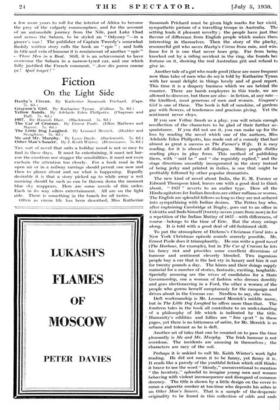

Fiction

On the Light Side

1957. By Hamish Blair. (Blackwood. 7s. 6d.)

THE sort of novel that suits a holiday mood is not so easy to find in these days. It must be entertaining, it must not har- row t he emotions nor stagger the sensibilities, it must not even enchain the attention too closely. For a book read in the open air or in a railway carriage should permit one now and then to glance about and sec what is happening. Equally desirable it is that a story picked up to while away a wet morning should be such as can be thrown down the moment blue skv reappears. Here are sonic novels of this order. Each in its way offers entertainment. All are on the light side. There is something in the bunch for all tastes.

Often as circus life has been described, Miss Katherine

Susannah Prichard must be given high marks for her vivid, sympathetic picture of a travelling troupe in Australia. The setting lends it pleasant novelty ; the people have just that flavour of difference from English people which makes them interesting in themselves. Then the story of the plucky, resourceful girl who saves Harby's Circus from ruin, and wins fame for it is one that never loses grip. Far from being knocked out by a riding accident in the ring, she founds her fortune on it, showing the real Australian grit and refusal to give in.

Another tale of a girl who made good (these are more frequent now than tales of men who do so) is told by Katharine Tynan with her usual delight in things lovely and of good report. This time it is a drapery business which we see behind the counter. There are harsh employers in this trade, we are allowed to discover, but there are also—in fiction, at any rate— the kindliest, most generous of men and women. Grayson's Girl is one of these. The book is full of sunshine, of gardens gay with flowers, of tenderness and gracious giving. Yet the sentiment never cloys.

If you saw Yellow Sands as a play, you will retain enough recollection of the characters to be glad of their further ac- quaintance. If you did not see it, you can make up for the loss by reading the novel which one of the authors, Miss Adelaide Eden Phillpotts, has made out of a comedy that had almost as great a success as The Farmer's Wife. It is easy reading, for it is almost all dialogue. Many people dislike reading plays in play form. This method of publishing them, with " said he " and she roguishly replied," and the stage directions smoothly incorporated in the story instead of being jerky and printed in italics, is one that might be profitably followed by other popular dramatists.

The new kind of novel about India, the E. M. Forster or Edward Thompson kind, leaves one with a good deal to think about. " 1957 " reverts to an earlier type. Here all the Hindu agitators for Indian freedom are either ruffians or worms. The English are splendid fellows so long as they are not seduced into sympathizing with Indian desires. The Fettes boy who, after captaining Cambridge at Rugby, goes out to an office in Calcutta and finds himself (twenty-seven years from now) in for a repetition of the Indian Mutiny of 1857—with differences, of course—belongs to the time of Eric. But the story swings along. It is told with a good deal of old-fashioned skill.

To put the atmosphere of Dickens's Christmas Carol into a New York Christmas episode sounds scarcely possible. Mr. Ernest Poole does it triumphantly. He can write a good novel (The Harbour, for example), but in The Car of Croesus he lets his fancy riot and provides some excellent diversions of humour and sentiment cleverly blended. Two ingenicais people buy a car that is the last cry in luxury and hire it out for twenty pounds a day. The hirers and their doings supply material for a number of stories, fantastic, exciting, laughable. Specially amusing are the wives of candidates for a State Governorship, one a woman of fashion who dresses dowdily and goes electioneering in a Ford, the other a women of the people who gowns herself sumptuously for the campaign and drives about in the Croesus car. Needless to say, she

Deft workmanship is Mr. Leonard Merrick's middle name, but in The Little Dog Laughed he offers more than that. The fourteen tales in the book all contribute to an undcr3tanding of a philosophy of life which is indicated by the title. Humanity's oddities and follies are " fine sport " in these pages, yet there is no bitterness of satire, for Mr. Merrick is as urbane and tolerant as he is deft.

Another set of tales that can be counted on to pass the time pleasantly is Me and Mr. Murphy. The Irish humour is not overdone. The incidents are amusing in themselves ; the characters are racy of the soil.

Perhaps it is unkind to call Mr. Keith Winter's work light reading. He did not mean it to be funny, yet funny it is. It reads like a parody of the youthful fiction which still thinks it brave to use the word " bloody," unconventional to mention " the lavatory," splendid to imagine young men and women behaving with violent inconsequence and disregard of common decency. The title is shown by a little design on the cover to mean a cigarette smoker at tea-time who deposits his ashes in an Other Man's Saucer. That is a sample of the desperate originality to be found in this collection of odds and ends

from other books as crazy as itself. A lot of fun can be got out of it.

Previous page

Previous page