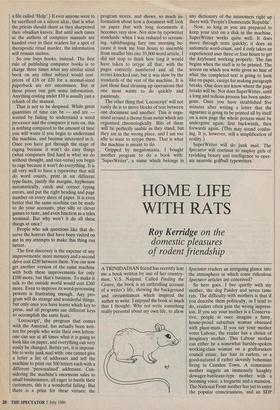

HOME LIFE WITH RATS

Roy Kerridge on the

domestic pleasures of rodent friendship

A TRINIDADIAN friend has recently lent me a book written by one of her country- men, V.S. Naipaul. Called Finding the Centre, the book is an enthralling account of a writer's life, showing the background and circumstances which inspired the author to write. I enjoyed the book so much that I thought: Why not write something really personal about my own life, to allow Spectator readers an intriguing glance into the atmosphere in which some ridiculous Spectator articles are conceived?

So here goes. I live quietly with my mother, the dog Paisley and seven tame rats. The difficulty with mothers is that if you describe them politically, as I tend to do, readers often gain the wrong impress- ion. If you say your mother is a Conserva- tive, people at once imagine a fussy, house-proud suburban woman obsessed with place-mats. If you say your mother votes Labour, the reader has a choice of imaginary mother. This Labour mother can either be a somewhat harshly-spoken working-class woman on a godforsaken council estate, her hair in curlers, or a good-natured if rather slovenly bohemian living in Camden Town. A communist mother suggets an immensely haughty dowager-battleaxe-type mother with a booming voice, a lorgnette and a mansion. The National Front mother has yet to enter the popular consciousness, and an SDP mother suggests nothing at all.

As my mother resembles none of these mothers, we will pass over mothers entire- ly. There is little to say about the dog Paisley, except that he resembles his name- sake, so that brings us straight to the seven rats.

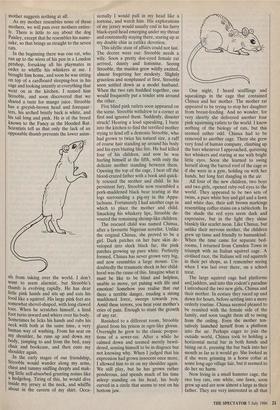

In the beginning there was one rat, who ran up to the wires of his pen in a London petshop, forsaking all his playmates in order to whiffle his whiskers at me. I brought him home, and soon he was sitting on top of a cardboard sleeping-box in his cage and looking intently at everything that went on in the kitchen. I named him Strooble, and soon discovered that we shared a taste for mango juice. Strooble has a greyish-brown head and forequar- ters, his arched bristly back is white, and his tail long and pink. He is of the breed known to the Fancy as the Hooded Rat. Scientists tell us that only the lack of an opposable thumb prevents the lower anim- als from taking over the world. I don't want to seem alarmist, but Strooble's thumb is evolving rapidly. He has dear little pink hands and sits up and eats his food like a squirrel. His large pink feet are somewhat shovel-shaped, with long clawed toes. When he scratches himself, a hind foot turns inward and whirrs over his body. Sometimes he licks his hands and rubs his neck with both at the same time, a very human way of washing. From his seat on my shoulder, he runs up and down my body, jumping to and from the bed, easy chair and bookcase, and then onto my shoulder again. In the early stages of our friendship, Strooble would wander along my arms, chest and tummy sniffing deeply and mak- ing little self-absorbed grunting noises like a hedgehog. Tiring of this, he would dive inside my jersey at the neck, and whiffle about in the cavern of my shirt. Occa- sionally I would pull in my head like a tortoise, and watch him. His explorations of my jersey would usually end in his furry black-eyed head emerging under my throat and contentedly staying there, staring up at my double chin in ratlike devotion.

This idyllic state of affairs could not last. The decree went out: Strooble needs a wife. Soon a pretty doe-eyed female rat arrived, dainty and feminine. Seeing Strooble, the maiden grew wildly excited, almost forgetting her modesty. Slightly graceless and nonplussed at first, Strooble soon settled down as a model husband. When the two rats huddled together, one would frequently put a tender arm around the other.

