A SHORTAGE OF GOOD MEN

Japan's Liberal Democratic Party has none, turned against it as well

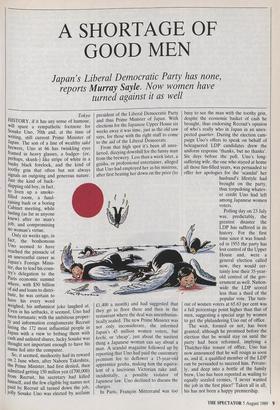

Tokyo HISTORY, if it has any sense of humour, will spare a sympathetic footnote for Sosuke Uno, 70th and, at the time of writing, still current Prime Minister of Japan. The son of a line of wealthy sake brewers, Uno at 66 has twinkling eyes framed in heavy glasses, a badger- (or, perhaps, skunk-) like stripe of white in a bushy black forelock, and the kind of toothy grin that often but not always signals an outgoing and generous nature.

Just the kind of back- slapping old boy, in fact, to liven up a smoke- filled room, a fund- raising bash or a boring Cabinet meeting, while lusting (as far as anyone knew) after no man's job, and compromising no woman's virtue.

Only six weeks ago, in fact, the bonhomous Uno seemed to have reached the pinnacle of an uneventful career as Japan's Foreign Minis- ter, due to lead his coun- try's delegation to the Paris economic summit where, with $50 billion of aid and loans to distri- bute, he was certain to have his every word weighed, his unfunniest joke laughed at. Even in his setbacks, it seemed, Uno had been fortunate; with the ambitious proper- ty and information conglomerate Recruit listing the 172 most influential people in Japan with a view to bribing them with cash and unlisted shares, lucky Sosuke was thought not important enough to have his name fed into the computer. So, it seemed, mediocrity had its reward on 2 June when, after Naboru Takeshita, the Prime Minister, had first denied, then admitted getting 150 millon yen (D00,000) from Recruit, his secretary had killed himself, and the few eligible big names not job, Jolly by Recruit all turned down the ob, Jolly Sosuke Uno was elected by acclaim president of the Liberal Democratic Party and thus Prime Minister of Japan. With elections for the Japanese Upper House six weeks away it was time, just as the old saw says, for those with the right stuff to come to the aid of the Liberal Democrats. From that high spot it's been all unre- lieved, dizzying downhill for the funny man from the brewery. Less than a week later, a geisha, or professional entertainer, alleged that Uno had employed her as his mistress, after first beating her down on the price (to

£1,400 a month) and had suggested that they go to floor there and then in the restaurant where the deal was unenthusias- tically sealed. The new Prime Minister was not only inconsiderate, she informed Japan's 45 million women voters, but kechi, or 'cheap', just about the nastiest thing a Japanese woman can say about a man. A scandal magazine followed up by reporting that Uno had paid the customary premium fee to deflower a 15-year-old apprentice geisha, making him the equiva- lent of a lascivious Victorian rake and, incidentally, a possible violator of Japanese law. Uno declined to discuss the charges.

In Paris, Francois Mitterrand was too

busy to see the man with the toothy grin, despite the economic basket of cash he brought, thus endorsing Recruit's opinion of who's really who in Japan in an unex- pected quartier. During the election cam- paign Uno's offers to speak on behalf of beleaguered LDP candidates drew the uniform response 'thanks, but no thanks'. Six days before the poll, Uno's long- suffering wife, the one who stayed at home all those fun-filled years, was persuaded to offer her apologies for the 'scandal' her

husband's lifestyle had brought on the party, thus torpedoing whatev- er credit Uno had left among Japanese women voters.

Polling day on 23 July

was, predictably, the greatest disaster the LDP has suffered in its history. For the first time since it was found- ed in 1955 the party has lost control of the Upper House and, were a general election called now, they would cer- tainly lose their 35-year- old control of the gov- ernment as well. Nation- wide the LDP scored less than a third of the popular vote. The turn-

out of women voters at 65.63 per cent was a full percentage point higher than that of men, suggesting a special urge by women to get the philandering Uno out of office.

