THE FREE SUBSCRIBER

John Simpson recalls his

correspondence with Roger Cooper from prison in Teheran

EACH week's mail at Evin prison in Teheran, a place with an evil reputation, includes a large buff envelope with a familiar feel to it: The Spectator has arrived at perhaps the most unlikely address on earth. It's always late, of course, often by several weeks. Someone has examined it, to see it doesn't contain anything defama- tory of Islam, or anything indecent pictures of women with naked hair, for instance. As for the prisoner to whom the subscription is directed, he opens it with particular enthusiasm, since it is his main link with the world outside the prison walls. Or at least it was: in the early hours of Tuesday 2 April, the most famous Spectator reader in captivity was released. After five and a quarter years, Roger Cooper was a free man at last. To me, however, Roger was, in a sense, a free man even in his prison cell. His letters, painstakingly written in capitals so the censor could see they contained no funny business, spoke of the birds he had spotted (`sparrow, wagtail, two species of pigeon, rook and hooded crow . . . . I did once hear the ring-necked parakeet that used to visit my downtown garden in the old days') and included elaborate ana- grams on the names of his friends and of leading figures in the British government: `Who "should guard" [Douglas Hurd] Brit- ish interests abroad? His predecessor may have made some mistakes but the hard-line Russian diplomat who said of him, "Goofed why is free?" [Sir Geoffrey Howe] surely takes the iron-like reputation of "that great charmer" [Margaret Thatcher] too literally.' But, says the same letter, 'Lately I've been less frivolous with my time and devote myself to English and Russian fiction, and whatever French, German and Spanish books come my way, plus three Persian newspapers a day and their cross- words.'

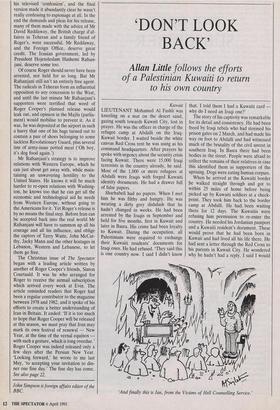

Knowing the sensitivities of the Iranian clerical mind my girlfriend and I, having decided we should send Roger some car- toons, settled on the work of the Amer- ican, Gary Larson. He peoples American suburbia with human-like cockroaches, elephants, lions and snakes who wear Western clothes and (in the case of the females) elaborate diamante glasses. We reasoned that no censor could object to a female cockroach which displayed its un- covered hair. And so it proved. 'The three Larson collections arrived back in August . . . At first I didn't think I liked Larsonry v. much but it grows on you, and I think the colour helps. My cell-mates including two Americans were v. appreciative ("at last Cooper has got something worth read- ing").' We also sent him a postcard with a Larson cartoon of two dogs watching their mistress dishing out tinned meat into their bowls and saying, 'Oh boy, it's dog food again.' Prisoners will quarrel about any- thing and in fact the card led to a huge row about whether the dogs really liked dog- food again! I was sure they didn't, but I suppose it's funny either way. There were echoes for us . . .

For most people, I suppose, there isn't much to choose between Iran and its difficult neighbour, Iraq. Having spent some time in both countries, I find the differences highly instructive. The treat- ment in jail of two of my friends, both accused of espionage and both innocent, demonstrates some of them. Last year Farzad Bazoft was plainly tortured before he confessed on television to spying, and then he was executed because Saddam Hussein was irritated by the way people demanded his freedom. Roger Cooper wasn't tortured (though he was knocked about at first in the usual Middle Eastern fashion) and he wasn't executed because Iran isn't a dictatorship but — within narrow limits — an odd kind of democracy. He negotiated with his interrogators for a long time about the words he should use in `Sure I was relieved. But then I started thinking, "Why did he throw me back?" ' his televised 'confession', and the final version made it abundantly clear he wasn't really confessing to espionage at all. In the end the demands and pleas for his release, many of them made with the advice of Mr David Reddaway, the British chargé d'af- faires in Teheran and a family friend of Roger's, were successful. Mr Reddaway, and the Foreign Office, deserve great credit. The Iranian government, led by President Hojetoleslam Hashemi Rafsan- jani, deserve some too.

Of course Roger should never have been arrested, nor held for so long. But Mr Rafsanjani still isn't an entirely free agent. The radicals in Teheran form an influential opposition to any concession to the West, and until the last minute Mr Rafsanjani's supporters were terrified that word of Roger Cooper's planned release would leak out, and opinion in the Majlis (parlia- ment) would mobilise to prevent it. As it was, he was deposited at the airport in such a hurry that one of his bags turned out to contain a pair of shoes belonging to some luckless Revolutionary Guard, plus several tins of army-issue potted meat (`Oh boy, it's dog food again.') Mr Rafsanjani's strategy is to improve relations with Western Europe, which he can just about get away with, while main- taining an unwavering hostility to the United States. He knows it will be much harder to re-open relations with Washing- ton, he knows too that he can get -all the economic and technological aid he needs from Western Europe, without going to the Americans for it. Yet Roger's release is by no means the final step. Before Iran can be accepted back into the real world Mr Rafsanjani will have to summon up all his courage and all his influence, and oblige the captors of Terry Waite, John McCar- thy, Jacky Mann and the other hostages in Lebanon, Western and Lebanese, to let them go free.

The Christmas issue of The Spectator began with a leading article written by another of Roger Cooper's friends, Simon Courtauld. It was he who arranged for Roger to receive the airmail subscription which arrived every week at Evin. The article reminded readers that Roger had been a regular contributor to the magazine between 1978 and 1982, and it spoke of his efforts to create a better understanding of Iran in Britain. It ended: 'If it is too much to hope that Roger Cooper will be released at this season, we must pray that Iran may mark its own festival of renewal — New Year, at the time of the vernal equinox with such a gesture, which is long overdue.' Roger Cooper was indeed released only a few days after the Persian New Year. `Looking forward,' he wrote to me last May, `to accepting your invitation to din- ner one fine day.' The fine day has come. See also page 22.

John Simpson is foreign affairs editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page