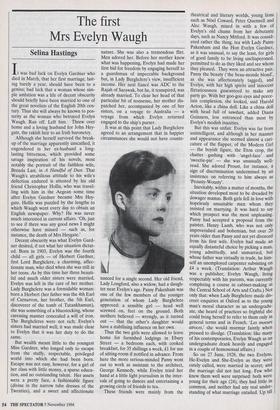

The first Mrs Evelyn Waugh

Selina Hastings

It was bad luck on Evelyn Gardner who died in March, that her first marriage, last- ing barely a year, should have been to a genius; bad luck that a woman whose sim- ple ambition was a life of decent obscurity should briefly have been married to one of the great novelists of the English 20th cen- tury. Thus she will always be known to pos- terity as the woman who betrayed Evelyn Waugh. Ran off. Left him. Threw over home and a loving husband for John Hey- gate, the rakish heir to an Irish baronetcy.

Although she herself survived the break- up of the marriage apparently unscathed, it engendered in her ex-husband a long- lasting bitterness, which provided some savage inspiration of his novels, most notably the portrait of the faithless wife, Brenda Last, in A Handful of Dust. That Waugh's atrabilious attitude to his wife's defection endured is attested by his old friend Christopher Hollis, who was travel- ling with him in the Aegean some time after Evelyn Gardner became Mrs Hey- gate. Hollis was puzzled by the lengths to which Waugh went every day to obtain an English newspaper. Why? He was never much interested in current affairs. 'Oh, just to see if there was any good news I might otherwise have missed — such as, for instance, the death of Mrs Heygate.'

Decent obscurity was what Evelyn Gard- ner desired, if not what her situation dictat- ed. Born in 1903, Evelyn was the fourth child — all girls — of Herbert Gardner, first Lord Burghclere, a charming, affec- tionate man, who died when she was still in her teens. As by this time her three beauti- ful and much older sisters were married, Evelyn was left in the care of her mother. Lady Burghclere was a formidable woman: born a Herbert (her father was the 4th Earl of Camarvon, her brother, the 5th Earl, discoverer of the tomb of Tutankhamun), she was something of a bluestocking, whose caressing manner concealed a will of iron. The Burghcleres were not rich; Evelyn's sisters had married well; it was made clear to Evelyn that it was her duty to do the same.

But wealth meant little to the youngest Miss Gardner, who longed only to escape from the stuffy, respectable, privileged world into which she had been born. Escape was not easy, however, for a girl of her class with little money, a sparse educa- tion, and no outstanding talent. Her assets were a pretty face, a fashionable figure (divine in the narrow tube dresses of the Twenties), and a sweet and affectionate nature. She was also a tremendous flirt. Men adored her. Before her mother knew what was happening, Evelyn had made her first bid for freedom by engaging herself to a guardsman of impeccable background but, in Lady Burghclere's view, insufficient income. Her next fiancé was ADC to the Rajah of Sarawak, but he, it transpired, was already married. To clear her head of that particular bit of nonsense, her mother dis- patched her, accompanied by one of her sisters, on a voyage to Australia — a voyage from which Evelyn returned engaged to the ship's purser.

It was at this point that Lady Burghclere agreed to an arrangement that in happier circumstances she would not have counte- nanced for a single second. Her old friend, Lady Longford, also a widow, had a daugh- ter near Evelyn's age. Pansy Pakenham was one of the few members of the younger generation of whom Lady Burghclere approved: a sensible girl — head well screwed on, feet on the ground. Both mothers believed — wrongly, as it turned out — that the other's daughter would have a stabilising influence on her own.

Thus the two girls were allowed to leave home for furnished lodgings in Ebury Street — a bedroom each, with cooked breakfast, for 35 shillings a week, £1 for use of sitting-room if notified in advance. From here the more serious-minded Pansy went out to work as assistant to the architect, George Kennedy, while Evelyn tried her hand at a little light journalism in the inter- vals of going to dances and entertaining a growing circle of friends to tea.

These friends were mainly from the theatrical and literary worlds, young lions such as Noel Coward, Peter Quennell and Alec Waugh, mixed in with a few of Evelyn's old chums from her debutante days, such as Nancy Mitford. It was consid- ered rather the thing, tea with Lady Pansy Pakenham and the Hon Evelyn Gardner, as it was unusual, to say the least, for girls of good family to be living unchaperoned, permitted to do as they liked and see whom they pleased. They were an attractive pair, Pansy the beauty (`the beau-monde blond', as she was affectionately tagged), and Evelyn, with her high spirits and innocent flirtatiousness guaranteed to make any party go. With her goo-goo eyes and porce- lain complexion, she looked, said Harold Acton, like a china doll. Like a china doll with head full of sawdust, added Diana Guinness, less entranced than most by Evelyn's modish inanities.

But this was unfair. Evelyn was far from unintelligent, and although in her manner and appearance she seemed almost a cari- cature of the flapper, of the Modern Girl — the boyish figure, the Eton crop, the chatter gushing with 'angel-face' and `sweetie-pie' — she was unusually well- read. She adored Proust, for instance, a sign of discrimination undermined by an insistence on referring to him always as `Prousty-Wousty'.