The wish, formed or not, has been granted; although he promised before the election that he would stay on until the party had been reformed, implying a Thatcher-like tenure of office, Uno has now announced that he will resign as soon as, and if, a qualified member of the LDP can be persuaded to succeed him. Private- ly, and deep into a bottle of the family brew, Uno has been reported as wailing to equally sozzled cronies, 'I never wanted the job in the first place!' Taken all in all, his has not been a happy premiership.

But what, we might wonder, does it mean? Has the government of the world's strongest economic power been seized by a gang of lecherous rogues, incompetent ones at that? Spectator readers have already been alerted ('A yen for bribes', 21 January 1989) that the Recruit scandal would shake the foundations of the Japanese political system, but may well have thought that, even so, any one of them could have run a better campaign than the boozy crew who have just re- ceived such a shattering rebuff from the voters — a performance all the more stunning because the Japanese economy is booming, unemployment, inflation and strikes are unknown, and the opposition is divided and mostly tainted with Recruit money itself.

The fact is, we are seeing something more fundamental than the discomfiture of some not-so-good old boys who have been wrong-footed by events and urges outside their control, more basic even than a revolt by Japanese women or a universal rejec- tion of corruption that, going on too long, has got completely out of hand. The political basis of Japan's extraordinary climb out of the ashes of defeat has irrepar- ably broken down, largely because of its own success, and a new politics is strug- gling to be born. To gauge its outlines we need to look back at the origins of the system that brought the amorous Uno so briefly and comically to power.

Who are the LDP, who can find no one better than these buffoons to lead them to slaughter at the polls? The party was formed after the war by the amalgama- tion of the remnants of two pre-war par- ties, the Seiyukai and Minseito (approx- imately 'liberal' and 'democratic') which, back in the prosperous 1920s, played Bug- gins' turn in parliament, much as Liberal and Tory once did in Britain. In the first election held on universal manhood suf- frage in 1928 eight 'proletarian' candidates got in as well, forerunners of the Japan Socialist Party which, under Miss Takdko Doi, a former lady professor of law, did as well in the Japanese elections last week as Uno and Co did badly.

In short, Japan was once moving in a direction which would, in the fulness of time, have very likely produced a democra- tic order recognisably out of the same stable as those of the other maritime industrial nations, Britain and the United States, with whom relations in those days were cordial. Older Japanese remember those years fondly as the 'Taisho democra- cy', named after the present Emperor's grandfather, when Japan had 'normal con- stitutional government' and every woman in the world wanted a pair of Japanese silk stockings.

The good times soon began to evapo- rate. The first Great Depression wiped out silk exports; Europe and America and their colonial empires closed to Japanese manufacturers. The Japanese army, look- ing for an answer to Japan's economic problems on the Asian mainland, man- oeuvred the country into war with China and eventually took over the government at home. In August 1940 all political parties were dissolved. Two months later the army launched a new one, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association.

The 1RAA was the closest Japan ever got to a fascist party, although it staged no rallies and heiled no Fiihrer. It shared, however, one idea with most authoritarian and fascist regimes and all the traditional Confucian cultures of Asia, namely that the nation should be one big happy family and that those who criticise the govern- ment or offer alternative policies are no better than ingrates and traitors and belong in jail or exile. The IRAA contested one election in 1942, and with no opposition and a generous distribution of secret army funds in the rural areas predictably did well, with 381 of the 466 seats in the Lower House. It disappeared in 1945 along with much other wartime scaffolding, but the IRAA retains an historical interest because it was the parent, or at the very least the accoucheur, of the LDP.

Post-war Japanese politics got off to a confused start. Apart from the Communist Party, whose leadership (including the present chairman, Kenji Miyamoto) spent the war years in jail, almost all the promin- ent pre-war politicians of the Minseito, the Seiyukai and the Socialist Party had col- laborated patriotically with the IRAA. the first post-war election was won by Inchiro Hatoyama of the old Seiyukai, who was promptly purged by General Douglas MacArthur for his IRAA connection. MacArthur had a low opinion of all politi- cians and preferred, like his Shogun prede- cessors, to govern directly through the Japanese bureaucracy, especially the ones who had produced miracles of munitions production for the war against the United States.

