THE MOZART OF CHESS

uncomfortable champion

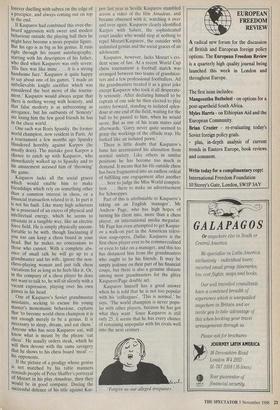

IT IS, as they say, lonely at the top. How much more lonely then, to be at the top of a profession in which isolation from the mainstream of society is a way of life. We are talking of chess, and in particular its world champion Garry Kasparov. For even within that isolated community, Kasparov is an outsider. To the Russian chess estab- lishment, based in Moscow, he is an unwelcome interruption, a young man from way out east — Azerbaijan — who in what to them sounds like a foreign accent makes it clear that he wants nothing to do with the old system of graft and pay-off. To

Anatoly Karpov, the man whom he de- throned as champion three years ago, and the leader of the Moscow clique, Kasparov is simply 'that Asiatic'.

But if Kasparov is not a popular figure among his rivals in the Soviet Union, he is hardly 'one of the lads' among his peers on the Western chess circuit. One reason is simply age. With the exception of Britain's absurdly talented Nigel Short, the top players are all well into their thirties — or older. Kasparov is still only 25. It is not just that the other national champions resent this fact in itself, but they had formed their chess circuit of rather friendly tournaments in luxury hotels before Kas- parov came on the scene.

They had a good system going: draw most of the games, win apologetically if one's opponent committed a rare blunder (and not even then if the result was fixed) and share the prize money around as evenly as possible. Then Kasparov came in and tried to win every game. It was integrity. And it was just not done.

Only a very rare kind of chess player can play in this way. Even the strongest grand- masters find it very difficult to win a game with the black pieces against one of their peers, if the opponent wishes only to draw. This is because modern chess has become dominated by technique rather than im- agination, and its exponents are ruled more by the fear of defeat, than by the hope of victory. Kasparov however, aided by the most extraordinary powers of cal- culation, has always been prepared to risk defeat in the quest for victory. He is, as the English grandmaster Jonathan Speelman puts it 'the archetypal warrior'. He is a kind of chess board version of Errol Flynn, forever duelling with sabres on the edge of a precipice, and always coming out on top in the end.

If Kasparov had combined this over-the- board aggression with sweet and modest behaviour outside the playing hall then he might have become a more popular figure. But his ego is as big as his genius. It runs right through his recent autobiography, starting with his description of his father, who died when Kasparov was only seven: `His face was like mine . . . it is a strong handsome face.' Kasparov is quite happy to say about one of his games, 'I made an unbelievable knight sacrifice which was Considered the best move of the tourna- ment.' Kasparov would always argue that there is nothing wrong with honesty, and that false modesty is as unbecoming as arrogance, but his outbursts of 'honesty' are losing him the few good friends he has In the chess world.

One such was Boris Spassky, the former world champion, now resident in Paris. At a tournament a few months ago Spassky blundered horribly against Karpov (he usually does). The mistake gave Karpov a chance to catch up with Kasparov, who immediately walked up to Spassky and to his amazement accused him of 'throwing' the game.

Kasparov lacks all the social graces which would enable him to make friendships which rely on something other than a common interest in chess, or a financial transaction related to it. In part it is not his fault. Like many high achievers he is possessed of an excess of physical and intellectual energy, which he seems to emanate in a tangible way, like an electric force field. He is simply physically uncom- fortable to be with, though fascinating if you too can keep a chess board in your head. But he makes no concessions to those who cannot. With a complete abs- ence of small talk he will go up to a grandmaster and his wife, ignore the non- chess-playing woman and just talk chess variations for as long as he feels like it. Or, in the company of a chess player he does not want to talk to, he will sit silently with a vacant expression, playing over his own games in his head.

One of Kasparov's Soviet grandmaster assistants, seeking to excuse his young master's monomanic behaviour, explains that 'to become world chess champion it is not enough merely to be a genius. It is necessary to sleep, dream, and eat chess.' Anyone who has seen Kasparov eat, will know what is meant by the phrase 'eat chess'. He usually orders steak, which he will then devour with the same savagery that he shows to his chess board 'meat' his opponents.

If the picture of a prodigy whose genius is not matched by his table manners reminds people of Peter Shaffer's portrayal of Mozart in his play Amadeus, then they Would be in good company. During the successful defence of his title against Kar- pov last year in Seville Kasparov stumbled across a video of the film Amadeus, and became obsessed with it, watching it over and over again. Kasparov clearly identified Karpov with Salieri, the sophisticated court insider who would stop at nothing to repel Mozart/Kasparov, the outsider with unlimited genius and the social graces of an adolescent.

Kasparov, however, lacks Mozart's evi- dent sense of fun. At a recent World Cup chess tournament a football match was arranged between two teams of grandmas- ters and a few professional footballers. All the grandmasters treated it as a great joke except Kasparov who took it all desperate- ly seriously. After declaring himself to be captain of one side he then elected to play centre forward, standing in isolated splen- dour at one end of the field, waiting for the ball to be passed to him, when he would score. But as one of his team mates said afterwards, 'Garry never quite seemed to grasp the workings of the offside trap. He looked like an isolated pawn.'

There is little doubt that Kasparov's fame has accentuated his alienation from normal society. Like others in similar positions he has become too much in demand. It means that his life outside chess has been fragmented into an endless ordeal of fulfilling one engagement after another . . here to judge the Miss World competi- tion . . . there to make an advertisement for Schweppes.

Part of this is attributable to Kasparov's taking on an English 'manager', Mr Andrew Page, who has high hopes of turning his client into, more than a chess player, an international media megastar. Mr Page has even attempted to get Kaspar- ov a walk-on part in the American televi- sion soap-opera, Dallas. Kasparov is the first chess player ever to be commercialised or even to take on a manager, and this too has distanced him from the grandmasters who ought to be his friends. It may be simply jealousy on their part of his financial coups, but there is also a genuine distaste among most grandmasters for the glitzy Kasparov/Page double act.

Kasparov himself has a good answer when he is told that he is not too popular with his 'colleagues'. 'This is normal,' he says. 'The world champion is never popu- lar with other players, because he has got what they want.' Since Kasparov is still only 25, it seems that he has every chance of remaining unpopular with his rivals well into the next century.

°Forgive us our alleged trespasses.'

Previous page

Previous page