Exhibitions 3

Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman

(The Art Institute, Chicago, till 10 January)

Devotion to work

Roger Kimball

In some ways it is unfortunate that the single best picture in this retrospective of Mary Cassatt's work is a portrait of the artist by her friend Edgar Degas. Painted in the early 1880s, 'Mary Cassatt Seated, Holding Cards', shows the artist in her mid-to late-thirties (she died in 1926), a dark, elegantly garbed figure leaning for- ward, the only articulated thing in a field of scumbled russets, browns, and grey-white brushstrokes. Perhaps she is deliberately showing her hand of cards; perhaps she has lost interest in the game and has inadver- tently let her hands drop. In any event, her gaze — pensive, intent, lost in a middle dis- tance beyond the picture frame — suggests that her mind is elsewhere.

As indeed it might be. Cassatt was just then entering the period of her greatest work. Born in Pittsburgh in 1844, the fourth of five surviving children in a rich, cultivated family, Cassatt had been travel- ling and studying in Europe since she was 20. Her first encounter with Degas's work — some pastels of dancers — in 1874 was a revelation: 'the turning point in my artistic life', she later described it.

The admiration was mutual. 'She has infinite talent,' Degas remarked — charac- teristically adding that 'no woman has a right to draw like that'. In 1877, he invited her to exhibit with the Impressionists (she was the only American to do so) after her two Salon entries for that year had been rejected. For the next 15 years or so she produced dozens of fetching pictures that made her — along with that other ex-pat painter, John Singer Sargent (d. 1925) among the most affectionately regarded American artists of her generation.

Hyperbole is an accepted tool of publici- ty, and no one will be surprised that the claims made for Cassatt's work in the pro- motional literature accompanying this exhi- bition are rather larger than her achievement can support. And given the ideological temper of the day, no one will be surprised, either, that the feminist gam- bit has been played early and often in the commentary on Cassatt's work. The 'mod- ern woman' subtitle genuflects firmly in this direction, as do the essays in the cata- logue for the exhibition. Likewise, readers who turn to Nancy Mowell Mathews's intelligent biography of the artist (Yale, 1994) will find the feminist gong tapped at regular intervals.

There is some justification for this. Cas- satt was a crusader for women's suffrage she even sacrificed friends over the issue. Although many of her most famous — and some of her best — pictures celebrate motherhood, she herself never married, never indulged in any love affairs. She devoted herself to her independence and her work. She was a shrewd businesswom- an, buying and selling the art of her Impressionist friends and advising the great dealer Paul Durand-Ruel and the collector Louisine Havemeyer, one of her closest friends.

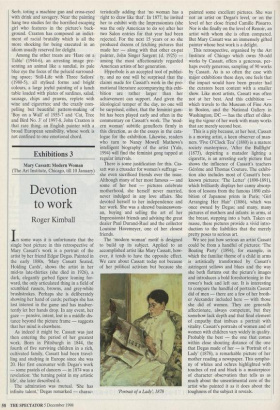

The 'modern woman' motif is designed to build up its subject. Applied to an accomplished artist like Mary Cassatt, how- ever, it tends to have the opposite effect. We care about Cassatt today not because of her political activism but because she `Portrait of a Lady, 1878 painted some excellent pictures. She was not an artist on Degas's level, or on the level of her close friend Camille Pissarro. Nor is she finally on the level of Renoir, an artist with whom she is often compared. But Mary Cassatt was an immensely gifted painter whose best work is a delight.

This retrospective, organised by the Art Institute of Chicago which owns 50-odd works by Cassatt, offers a generous, per- haps overly generous, sampling of 90 works by Cassatt. As is so often the case with major exhibitions these days, one feels that the impact would have been greater had the curators been content with a smaller show. Like most artists, Cassatt was often not at her best. And this exhibition which travels to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the National Gallery in Washington, DC — has the effect of dilut- ing the vigour of her work with many works that are merely second best.

This is a pity because, at her best, Cassatt is a moving artist, a keen observer of man- ners. 'Five O'Clock Tea' (1880) is a mature society masterpiece, 'After the Bullfight' (1873), depicting a matador lighting a cigarette, is an arresting early picture that shows the influence of Cassatt's teachers Gerome and Thomas Couture. The exhibi- tion also includes most of Cassatt's best- known pictures: 'The Letter' (1890-1891), which brilliantly displays her canny absorp- tion of lessons from the famous 1890 exhi- bition of Japanese prints in Paris; 'Girl Arranging Her Hair' (1886), which was once owned by Degas; and many, many pictures of mothers and infants: in arms, at the breast, stepping into a bath. Taken en masse, these pictures provide a vivid intro- duction to the liabilities that the merely pretty poses to serious art.

We see just how serious an artist Cassatt could be from a handful of pictures: 'The Boating Party' (1894), for example, in which the familiar theme of a child in arms is artistically transformed by Cassatt's astringent yellows and blues and the way she both flattens out the picture's images and introduces a bold foreshortening in the rower's back and left oar. It is interesting to compare the handful of portraits Cassatt did of men — there are a few of her broth- er Alexander included here — with those she did of women. They are generally affectionate, always competent, but they somehow lack depth and that final element of empathy that imbues a portrait with vitality. Cassatt's portraits of women and of women with children vary widely in quality. Probably the best — the one that comes within close shouting distance of the one that Degas made of her — is 'Portrait of a Lady' (1878), a remarkable picture of her mother reading a newspaper. This sympho- ny of whites and ochres highlighted with touches of red and black is a masterpiece of character observation that tells us as much about the unsentimental core of the artist who painted it as it does about the toughness of the subject it reveals.

Previous page

Previous page