`I PINCH MYSELF FROM TIME TO TIME'

Christopher Fildes meets Martin Taylor, the

Mandarin-speaking ex-journalist, who has run Barclays Bank for a year (since he was 41)

THE JOB specification said it all: 'Family bank seeks non-family chap. This is a large and well-established commercial bank which, five years ago, extracted £1 billion of new capital from its shareholders, to support unspecified plans for expansion. This capital is now supporting a wide range of assets, whose performance varies, where it exists at all. They include a new head office, in the Moorish style, largely surplus to the bank's requirements. Earn- ings have turned negative and so have the shareholders. The successful candidate will be expected to sort all this out. Candi- dates with no experience of the bank's home market will be considered, and so will candidates with no experience of banking at all. It is thought that the change will be refreshing. Full benefits, stock options and about £500,000 a year.'

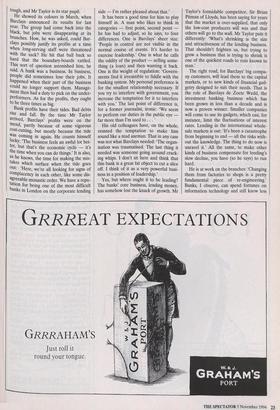

I admit to having drafted that version myself at the time, and the headhunters at Spencer Stuart may have put it differently, but this was what they had to do for Bar- clays, and the man they found was Martin Taylor. It is just a year since he turned up at Royal Mint Court, the elegant head office which has now been relegated, as Barclays' newest director and, at 41, its next chief executive. 'I pinch myself from time to time,' he says.

Well might he. Here was Barclays, accus- tomed to primacy as Britain's biggest bank- ing group, with the widest international reach: a world-league business. Knocked off the top spot at home by National West- minster, Barclays had come back aggres- sively, under the slogan: 'Number One by '91'. A City poet later added: 'In the pooh by'92'. Barclays went in deep. The recession caught the bank over-extended, with heavy loans against ambitious property develop- ments — Canary Wharf was only the most visible. It found that it had inadvertently collected a portfolio of country house hotels and putative golf courses. Abroad, in America, France and the Virgin Islands (of all places) it faced losses which would swal- low the billion that its shareholders had put up. Barclays went into the red and cut its dividend.

That was one sure way to catch the shareholders' attention. Barclays found another when the new chairman, Andrew Buxton, proposed to double up as chief executive — tut, tut, a breach of Sir Adrian Cadbury's code. Rumbles among the big share-owning institutions were echoed in the boardroom. In the end, five knighted directors were sent out on a quest to find a chief executive. This was something new. Barclays was accustomed to chairmen from among its founding families and to general managers who had come up through the ranks. Now the knights' quest took their headhunters far and wide — to bankers in America and to ice-cream specialists at Unilever. They found their man at Cour- taulds Textiles.

Born in Burnley in 1952, Martin Taylor might have made his own way to the cotton trade. In fact he took the long way round, by way of scholarships to Eton and Balliol (he read Mandarin Chinese) and a job on, the Lax column of the Financial Times, tried to recruit him out of that, but Sir Christopher Hogg of Courtaulds (and now, Reuters) got there first. The Hogg school of management is serious, thoughtful and tough, and Mr Taylor is its star pupil. He showed its colours in March, when Barclays announced its results for last year. The group had come back into the black, but jobs were disappearing at its branches. How, he was asked, could Bar- clays possibly justify its profits at a time when long-serving staff were threatened with the sack? He hit that ball back so hard that the boundary-boards rattled. This sort of question astonished him, he said. A bank was a business. In business, people did sometimes lose their jobs. It happened when their part of the business could no longer support them. Manage- ment then had a duty to pick on the under- performers. As for the profits, they ought to be three times as big. Bank profits have their tides. Bad debts rise and fall. By the time Mr Taylor arrived, Barclays' profits were on the mend, partly because of some vigorous cost-cutting, but mostly because the tide was coming in again. He counts himself lucky: 'The business feels an awful lot bet- ter, but that's the economic cycle — it's the time when you can do things.' It is also, as he knows, the time for making the mis- takes which surface when the tide goes out: 'Here, we're all looking for signs of complacency in each other, like some dis- agreeable monastic order. We have a repu- tation for being one of the most difficult banks in London on the corporate lending side — I'm rather pleased about that.'

