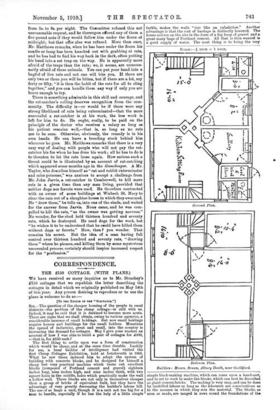

RAT-CATCHERS.

THE occupation of the rat-catcher seems likely to be revived. The outbreak at Freston, in Suffolk, of what appears to be pneumonic plague, both in human beings and in such animals as hares, rabbits, ferrets, and rats, has led to a vigorous campaign directed against rats first and foremost, as being undoubtedly concerned in carrying germs of disease. Consequently the services of professional and amateur rat- catchers have been required on a large scale, and if other localities follow the example of Freston, it should prove a good season for the profession,—as one of the best-known rat- catchers has named it, preferring that description to the mere word " trade " or "calling." The rat-catcher has always been a picturesque and rather mysterious being. He does not dress quite so handsomely to-day as the rat-catcher described by Pennant in 1812, but with his sacks and traps he is still worth looking at. Pennant in his "British Zoology" tells us that, "among other officers, his British Majesty has a rat-catcher, distinguished by a particular dress, scarlet embroidered with yellow wonted, on which are figures of mice destroying wheat-sheaves." Possibly this Royal rat- catcher may have been related to one Robert Smith, who in 1768 published a "Universal Directory for taking alive and destroying Rate and all other kinds of four-footed and winged Vermin," in which he describes himself on the title-page as " Rat-catcher to the Princess Amelia." Possibly, too, the Royal rat-catchers of the Georges are ancestors of the very men who are employed, it is true without embroidered mice on their jackets, in destroying rats to-day. The secrets of the profession would naturally descend from father to sou, just as they do with gamekeepers.

What are the rat-catcher's secrete? How is it that he has come by his reputation of being able to clear buildings of rats when other means have failed, and how does he manage, given favourable conditions, to destroy such pro- digious quantities ? Doubtless the secret trick or prescription is less mysterious than he would have you believe it to be, but that the cleverest rat-catchers have got re-all,/ valuable "dodges" of their own there can be no doubt. one of the earliest recollections of the present writer was the visit of a rat-catcher to an old house in Gloucestershire. He was a travelling rat-catcher, and he offered to clear the place of rats, but would let nobody know how he was going to do it. All that was seen was that he went into a building with a sack which was apparently filled with hay. He left it there for some time and then drew the strings tight round the neck of the sack, which was full of rats. How the rats were induced to go into the sack nobody could find out; that was his secret. He doubtless wanted the rats alive, probably for some beerhouse encounter, for he did not use poison. Probably, indeed, no rat-catcher of those days would use poison if he could get his rats alive, partly because there was generally a market in live rats, and partly because poison has always been recognised as uncertain and dangerous. Johnson, the author of the " Gamekeeper's Directory," published about 1850, tells us that one of the best ways of destroying rats in large quantities is with pills made of newly ground malt mixed with arsenic, but that the use of poison in this way needs the greategt possible care. A friend of his, he writes, once 'employed a professional rat-catcher to clear his premises of these vermin, which the man accomplished ; but in effecting this desirable object he poisoned a pig, three pea fowls, and an old favourite wild duck,"—truly a mixed bag for a professed rat-catcher.

Some years ago a Manchester member of the calling, Mr. Ike Matthews, published a little book with the attractive title, "Full Revelations of a Professional Ratcatcher," in which be gives the results of an experience of twenty-five years. His revelations are as interesting as they are plain and straightforward. There is, you gather, no secret at all. But there are many precautions which must be taken. In the first place, you must never use poison in buildings, or you may leave a dead rat behind you, and that, to put it on the lowest ground, is bad business. Once Mr. Matthews, under a floor, on his stomach with two candles in his hands, saw his ferret kill a large bitch rat about six yards away against a wall, where he could not reach it. He therefore left it there. Two or three weeks afterwards he was required to return and take up the floor, and, he adds reflectively, "was never sent for again." He tells us after this the best way to trap. You begin by strewing about the rats' runs, say, thirty little heaps of fine sawdust mixed with oatmeal. The rats get used to playing in and out of the sawdust and oatmeal, and then one fine day you hide a steel trap in each little heap, and you will catch one rat per heap. But you cannot go on for ever catching rats in sawdust. They get tired of it. So after a little you give them their thirty heaps made of soot, and pro- ceed in the same way ; then after the soot you can make a change to shredded paper. You must be careful to handle the traps as little as possible, or the rats will be suspicious; and a good tip is to pour a drop or two of oil of aniseed or oil of rhodium on the trap,—scents which attract rats beyond all others. But, generally speaking, Mr. Matthews believes in going to work with simple weapons, and he has little praise for the strange and exotic. The best thing he knows for clearing young rats is a good cat. "A good eat can do as much in one night when rats are breeding as two ferrets can do in a day." Both dogs and cats, too, he thinks, are better than a mongoose, though there is one advantage in using a mongoose: it always brings out the rats it kills, and never leaves them behind under the floor. The great thing, in every ease, is for the rat-catcher to work in silence, and at night. The best time is just after dark, when rats are hungriest, and a rat-catcher's work in buildings should be over by midnight.