A decade later Japan was no longer an enemy to be punished but an ally to be rebuilt and remotivated for the global crusade against communism. The bombed- out Japanese industrial cities where two million civilians died were (and still are) the strongholds of the Socialists, who argued that Japan's alliance with the Un- ited States might lead the country into another war. In October 1955 the sepa- rated branches of the Socialist Party reunited and did ominously well in a snap election, on a platform of neutralism and the abolition of the Japanese self-defence forces. A month later, various conservative parties, groups and grouplets came together to form the LDP. In essence, it is exactly the same party that was slaughtered at the polls last week, and an odd party it is, unlike any other in the world, or in Japanese history (except the IRAA).

To begin with, in the panic of the moment the fledgling LDP decided to include every shade of Japanese opinion to the right of the fearsome Socialists. These people have never had a coherent outlook, ranging all the way from philosophers of the free market like the late and compara- tively honest Takeo Miki to a small but well-dug-in wing of unrepentant wartime nationalists whose diplomatically gauche remarks about the war have repeatedly brought far more suspicion on Japan than its policies actually deserve.

West Germany and Italy have left such diehards to wither, or flourish, out of office, while the LDP has had to endure oafs like the present agriculture minister, who remarked during the campaign that Miss Doi was unqualified for national leadership because she has had no husband or children — only to be icily reminded that, at 61, she belongs to the generation of Japanese women whose chances of mar- riage were blighted by the deaths of a million young men in the war enthusiasti- cally supported by elements of the LDP. This exchange probably cost Uno's party whatever credit it still had among Japanese women of the liberated persuasion, a small but growing band.

Then again, the LDP inherited from the IRAA the network of village notables whose personal influence did much to keep Japan fighting to the bitter end. With no war in prospect, these rustics can only be politically organised on a 'person-to-person basis, and this has demanded a constant stream of cash — money for drinks parties, for outings, for gifts of pianos to primary schools, presents for weddings, funerals, new businesses and so on. Mostly the LDP's money has come from businessmen, but in 1955 Japanese business had little cash to spare. Yoshio Kodama, one-time gangster, wartime Japanese secret agent in Shanghai and Japan's foremost post-war political and business fixer, is widely credited with putting up the funds on which the LDP was floated. Kodama himself claimed the money was raised by selling loot he had gathered in China. 'Trunks full of gold, boxes of diamonds, room after room of them,' he once told a gullible interviewer. A likely tale, considering that Kodama was arrested in 1945 as a suspected war crimin- al and had his assets minutely combed by the CIC, forerunner of the CIA, for whom he later worked. A central figure in the Lockheed scandal, Kodama has since gone to his reward without spilling any sensa- tional beans, but an American source for the LDP's grubstake seems to have been, in the spirit of those times, at least on the cards.

Certainly, the LDP has always presented itself as the party of the American connec- tion. This was a sure vote-getter in the days when many Japanese believed that Uncle Sam's rockets were all that stood between them and the dictatorship of the proletariat or the status of a Chinese or Soviet satellite. These days the United States, pushing for the opening of the Japanese rice, beef and orange markets and thus destitution for Japan's remaining seven per cent of genuine farmers, is an albatross around the LDP's neck. With most of its strength in the countryside, the party has been operating against the natural move- ment of Japan's population to the cities, making the loyalty of farmers and small businessmen all the more essential to it — and steadily increasing its bulimic hunger for money.

The LDP's origins in the war years and the tribal sense of wartime unity, Japan's `spirit of the Blitz', are reflected in the Party's peculiar treatment of its opposition which has, contrary to much that has been written, no basis in Japan's earlier political traditions. Instead of putting contested matters to a vote the LDP has preferred to negotiate its legislation through, often waiting years for an uneasy consensus with the opposition parties (always excluding the Japan Communist Party, the untouch- ables of Japanese politics, who need not be consulted). This arrangement has been enforced by the threat of the opposition parties to walk out and thus shatter notion- al unity.