It has been a good time for him to play himself in. A man who likes to think in categories — first point, second point he has had to adjust, so he says, to four differences. One is Barclays' sheer size: `People in control are not visible in the normal course of events. It's harder to exercise leadership.' One is what he calls the oddity of the product — selling some- thing (a loan) and then wanting it back. One is the weight of regulation: 'Govern- ments find it irresistible to fiddle with the banking system. My personal preference is for the smallest relationship necessary. If you try to interfere with government, you increase the temptation for it to interfere with you.' The last point of difference is, for a former journalist, ironic: 'We seem to perform our duties in the public eye far more than I'm used to . . . '

His old colleagues have, on the whole, resisted the temptation to make him sound like a mad axeman. That in any case was not what Barclays needed: The organ- isation was traumatised. The last thing it needed was someone going around crack- ing whips. I don't sit here and think that this bank is a great fat object to cut a slice off. I think of it as a very powerful busi- ness in a position of leadership.'

Yes, but where ought it to be leading? The banks' core business, lending money, has somehow lost the knack of growth. Mr Taylor's formidable competitor, Sir Brian Pitman of Lloyds, has been saying for years that the market is over-supplied, that only the low-cost producers will win and that others will go to the wall. Mr Taylor puts it differently: 'What's shrinking is the size and attractiveness of the lending business. That shouldn't frighten us, but trying to grow a business that is trying to shrink is one of the quickest roads to ruin known to man.'

The right road, for Barclays' big compa- ny customers, will lead them to the capital markets, or to new kinds of financial gad- getry designed to suit their needs. That is the role of Barclays de Zoete Wedd, the investment banking business which has been grown in less than a decade and is now a proven winner. Smaller companies will come to use its gadgets, which can, for instance, limit the fluctuations of interest rates. Lending in the international whole- sale markets is out: 'It's been a catastrophe from beginning to end — all the risks with- out the knowledge. The thing to do now is unravel it.' All the same, to make other kinds of business compensate for lending's slow decline, you have (so he says) to run hard.

He is at work on the branches: 'Changing them from factories to shops is a pretty fundamental piece of re-engineering.' Banks, I observe, can spend fortunes on information technology and still know less and less about their customers. Mr Taylor takes the point: 'We're using technology to re-personalise the bank.' His systems will, he hopes, restore to his managers the information which used to reach them in the old days, when they would arrive in the mornings and settle down with dawning horror to read their customers' cheques. Pay the Ritz Hotel, Paris? How much? What for? I'm sure he'll tell me there's been some mistake, but I want this cus- tomer to come in and see me.

Barclays itself needed to change shape. It was like a country house, with an origi- nal core block — the High Street bank and all sorts of estate offices and stables and conservatories, tacked on over the years. The house, Mr Taylor thinks, has got muddled up with the estate. Good structures of management, he notes, can- not do your work for you, but bad ones can get in the way. He is trying to move towards less rigid structures, with fewer layers of managers, but it is a continuous process: 'Organisation and management changes should be reasonably small and made reasonably often. It's not like the Treaty of Versailles, where you redraw the boundaries. I don't think it'll ever be fin- ished, really.'

At Barclays Mr Taylor has fences to mend, or to rebuild from the ground up. He lists three relationships — In order of ease of access: shareholders, staff, cus- tomers. We did fall out with all three, which was quite unusual. To fall out with one, seriously, risks the foundation of the business.'

The shareholders helped to install him, and he knows what they want: perfor- mance, and fewer unpleasant surprises. `We have to convince them we're looking after their money properly.' The staff, he says, are under enormous pressure: `They're working very hard and they won- der if people have noticed.' The idea that banking should be a job for life still lingers. `So,' I ask, 'you cannot tell them that the bad news about jobs is all over?' `Well,' he says, 'I don't think in the real world you can ever say that.'

Hardest of all to reach are the cus- tomers: 'Most of them feel indifferent about their banking relationships. Those who do feel unhappy are very unhappy indeed. It's a shame, and a great public relations disaster. Some of them just ran out of money, some of them have been roughly treated.' A bank trains its staff to be careful with money, and some of them can overdo it, but the risks are there: `What worries me very much is a feeling among small business people that it's OK not to pay the bank back — the idea that the money we lend is not the same as the money we take on deposit.'

`Well, what's on your agenda for today?' A bank and its customers meet on both sides of its balance-sheet. When that rela- tionship works it can be a partnership that lasts a lifetime. When it doesn't, the part- nership can be as successful and durable as the Prince of Wales's marriage, and leave the same feelings behind it. Mr Taylor believes that the banks have a job of rebuilding to do: 'Rebuilding their moral authority and reputation. It's not about superficial things. It's about reputation and not about image. You do it brick by brick.'

The knights were right: the change is refreshing. I ask Mr Taylor if he is enjoying himself. I'm beginning to,' he says, 'in the last couple of months. It's beginning to feel familiar — I hope in a good sense. There's a narrow line between two great dangers. One is rejection — they spit you out — and one is absorption. If you're absorbed you become indistinguishable from the rest of the business.' I do not foresee it.

Previous page

Previous page