1. Magical mystery tour ? TRAVEL

TREVOR GROVE

The f50 limit, of course, was something of a wind-fall for the package-tour merchants. This year, with devaluation to boot, even more of Its will be going by the brochure—and going east by all accounts, if Spain is to be as crowded as a devalued peseta suggests.

Of all the East European countries Yugo- slavia attracts the most British tourists (about 250,000 last year), partly because the natural progress is from west to east and partly because Yugoslavia was the first to establish com- mercial and cultural ties with the West. This

has its dangers of course. The middle-class British tourist is a notorious misanthrope. In sandals and baggy khaki shorts, pink-skinned and sunhatted, he is apt to trudge miles under a burning sun in search of his own private Nitria. The Montenegrin littoral, surely one of the most delightful coastlines in the world and fertile ground for such adventuring, is fast becoming, not 'crowded' in the Costa Brava sense of the word, but 'known,' certainly. So are the islands. The real isolationist will have to live on a boat—or go inland, avoiding Postojna's magnificent caves and the sixteen lakes of Plitvice; avoiding the minarets of Mostar and Sarajevo and the Byzantine monas- teries with their superb frescoes; avoiding the `symbolic knightly jousts' that are a special tourist torture endemic to Yugoslavia.

Nowhere, of course, at least nowhere with a pleasant climate, can you get right away from other people who are trying to get right away from other people. Eastern Europe is still relatively virgin ground. Nevertheless, Poland had 33,000 British tourists last year, Bulgaria about the same, while Rumania, 11 ungar y and Czechoslovakia were not far behind. Though Yugoslavia has gone maverick as far as the Warsaw Pact is concerned, all these countries share certain 'tourist features': they are all inexpensive (Rumania offers British tourists a 200 per cent premium on the official exchange rate, Hungary 56 per cent, to be increased this year, and Poland a premium of I3s in the £ if you spend over £2 6s a day), they all have poor roads, good climates, beautiful scenery, socialism and a tendency to stage manifesta- tions folkloriques at the slightest encourage- ment.

Poland is the coolest of the six, its climate seldom much hotter than our own; addicts of Sopot's 'Amber Coast,' on the Baltic, claim otherwise. For myself I prefer rocky coves to bleak open beaches, whatever their amber con- tent and whatever their nostalgia value as fin de siecle spas. Zakopane and the Tatras moun- tains would make an ideal holiday setting, but if you're already familiar with Swiss-Alpine scenery Mazurias might be more enticing—a strange other-world of forests, impenetrable marshes and a thousand lakes, famous as a natural wild-fowl preserve. As for Warsaw, its habitues speak with shining eyes of its café society, the sophistication and charm of its predominantly Roman Catholic citizens. Poland is the baby of the tourist trade hereabouts but already it has a boom on its hands, so much so

that it has had to convert over 15,000 'historical monuments' into hotels, including, so a native source proudly informed me, 'dungeons, granaries and mills.'

Bulgaria has also been hotel building madly. Its tourist trade, like that of Rumania, is biased towards the Black Sea. There the com- parison stops. The Rumanian resorts seem to be resorts and nothing more, artificially created to house a seasonal and undiscriminating population. The Bulgarian resorts, on the other hand, show sophisticated plan- ning and a care to western tastes. The hotels are modern, but discreetly so, set in gardens and grouped round a nucleus of restaurants, night-clubs and shops. The idea is to promote a village bonhomie among the guests who otherwise might have to trek into Varna for their night-life; despite the walk to breakfast and the queues for lunch (particularly bad when there is a Russian coach tour in) the system works well. The quietest, the most old-fashioned and perhaps the nicest resort on the Bulgarian coast is Drouzhba, though gayer souls might prefer Golden Sands or Sunny Beach—as the state tourist board would have us call Zlatni Pyassatsi and Slun- chev Bryag.

Bulgaria may have its Rose Valley as well as its beaches, but only the Rumanians could provide a brochure that tells you how to say 'I have a sensitive skin' in their charming language. Inland their country is certainly worth visiting: the Carpathian mountains; the Danube delta with its fantastic. bird life (but take plenty of mosquito repellent), and above all, the magnificent frescoes of the Moldavian churches and monasteries, most famous of them Sucevita, Humor, Bistrita and the peerless Moldovita.

Czechoslovakia and Hungary are both land- locked. At this Hungarians are apt to look coyly at the heavens and mutter something self- deprecating about the 'Hungarian Sea.' Lake Balaton is, in fact, something of an inland ocean, fifty-five miles long, providing all the pleasures of the seaside without the beastly salt. But on the whole it is a country, like Czecho- slovakia, for motion rather than for stasis; by all means don't miss the lake, but do include in your itinerary Budapest, Sopron and the 700 year old castle at Koszeg.

Czechoslovakia also has its lakes, the most beautiful of them set amongst the mountains of Southern Bohemia, and a new artificial lake, so far unexploited, in the heavily wooded area of Vihorlat. But the most interesting part of the country is Bohemia itself with its rivers and encircling mountains and, at its centre, Prague. Prague is arguably the most beautiful city in Europe. Certainly it contains some of Europe's most famous monuments—the Cle- mentium, Bohemian headquarters of the Jesuits in the sixteenth century; the Carolinum, the city's 'Old University' built by Richard II's father-in-law Charles IV; and the astounding high baroque of St Clement's Church. The music festival, by the way, starts on 12 May this year.

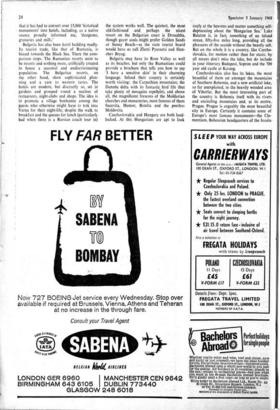

Getting to all these places is not as compli- cated as the nomenclature might suggest. BEA and national airlines fly `in harness' to all six countries, return fares ranging between £48 and £80 depending on your destination. (Sabena also flies, though not always direct, to the six capitals; Air India touches down in Prague on its way to Moscow.) Train services are excellent and average £20 less than the corresponding air_ fares, e.g. Prague £28, Sofia £41, Bucharest £49 return. Coaches are cheaper and often more comfortable. A new sleeper-coach service (by Fregata Travel) to Prague, -Cracow, Poznan and Warsaw actually beats the train there. Pack- age tours are still the most economical way of doing things, costing anything between £55 and £150 per person for an all-in fortnight (the less you move around the less the price—f150 is Grand Tour stuff. . .).

, Or, of course, you can go by car. This is probably the most, congenial way of seeing Eastern Europe and allows you to choose your own erratic course of exploration. With..the £25 car allowance as an extra bonus and if you're prepared to forgo the luxury hotels, you can reckon on spending about 0 lOs a day per head, all in. And if you camp, cheaper still. Take the usual spares and all the necessary _ visas, and don't forget to be polite to the border guards. Their guns are loaded.

Previous page

Previous page