "one hell of a fine thing."

Now it is true that there is a recurring suggestion throughout the book that their journey is only necessary because they are threatened with eviction from their home where they were squatters. On arrival at the journey's end, they learn that the squatters have been reprieved by the acting mayor, but decide nevertheless not to return. It does not add up to a universalized theme of dispossession, and it is bogus rubbish to pretend it does. Nor, quite honestly, do the series of flashbacks and endearments add up to a love story. The book is quite simply the account of a bus• journey, rather over-written in parts but pleasant and lyrical in others, such as might be written by any sixth former with literary aspirations to describe an outing for his school magazine.

I can quite understand why Mr Lowry decided on several occasions not to publish it, and I can even understand why Mrs Lowry gave priority to assisting with editions of his letters, short stories etc. It will not do much to enhance his reputation, and I should be slightly annoyed to think of my dear widow rooting around in drawers for such slight and inconsiderable trifles as this.

One final mystery remains. In her editor's note, at the end of the book, Mrs Lowry writes : "there are two themes unfinished in the book that I could not include without some writing myself, which I felt I should not do; every word must be Malcolm's." This, we must agree, was an admirably self-effacing decision to make. However, she gives as her second theme the fact that the hero, Eltham, was in retreat from his law practice because he had successfully defended a man who was guilty of a monstrous and hideous murder, believing him innocent. As a matter of fact, this is already in the book, which must mean either that she changed her mind and wrote it in or that she omitted to read the book she had edited. Perhaps there is some richer and sinister explanation, but we must leave the mystery to be solved by a later generation of literary detectives.

William Haggard's new thriller, about the six days' war in the Middle East, is preposterously unconvincing but worth waiting for in paperback to while away a long train journey. A dim but worthy backbench MP is approached by Arabs with a £20,000 bribe to make a pro-Arab speech in the House of Commons. As if this was not unlikely enough, he refuses, so the Arabs try to compromise him by sending a naked lady into his room while he is asleep and photographing her. Annoyed by this, the MP makes a strongly pro-Israel speech, whereupon the Arabs try to murder him and kidnap his daughter, double-crossing each other in the process. The central implausibility is unavoidable for anyone who has spent half an hour in the House of Commons, or who knows how unimportant backbench opinions are, but there are some good twists in the narrative which just manage to redeem it.

Haggard has been extravagantly praised by all the usual crowd — Julian Symons is quoted on the dustcover, so is H. R. F. Keating (twice) and Edmund Crispin (three times). But he is so wildly out in his assessment of the importance attached to backbench speeches that I can only have the gravest doubts about everything else he has written. I suppose he is an agreeable person to meet, which is something, after all.

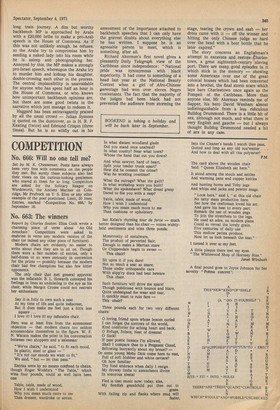

Richard Akerman's first novel gives a pleasantly Daily Telegraph view of the Caribbean since independence : "National pride was synonymous with black superiority. It had come to something of a head last year at the National Beauty Contest when a girl of Afro-Chinese parentage had won over eleven Negro contestants. The fact that the majority of the judges had been black had not prevented the audience from storming the stage, tearing the crown and sash — her dress came with it — off the winner and hitting the only Chinese judge so hard over the head with a beer bottle that he later expired."

The story concerns an Englishman's attempt to excavate and restore Charlestown, a great eighteenth-century slaving port. There are many good episodes in it which stick in the memory — showing some Americans over one of the great colonial houses which had been converted Into a brothel, the final storm scare which lays bare Charlestown once again as the Pompeii of the Caribbean. More than anyone else, Mr Akerman reminds me of Sapper, his hero David Wenham almost indistinguishable from a less ridiculous Bulldog Drummond. There is a little bit of sex, although not much, and what there is very English and gauche — but I always thought Bulldog Drummond needed a bit of sex in any case.

Previous page

Previous page