ARTS

Exhibitions

At the shallow end

Giles Auty

David Hockney: a Retrospective (Tate Gallery, till 3 January) David Hockney: a Retrospective (Tate Gallery, till 3 January)

In the mid-Sixties the young David Hockney must have reflected at times on how easily fame and comparative fortune had come his way. The work with which he first achieved prominence was hardly pro- found and was characterised, above all, by a somewhat self-conscious stylishness. Sty- lishness is what often redeems early and middle-period Hockney, yet is simul- taneously a shield and a shortcoming. It is a quality found widely also among leading illustrators and graphic designers. Once developed, it allows effects to be achieved with an apparent effortlessness and abs- ence of agonising, yet stylishness can also mask inadequate drawing and understand- ing of the seen. It is very widely believed that Hockney is a masterly draughtsman. Most of my critical colleagues state this with certainty and the view also has the status of gospel among collectors. This is a major but rather debatable claim and one which the present retrospective exhibition gives us a chance to judge fairly. Where is the evidence of this mastery and with what other artists should we compare him?

Early Hockney paintings from 1960 and 1961 have a graffiti-like spontaneity which owes much to the influence of Dubuffet. Many possess some degree of informal charm even for those without an obsessive interest in homosexual relationships. The work which followed developed and im- proved upon this canon. By 1964, the 26-year-old artist was in California. In the words of his friend and Royal College colleague R.J. Kitaj , 'His romance with LA was about two things. Los Angeles was "elsewhere", about as unlike England as a place could be, and, as his friend Isher- wood said about Berlin, Los Angeles meant boys. Together those things spelled romance . . .

A number of the better-known paintings which follow feature the putative romance of poolside and shower-room, but does `Two Boys in a Pool, Hollywood' of 1965 presage any burgeoning mastery? Rather the reverse, I would say, yet the artist grew steadily in confidence and pictorial ability nevertheless. 'Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool' of 1966 and 'A Bigger Splash' of 1967 lift this particular form of stylish image- making and witty observation to a some- what higher plane, but much of the subse- quent popularity of the pool paintings derives simply from their hedonistic sub-

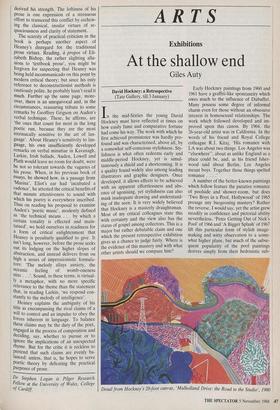

Detail from Hockney's 20-foot canvas, 'Mulholland Drive: the Road to the Studio', 1980 ject matter. However, by 1971 the artist was trying his hand at a more direct realism in 'Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)'. But here and in 'Le Parc des Sources, Vichy' of the previous year, the going had become tougher as a consequ- ence. Trees and wooded slopes are not this particular artist's forte and refused re- solutely to succumb to simple, stylistic formularisations.

David Hockney appears to be better at coming to terms with inanimate objects, preferably indoors. Simple, recessive space does not always work in his paintings, even when intended to. Let your gaze wander beyond the windows in 'Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy' from 1970-71, or in 'Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott' of 1969. How unconvincing these outdoor worlds are compared with that painted by Lucian Freud in his great double portrait of 1984-85, 'Two Irishmen in W11'. Hockney himself admits the failure: 'From 1969 to 1972 or so . . . I did a number of paintings in a naturalistic style with a very clear one-point perspective . . . . What I wanted to do, what I was struggling to do, was to make a very clear space, a space you felt clear in . . . . Well, I just couldn't achieve that clarity frankly; it was a hopeless struggle . . .

Not having overcome this particular hurdle, the artist has concentrated subse- quently on different forms of space both through photography and frequent invoca- tions of the Cubism of Picasso. Most hold that all representation of the seen is dishonest to some extent and Hockney seems obsessed unnecessarily with this issue. One presumes he chose to be an artist rather than an opthalmist. The artist has so often — on the whole, successfully — been involved in stage design and other projects over the past 15 years that paint- ing has seldom taken absolute precedence. Yet, like many before him who have acquired wealth and popular acclaim, Hockney appears concerned increasingly now about how his art will be perceived in a more serious and long-term context. In the predominantly gloomy artistic climate of the past 30 years, Hockney has been notable for his endearing panache which may even invite rather unwise comparisons to be made with French painting of the inter-war years. But Hockney's bright, increasingly lurid palette falls far short of the subtlety of Matisse, who was a consum- mate colourist. Nor, to make a less obvious but no less valid comparison, does Hock- ney have the brio and deftness of touch of Raoul Dufy, who was a draughtsman of genuine accomplishment. An even less remarked-on shortcoming in Hockney is a general absence of poetry; indeed, 'Iowa' 1964 and 'Mt Fuji and Flowers' from 1972 are lyrical rarities. On the whole, the artist's pictorial cleverness is calculated rather than inspired.

What are we to make of the most recent paintings? The 20-foot 'Mulholland Drive: the Road to the Studio' seems muddled in intention and execution, and a wall of recent portraits appears simply clumsy and unappealing. Hockney remains a talented and versatile artist but his reputation, as a painter alone, rests on rather dubious ground. The glare of publicity which has surrounded him for 25 years should not blind us to the fact that the splash he has made so far has been some distance still from the deep end of the pool.

'Believe me, Job, I know just how you feel.'

Previous page

Previous page