Inevitably, within a matter of months, the situation developed most to be dreaded by dowager mamas. Both girls fell in love with hopelessly unsuitable men whom they insisted on marrying. It was hard to say which prospect was the most unpleasing. Pansy had accepted a proposal from the painter, Henry Lamb, who was not only impoverished and bohemian, but over 20 years older than Pansy and not yet divorced from his first wife. Evelyn had made an equally distasteful choice by picking a man, young admittedly, and unmarried, but whose father was virtually in trade, he him- self an unemployed carpenter subsisting on £4 a week. (Translation: Arthur Waugh was a publisher; Evelyn Waugh, living respectably with his parents, was currently completing a course in cabinet-making at the Central School of Arts and Crafts.) Not only that: when Lady Burghclere made dis- creet enquiries at Oxford as to the young man's moral character as an undergradu- ate, she heard of practices so frightful she could bring herself to refer to them only in general terms and in French. 'Les moeurs atroces,' she would murmur faintly when pressed to divulge. (Translation: like many of his contemporaries, Evelyn Waugh as an undergraduate drank heavily and engaged in a couple of homosexual affairs.) So on 27 June, 1928, the two Evelyns, He-Evelyn and She-Evelyn as they were cutely called, were married in secret; and the marriage did not last long. Few who knew them well were surprised: both were young for their age (24), they had little in common, and neither had any real under- standing of what marriage entailed. Up till now Evelyn Gardner's relationships had been as effortlessly ended as begun. `[She] had immense charm and a very generous nature,' said one acquaintance, 'but she was essentially light.' Although later she became a model wife and mother, showing an unsuspected gift for domesticity, at this stage she was more interested in having fun, as far as possible from the basilisk eye of Lady Burghclere, than in settling down. And Evelyn Waugh, busy pursuing his liter- ary career, was not often around to have fun with, disappearing for weeks at a time to write, leaving his wife on her own in their tiny flat in Canonbury. Naturally, kind men friends took pity on her, escorting her to dinner, to nightclubs and parties. And one of these friends was John Heygate.

Heygate was handsome, affable and highly-strung, the son of an Eton beak, a dry stick of a man, so deeply conventional that `Doing a Heygate' became the phrase for doing the most conventional thing. His mother was descended from the diarist, John Evelyn, and Heygate himself only just escaped being named 'Evelyn' after him which would have turned an already con- fusing situation into one bordering on farce. At the time he met Evelyn Gardner, Heygate, having failed for the Diplomatic Service, was working as a news editor at the BBC, a job from which he soon resigned, fully aware that in no circum- stances would the puritanical Lord Reith tolerate an adulterer on his staff. Although Evelyn Gardner may have married the first time more for contingency than for love, there is no doubt that she fell very much in love with John Heygate. 'She couldn't take her eyes off him,' said the friend of both, Anthony Powell. 'She was madly in love with him, jealous if he even looked at another woman.'

For a while, the couple lived together in the flat in Canonbury Square. Then after one or two half-hearted attempts at recon- ciliation, Waugh agreed to a divorce, and in 1930 Evelyn and Heygate were married. (Anthony Powell in his novel Agents & Patients used the Heygates as the model for that gipsyish couple, the Maltravers). They soon moved out of London and into a series of rented cottages in Sussex where Heygate earned a meagre living as a writer, publishing a novel about Eton, Decent Fellows, very much along the lines of Alec Waugh's sensational (for those days) novel about Sherbome, The Loom of Youth. Their income was modestly supple- mented by Evelyn's journalism, unambi- tious little articles for Harper's Bazaar. But in spite of lacking any notable talent in this direction, in another Evelyn came very much into her own, on little money creat- ing in those damp, pokey little houses a pretty and comfortable domestic environ- ment. And at first they enjoyed themselves, with Heygate much of the day cheerfully drunk, the two of them sharing a passion for fast cars and speedway (motor cycle) racing. Eventually Heygate landed a job writing scripts for a German film company, which involved a move to Berlin. But by this time both had got bored with the marriage, and although Evelyn went to Germany more than once to visit her husband, they were amicably divorced in 1936.

As before, Evelyn did not dwell on her failure. Soon after the decree came through, she was heard to say meditatively, `Do you know, if Evelyn Waugh were to walk into this room, I wouldn't recognise him. And I'm sure it'll soon be the same with John.'

Evelyn moved to another cottage, at Matfield in Kent, from where the following year she married again. Ronald Nightingale was a Tunbridge Wells estate agent, and by him Evelyn had two children, Virginia, who until recently worked in the Chelsea Physic Garden, and Benedict, now theatre critic of the Times. Nightingale, a rather silent, surly figure, was a conscientious father and hus- band, until he fell in love with somebody else; and in 1955 Evelyn's third and last marriage came to an end. Her remaining years — which were many: she was 90 when she died — should have been tranquil. She loved her Sussex cottages, the one in Cuckfield, outside Haywards Heath, and then Orchard Cot- tage in Cross Lane, near Wadhurst; and she loved the safe, undemanding life of the village, visited often by her children and by other members of her large family.

then at the end of her life, the fame of that first husband, a man by her virtually forgotten, began to swell and grow like a deadly toadstool, the full poisonous horror of it finally exploding in the dramatisation for television of Brideshead Revisited.

Almost overnight, the very private. Mrs Nightingale found herself the focus of attention from television crews and jour- nalists, from literary biographers and Ph.D. students from all over the world. Outraged at the violation of her treasured anonymity, she was appalled, hated it, refused to see any of them. More and more she began to complain of a pervading sense of persecu- tion, which, she said, was ruining her life.

But why did she loathe it quite so much? The answer, it appears, is a feeling of guilt. As the years passed, Evelyn Gardner start- ed to be tormented by her conscience, not for leaving Waugh, but for leaving Waugh with such a legacy of bitterness. The more she heard and read about her first hus- band, the more she was convinced that it As on her account that Waugh had devel- oped into such a monster. Had she stayed with him, the delightful young man she married would have aged calmly into a delightful old man: that choleric, diabolic, cigar-puffing dragon, on record as the nastiest-tempered man in England, would never have come into being. It was all her fault.

Selina Hastings' biography of Evelyn Waugh is published by Sinclair-Stevenson at £20.

Previous page

Previous page