The rat-catcher's calling, Mr. Matthews thinks, should be dignified with the name of a profession, for it needs both learning and courage. It also entails extremely exacting work. Suppose, for instance, that in threshing a bay of wheat only half the bay has been threshed at nightfall, and there are known to be large numbers of rats in it. They must not be allowed to get out, and to prevent them from escaping the rat-catcher must lie on the top of the bay, or go about every thirty minutes and beat the bottom with sticks till daylight. Then the threshing-machine starts again, and the rat-catcher, for his trouble in staying awake all night, will get perhaps one hundred and fifty "good coursing rats." Or he used to get these good rats ; rat-coursing is now illegal. As for the courage needed by the rat-catcher, besides the skill and endurance, Mr. Matthews has often asked for help in his work, and has been refused it because people have been afraid. He has been under a. warehouse floor with a lot of rats in his traps, and he has been =able to get one man in fifty to come under the floor with him to hold the candle for him, much less handle the rate. Once, working at a hospital, and using one hundred and twenty traps, he asked for his fee to be raised from 5s. to Be. per night. The Committee refused this not unreasonable request, and he thereupon offered any of them a five-pound note if they would follow him under the floors at midnight; but that offer also was refused. More than once, Mr. Matthews remarks, when he has been under the floors his candle or lamp has been kneeled out with grabbing at rats, and he has had to find his way back in the dark, often putting his hand into a set trap on the way. He is apparently more afraid of the traps than the rats; we, it seems, are unneces- sarily afraid of these animals. You can put your hand into a bagful of live rats and not one will bite yea. If there are only two or three you will be bitten, but if there are a lot, say forty or fifty, "it is then the habit of the rats for all to cling together," and you can handle them any way if only you are brave enough to try.

There is something admirable in this skill and courage, and the rat-catcher's calling deserves recognition from the com- munity. The difficulty is—or would be if there were any strong likelihood of rats being exterminated—that the more successful a rat-catcher is at his work, the less work is left for him to do. He ought, really, to be paid on the principle of the doctor who receives a salary so long as his patient remains well,—that is, so long as no rats are to be seen. Otherwise, obviously, the remedy is in his own hands. He can leave a breeding stock behind him wherever lie goes. Mr. Matthews remarks that there is a very easy way of dealing with people who will not pay the rat- catcher his fee when be has done his work; all he has to do is to threaten to let the rats loose again. How serious such a threat could be is illustrated by an account of rat-catching which appeared some months ago in the Gamekeeper. A Mr. Taylor, who describes himself as" rat and rabbit exterminator and mice poisoner," was anxious to accept a challenge from Mr. John Jarvis, a rat-catcher in Camberwell, to kill more rats in a given time than any man living, provided that neither dogs nor ferrets were used. He therefore contracted with an owner of some buildings at Wisbech St. Mary to clear the rats out of a slaughter-house in which they swarmed. He "drew them," be tells us, into one of the sheds, and waited for the answer from Jarvis. None came, and be was com- pelled to kill the rats, "as the owner was getting nervous." No wonder, for the shed held thirteen hundred and seventy rats, which he destroyed. He used dogs for the work, but "he wishes it to be understood that he could have killed them without dogs or ferrets." How, then ? you wonder. That remains his secret. But the idea of a man having full control over thirteen hundred and seventy rats, "drawing them" where he pleases, and killing them by some mysterious unrevealed process, certainly should inspire increased respect for the "profession."

Previous page

Previous page