Only twice has this strange unwritten rule been broken — once in 1960, when the first revision of the US Mutual Security Treaty was 'railroaded' through the Diet by Nobosuke Kishi, who had to resign his premiership in expiation, and again this spring, when Uno's predecessor, Naboru Takeshita, in the absence of the opposition rammed through the budget, including a three per cent universal commodity tax bitterly resented by Japanese housewives, and later paid the same penalty. In its relationship to the bureaucracy, too, the LDP bears the mark of the years during and just after the lost war, to the point where it has been nicknamed the `Bureaucratic Rule Assistance Associa- tion'. When the Japanese cabinet theoreti- cally recovered its authority in 1952 the bureaucracy had been running the country under Japanese and then American gener- als for close to 20 years, by which time they had established a power unmatched in the non-communist world. The bureaucracy is not, however, a united administration, but a patchy set of independent satrapies per- petually squabbling over jurisdiction. The various ministries have close connections with the businesses they are supposed to be supervising, and the businessmen in turn subsidise politicians, mostly of the LDP, to intercede with the bureaucrats.

These triangular 'tribes', as the Japanese call them, carry on as-if they were indepen- dent countries, responsible to no one but themselves. The result is that Japanese export industries, for instance, have a robust ministry, the dreaded MITI, that cares for nothing but their interests, while there are no ministries for imports, housing or social amenities, all left to fend, more or less anaemically, for themselves. The further result is Japan's earth-shaking, gigantic trade surpluses. The system of bureaucratic capitalism has, on the positive side, certainly recon- structed the Japanese economy, although in a lopsided way, and by insulating the economic process from the demands of either consumers or shareholders managed to do so without either the cyclical unem- ployment or (until recently) the contrast of wealth and comparative poverty that reg- ularly destabilises other, less disciplined capitalist societies. It has also, by Darwinian selection, produced a breed of politician unique in the world. These men (the LDP has, like the old Japanese army, little use for women's brains) cannot make a persuasive speech or present a clear policy, because they have never had to, but they are masters of backhand fund-raising, closed- door intrigue and impenetrable double- talk. No wonder their colleagues from other countries have found it hard to communicate with them and mistakenly assumed that the Japanese for some strange oriental reason prefer their leaders to operate in this devious fashion. The Japanese voters have, in fact, rejected two LDP old-timers straight out of the classical mould, Prime Ministers Naboru Takeshita and cheery, evasive Sosuke Uno. What went wrong? Bad luck, of course (there was no need for the Recruit Co to put its list of bribeworthy politicians, offi- cials and journalists in its computer so that the investigators could simply print them out, and it was careless of the firm's chief fixer to proffer a bribe in front of a concealed television camera), but the more

fundamental problem for the LDP has been the changes, demographic and social, that have come with Japan's success.

The farmers, once its mainstay, are giving up the unequal battle to make a living from tiny farms, even at Japanese food prices, and moving into town. The enormous tide of export profits that has flowed into Japan in the past decade has had the unwanted side effect of pushing up land prices (38 times in Tokyo since 1955) and splitting the middle class into a minor- ity who benefit from land ownership, the tochi-richi or 'land rich', who love the LDP, and the majority, battling to find mortgages, accommodate their aged pa- rents in from the country and keep small businesses afloat, who do not. All of these people are beginning to wonder aloud when the fruits of Japan's success, now, they suspect, being cornered by the 'tribes' of conniving bureaucrats, politicians and businessmen will be more widely distri- buted among the industrious Japanese tribe as a whole.

Japan Inc may well be in for some perestroika and a return to something like `normal constitutional government' after an enormous detour through war and dictatorship, but the Japanese are certainly not going against the world tide by taking up socialism, and the vote for Miss Doi's party was largely a vote for the lady herself. Unlike Uno she ran a faultless campaign, promptly purging the party of the one member who confessed to a minor flirtation with Recruit and summarily drumming out a candidate who used influ- ence to get the Bullet Train to make an unscheduled stop so that he could appear on the same platform as Miss Doi. (He won his seat anyway and has since rejoined the party, so the whole incident may have been shrewdly engineered to show that the JSP runs a tight ship.) Women undoubtedly voted for Miss Doi, not out of some sisterly sympathy but for the same reason men did — she spoke simply and clearly on television, a medium the LDP has never liked or learnt to use, and pointed out the obvious, namely that the LDP's style of cash-and-carry-on poli- tics no longer responds to Japan's needs, either at home or internationally. Her sex was significant, it is widely believed, only as a guarantee that her party's policy had not been negotiated in sake bars, smoke- filled rooms or geisha houses. And of course, this conservative island nation awash with tea and male chauvinists could hardly be the first in all East Asia with a woman prime minister.

Right, Ted Heath?

Previous page

Previous page