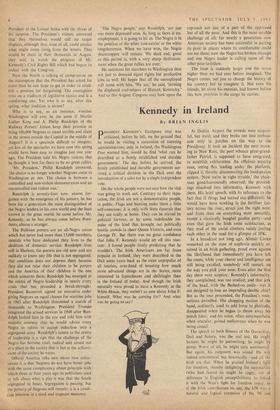

The Long Hot Summer

From MURRAY KEMPTON.

NEW YORK

MR. KI:NNEDY travelled among the ruins of the Christian Democracy. Mr. Goldwater rose from the ruins of white Southern sensibilities to be more and more the probable if less and less the plausible Republican candidate for President. Yet no one here seems to notice; all our attention is diverted because the Negro goes on enforcing his own informal history, unpredictable and barely understood.

He must seem at a distance an obsession. Still, what else could be said to have happened in a week when the President of the United States called thirty Negro leaders to the White House to say that he hoped that there would be no great demonstrations in Washington during the ten days of his European tour because if there were he might have to come back? A year ago, the Negro was a disturbance only to Southern sheriffs; now he has risen to confront even the President of the United States with the threat of his Surprise. The President's visitors answered that they themselves would call no major displays, although they, least of all, could predict what might come rising from the streets. They would be there in their thousands in August, they said, to watch the progress of Mr. Kennedy's Civil Rights Bill which had begun its ordeal with the Congress.

Now the North is talking of compromise on the assumption that the President has asked for more than he can hope to get in order to estab- lish a position for bargaining. The assumption rests on a tradition of legislative tactics and is a comforting one. Yet who is to say, after this spring, what tradition is secure?

Who is to say, as an instance, whether Washington will ever be the same if Martin Luther King and A. Philip Randolph of the Railway Porters' Union keep their promise to bring 100,000 Negroes to stand terrible and silent in the streets outside the Capitol in the middle of August? It is a spectacle difficult to imagine; yet few of the spectacles we have seen this spring would have been easy to imagine just one year ago. The President told his Negro visitors that he thought it best for there to be no great rallies.

'Mr. President,' Philip Randolph answered, 'the choice is no longer whether Negroes come to Washington or not. The choice is between a' controlled and non-violent demonstration and an uncontrolled and violent one.'

Randolph is seventy-four now, almost for- gotten with the emergence of his juniors; he has been for a generation the most distinguished of the Negro leaders in his own world and the least known in the great world; he came before Mr. Kennedy, as he has always, come before Presi- dents, almost a stranger.

The Pullman porters are an all-Negro union which has never had more than 15,000 members, menials who have dedicated their lives to the abolition of domestic service. Randolph lives still in Harlem; the porters are old now and are unlikely to know any life that is not segregated; that condition does not depress them because they did not raise their children to be porters and the America of their children is the one which concerns them. Randolph has emerged at the centre of Negro leadership in nearly every crisis that has, preceded a break-through: President Roosevelt signed an executive order giving Negroes an equal chance for wartime jobs in 1943 after Randolph threatened a march of

thousands to Washington. President Truman integrated the armed services in 1948 after Ran-

dolph looked him in the eye and told him with majestic courtesy that he would advise every Negro to refuse to accept induction into a segregated army. Randolph's return to the centre of leadership is a sign that the challenge of the Negro has becothe total, radical and aimed not at a place in the society that is but at the achieve- ment of the society he wants.

Official America talks now about how unfor- tunate it is that Negroes do not have better jobs with the same complacency about principle with which three or four years ago its politicians used to talk about what a pity it was that the South segregated its buses. Segregation is passing; but the poverty al Negroes will remain; it is a condi- tion inherent in a tired and stagnant economy, 'The Negro people,' says Randolph, 'are just one more depressed area. As long as there is un- employment, it is going to hit us. The Negro is in the position of the white hod-carrier or the white longshoreman. When we have won, the Negro sharecropper will remain. We shall end, great as this period is, with a very sharp disillusion- ment when the great rallies are over.'

He summons his marchers to Washington then not just to demand equal rights but productive jobs as well. He hopes that all the unemployed will come with him. 'We are,' he said, 'inviting the displaced coal-miners of Hazard, Kentucky.' And so this August, Congress may look upon the

reproach not just of a part of the oppressed but of all the pool:. And this is the most terrible challenge of all; for nearly a generation now American society has been successful in putting its poor in places where its comfortable could not see them; now the Negro has broken through and one Negro leader is calling upon all the other poor to follow.

The issue is suddenly larger and the terms higher than we had ever before imagined. The Negro comes, not just to change the history of his country but to complete it. Not even his friends, let alone his enemies, had known before Ibis how precious is the cargo he carries.

Previous page

Previous page