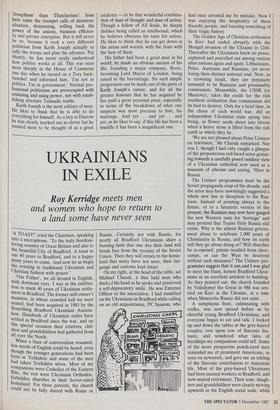

UKRAINIANS IN EXILE

Roy Kerridge meets men

and women who hope to return to a land some have never seen

`A TOAST!' cried the Chairman, speaking into a microphone. 'To the truly freedom- loving country of Great Britain and also to the beautiful City of Bradford. A toast to our 40 years in Bradford, and to a happy many years to come. And now let us begin the evening in traditional Ukrainian and Christian fashion with prayer.' :Our Father', we all droned in English, with downcast eyes. I was at the celebra- tion to mark 40 years of Ukrainian settle- ment in Bradford. The former mill-owner's mansion, in whose crowded hall we were seated, had been acquired in 1983 by the flourishing Bradford Ukrainian Associa- tion. Hundreds of Ukrainian exiles have settled in Bradford since the war, and on this special occasion their relatives, chil- dren and grandchildren had gathered from all over the North. When a buzz of conversation resumed, few words of English could be heard, even though the younger generations had been born in Yorkshire and some of the men had taken Yorkshire wives. Most of my companions were Catholics of the Eastern Rite, the rest were Ukrainian Orthodox, forbidden churches in their Soviet-ruled homeland. For these patriots, the church could not be fully shared with Rome or Russia. Certainly not with Russia, for nearly all Bradford Ukrainians share a burning faith that one day their land will break free from the tyranny of the Soviet Union. Then they will return to the home- land that many have not seen, their lan- guage and customs kept intact. On my right, at the head of the table, sat Michael Charuk, a thin bald man who ducked his head as he spoke and preserved a self-deprecatory smile. He was External Officer to the association. I had stumbled on the Ukrainians in Bradford while calling on an old acquaintance, PC Sansom, who had once arrested me by mistake. Now I was enjoying the hospitality of these friendly people, and learning something of their tragic history.

The Golden Age of Christian civilisation in Kiev had ended abruptly with the Mongol invasion of the Ukraine in 1240. Thereafter the Ukrainians knew no peace, captured and parcelled out among various alien nations again and again, Lithuanians, Poles, Austrians and Russians, yet never losing their distinct national soul. Now, as a crowning insult, they are popularly assumed to be Russians and presumably communists. Meanwhile, the USSR (or Muscovy), takes the credit for the rich southern civilisation that communism did its best to destroy. Only for a brief time, in the chaos of each world war, did an independent Ukrainian state spring into being, as flower seeds shoot into bloom when a heavy stone is lifted from the rich earth in which they lie.

`We are not pleased about Peter Ustinov on television,' Mr Charuk remarked. Nor was I, though I had only caught a glimpse of the preposterous red-faced actor gestur- ing towards a carefully posed outdoor view of a Ukrainian cathedral now used as a museum of atheism and saying, 'Here in Russia . . .

The Ustinov programmes must be the Soviet propaganda coup of the decade, and the actor may have unwittingly suggested a whole new line in deception to the Rus- sians. Instead of pointing always to the future, or to a futuristic version of the present, the Russkies may now have gauged the new Western taste for `heritage' and may pretend that Tsarist Holy Russia still exists. Why is the atheist Russian govern- ment about to celebrate 1,000 years of Christianity in Russia, and how on earth will they go about doing so? Will churches be re-opened, priests recalled from slave- camps, or can the West be deceived without such measures? The Ustinov pro- grammes suggest that it can,and I was glad to meet the blunt, honest Bradford Ukrai- nians as an excellent antidote to humbug. As they pointed out, the church founded by Volodymyr the Great in 988 was cen- tred on Kiev in the Ukraine, at a time when Muscovite Russia did not exist.

A sumptuous feast, culminating with vodka, was now spread before us by cheerful young Bradford Ukrainians, and everyone began to eat and talk. I looked up and down the tables at the grey-haired couples, row upon row of Slavonic fea- tures, and wondered what tales of hardships my companions could tell. Some of the more prosperous pouch-eyed men reminded me of prominent Americans, as seen on newsreels, and gave me an inkling of the Slavonic contribution to American life. Most of the grey-haired Ukrainians had been manual workers in Bradford, and now neared retirement. Their sons, daugh- ters and grandchildren were clearly moving upwards in the English social scale, while remaining resolutely Ukrainian.

`Am I allowed to write down your name?' I asked Mr Charuk. 'Some of the others here have told me that they fear the KGB will track them down.'

`I'm not afraid!' he said. 'My mother once wrote, "Do what you do, it could not be worse for us." My family are already being persecuted at home. I have had no letter for three years, so anything could have happened. Since 1963, I have been secretary of the Captive Nations Commit- tee. Apart from the Ukraine, the other nations represented are Byelorussia, Esto- nia, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania. There is also a Lithuanian Club here in Bradford. Many people came here during and after the war, and worked as wool-combers and the like, in the mills.

`In 1945, Stalin declared that the author- ities would catch up with every one of the refugees who chose to live in the West.

That is why people have to be careful. It was Stalin who organised the enforced famine in the east Ukraine, to compel the people to submit to collective farms. Seven million of our people died, in 1932 and 1933.

`So when war broke out, and the Germans invaded, we thought they could not be worse than the Russians. Our nation began to revive, but then the Germans dashed it down again. My village was surrounded by German soldiers at dawn. I was a young man of 16, and they offered me the choice of slave-camp starvation in the north, or joining the army. So I chose the army. All the time I fought on the Eastern Front, fought Russians. We all refused to go to the Western Front. Yet now we hear allegations everywhere that we are war criminals. These rumours have been started by the KGB, who have falsified documents, in order to spread this story.' Mr Charuk paused to roll a cigarette. A Fleet Street editor, now exiled to the East End, had indeed told me with a laugh that the Ukrainians in England were war cri- minals.