Five blind pink ratlets soon appeared on the scene. Strooble withdrew to a corner at first and ignored them. Suddenly, disaster struck! Hearing a loud squeaking, I burst into the kitchen to find the terrified mother trying to fend off a demonic Strooble, who had grown to twice his natural size, a ruff of coarse hair standing up around his body and his eyes blazing like fire. He had killed four of his children, and now he was hurling himself at the fifth, with only the delicate mother standing between them. Opening the top of the cage, I beat off the blood-crazed father with a book and quick- ly rescued the mother and child. In his persistent fury, Strooble now resembled a pork-maddened black bear tearing at the logs surrounding a pig-sty in the Appa- lachians. Fortunately I had another cage in which to place the mother and child. Smacking his whiskery lips, Strooble de- voured the remaining shrimp-like children.

The rescued child was named Chinua, after a favourite Nigerian novelist. Unlike the original Chinua, she proved to be a girl. Dark patches on her bare skin de- veloped into sleek black fur, the pink patches growing up pure white. Perfectly formed, Chinua has never grown very big, and now resembles a large mouse. Un- doubtedly the traumatic shock in her child- hood was the cause of this. Imagine what it must be like to be blind and helpless, unable to move, yet pulsing with life and emotion! Somehow you realise that out there a terrible danger, exuding a strong maddened force, sweeps towards you. Amid these terrors, you hear your mother's cries of pain. Enough to stunt the growth of any rat.

Banished to a different room, Strooble glared from his prison in ogre-like gloom. Overnight he grew to the classic propor- tions of a sewer-rat. After a while he calmed down and seemed merely bewil- dered, sensing himself to be in disgrace but not knowing why. When I judged that his expression had grown innocent once more, I allowed him to sit on my shoulder again. We still play, but he has grown rather ponderous, and spends much of his time asleep standing on his head, his body curved in a circle that seems to rest on his bottom jaw. One night, I heard scufflings and squeakings in the cage that contained Chinua and her mother. The mother rat appeared to be trying to stop her daughter from breast-feeding. And no wonder, for very shortly she delivered another four pink squirming ratlets to the world. I know nothing of the biology of rats, but this seemed rather odd. Chinua had to be removed to another cage. There she grew very fond of human company, climbing up the bars whenever I approached, quivering her whiskers and staring at me with bright little eyes. Soon she learned to swing herself along the barred roof of the cage as if she were in a gym, holding on with her hands, her long feet dangling in the air.

All four of the new children, two boys and two girls, opened ruby-red eyes to the world. They appeared to be two sets of twins, a pure white boy and girl and a fawn and white duo, their soft brown markings resembling coffee stains on a tablecloth. In the shade the red eyes seem dark and expressive, but in the light they shine blankly like scarlet neon. Like Chinua, but unlike their nervous mother, the children grew up tame and friendly to humankind. When the time came for separate bed- rooms, I returned from Camden Town in triumph with an Italian squirrel cage. A civilised race, the Italians sell red squirrels in their pet shops, as I remember seeing when I was last over there, on a school treat.

The large squirrel cage had platforms and ladders, and into this rodent's paradise I introduced the two new girls, Chinua and their mother. In ecstasy they raced up and down for hours, before settling into a more orderly routine. Chinua seemed pleased to be reunited with the female side of the family, and soon taught them all to swing from the ceiling. Even the mother ten- tatively launched herself from a platform into the air. Perhaps eager to join the outside world, Chinua took to holding a horizontal metal bar in both hands and biting on it, pressing the bar back into her mouth as far as it would go. She looked as if she were grinning in a horse collar at some long-ago village fair, but it seemed to do her no harm.

Now living in a small hamster cage, the two boy rats, one white, one fawn, soon grew up and are now almost a large as their father. They are very interested in all that goes on, and have merry, boyish disposi- tions, rolling over in play and pretending to bite one another. Five year old David from next door has named them Leon and Slasher. Rats are very unlike mice in temperament. They do not dart, they saunter. Leon and Slasher share some of the best qualities of pigs and bears. When they stand up and gaze at someone, they could easily be bears surprised in a forest glade, or pigs with trotters on the rim of their sty, eagerly awaiting the slush- bucket. Sometimes one of them gazes boarlike at the world, his head emerging from the door and resting on the ground like that of any pig dreaming in his sty.

But Chinua, the vivid black and white miniature rat, is my delight. Light as a feather and soft to the touch, she knows all her father's tricks and performs them with lightning speed. First she is on my bed, then on my knee, my shoulder and the top of the bookcase, all in an instant. I feel a light touch on the leg or shoulder and she is away, soaring like a flying squirrel. V.S. Naipaul might summon his Muse through boyhood neighbours or African forest pagans, but I am more than satisfied with such inspiration as is given to me by my little fairy rat.

Previous page

Previous page