I complimented Mr Charuk on his English. `I was put on agricultural work when I was brought here, and picked up English from Land Army girls. Men would only teach us swearwords and pretend they were good English. Before I could speak good English, I would go to Woolworth's and self-service shops where I could take what I wanted without asking.'

Nothing changes, for only that morning I had been the guest of a Pakistani family in Bradford whose little boy of four peppered his speech with four-letter words. The Urdu-speaking adults smiled benignly, but the boy's older brothers and sisters seemed rather perturbed. 'The boys at school taught him those words, and he doesn't know what they mean,' one of the children had told me.

Michael Charuk told me that his move- ments in Britain had been restricted by the Ministry of Agriculture until 1951. Every- one of his generation agreed on that date as the time when they ceased to be sent here and there to work, like semi- prisoners.

`Men lived in hotels, apart from their wives,' he told me. 'Only 30 Ukrainians were sent to Bradford after the war, mostly ladies who worked in the mills. I worked on farms all over the place before I came here, in Cambridgeshire, Essex and Suf- folk. For a long time I worked restoring the canal at Ipswich, using cement. I have spent 17 years wool-combing and the last 18 years in the building trade. Communists tell my countrymen, back home, that Ukrainians in England are suffering tor- ments, but it's not so.'

Aspeech boomed from the rostrum. Mr Charuk busily translated it into English for me. In between speeches, a loudspeak- er played Ukrainian music. 'You can hear something of the mountains in that tune,' my new friend commented. 'It originated in the Carpathian mountains, and the tempo is that of your Scottish Highland music.'

Mr Charuk had to leave before the drinking of the last toast. A three-man band of Ukrainians from Leeds and Brad- ford then took the stage, and many elderly couples took to the floor and waltzed solemnly. To my ears the musicians, a drummer, guitarist and accordion-player, were playing bland, unexciting versions of Scottish airs, but they were very popular none the less. In a corner, a group of self-possessed eight-year-old boys and girls, some with vivid blond mops of hair, danced in wilder Cossack-style, arms folded and legs kicking about. Others performed country dances learned at Ukrainian Saturday School, bobbing, bow- ing and seizing one another's hands and tripping to and fro. None of them knew they were being watched. After a time, I introduced myself.

`Are you Ukrainian or English?' I asked them.

`Both!' they instantly chorused.

`Oh no, not English, I'll never be En- glish,' one girl exclaimed. Her English mother, who turned up at that moment, remonstrated with her.

More and more parents drifted across, in a kindly mood, to see who was talking with their children. Little Nadia, who wore a white flower in her hair, was the daughter of the red-dressed girl who served behind the bar (which had now opened).

`I'm a Heinz 57,' the barmaid told me cheerfully. 'My father's Ukrainian, my mother's Italian, and was born at Ilkley. My real job's a nurse, I'm only helping out tonight.'

`My parents both met in Germany, at a displaced persons' camp at the end of the war,' her husband told me. 'They came to Hull on two separate ships, and then got sent to the DP camp at Malvern. From , there they were sent to farms in Scotland. Dad had to report to the police regularly until 1951. As soon as he was free to move, he came to Bradford, where he met people he had known in his home village in the Ukraine.'

Other parents and grandparents spoke of working down coalmines and (more recently) on the buses. One elderly man spoke heatedly about the Jews. 'Who created the communist state? The Jews! They created it! Beria was a Jew, the man responsible for the famine. Many commis- sars were Jews.'

What could I say? My Jewish grand- father, who once lived at Lvov, capital of the Western Ukraine, had thrown himself zealously into the cause of communism. Family legends say that he helped to send Lenin from Switzerland to Russia in a sealed train. However, my grandfather had never known or practised the Jewish reli- gion. Neither had most of the communist Jews of his day. He and his family, as far as I know, regarded the Ukraine as Russia.

Curly-haired Larysa, a well-mannered child with a pretty smile, owned a satur- nine bearded Dad who was suspicious of me. Like PC Sansom, he looked at my ragged clothes, and wondered if I could really be a writer. Plastic-bag-journalism has found it hard to survive the Fall of Fleet Street.

`You mustn't be surprised if I follow you when you leave,' he warned. 'As for the Jews, we are not anti-Semitic. My parents and my mother-in-law's parents sheltered Jews from the Germans. My mother-in-law witnessed the famine of 1933. Children were shot for eating blades of grass, and cannibalism took place, with raiding par- ties who stole children and ate them. My parents, at the ages of 14 and 15, were taken to forced labour camps in Germany. After the war, my father signed up with the French Foreign Legion rather than be repatriated. The Allies realised something was amiss when the Cossacks committed suicide rather than be sent back to Russia. So many Ukrainians were sent here as stateless DPs. England needed them for cheap labour.'

Here he stared at me through cynical spectacles, and then continued. 'I speak fluent Ukrainian. When at work I feel English and at home I feel Ukrainian. Sometimes somebody at work asks me how I got my long surname, and then I feel Ukrainian again for a moment. The Ukraine was the only country to proclaim its independence when the Nazis arrived. Russia had its own Ukrainian troops, and sometimes brother fought against brother.'

As I left the friendly Ukrainian Associa- tion, I could see family parties, quite united, sitting gossiping at the overladen tables. Wishing the Ukrainians goodbye, I walked through an empty moonlit city to my room at Manningham. My steps rang out on the deserted pavement, but nobody followed me.

Previous page

Previous page