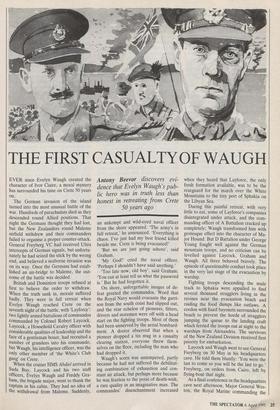

THE FIRST CASUALTY OF WAUGH

Antony Beevor discovers evi- dence that Evelyn Waugh's pub- lic hero was in truth less than honest in retreating from Crete

50 years ago

EVER since Evelyn Waugh created the character of Ivor Claire, a moral mystery has surrounded his time on Crete 50 years on.

The German invasion of the island turned into the most unusual battle of the war. Hundreds of parachutists died as they descended round Allied positions. That night the Germans thought they had lost, but the New Zealanders round Maleme airfield withdrew and their commanders failed to organise a proper counter-attack. General Freyberg VC had received Ultra intercepts of German signals, but unfortu- nately he had seized the stick by the wrong end, and believed a seaborne invasion was on its way. Once the Germans had estab- lished an air-bridge to Maleme, the out- come of the battle was decided.

British and Dominion troops refused at first to believe the order to withdraw. When the truth sank in, morale suffered badly. They were in full retreat when Evelyn Waugh reached Crete on the seventh night of the battle, with `Layforce': two lightly armed battalions of commandos commanded by Colonel Robert Laycock. Laycock, a Household Cavalry officer with considerable qualities of leadership and the face of a gentleman boxer, had recruited a number of grandees into his commando, but Waugh, his intelligence officer, was the only other member of 'the White's Club gang' on Crete.

When the cruiser HMS Abdiel arrived in Suda Bay, Laycock and his two staff officers, Evelyn Waugh and Freddy Gra- ham, the brigade major, went to thank the captain in his cabin. They had no idea of the withdrawal from Maleme. Suddenly, an unkempt and wild-eyed naval officer from the shore appeared. 'The army's in full retreat,' he announced. 'Everything is chaos. I've just had my best friend killed beside me. Crete is being evacuated!'

`But we are just going ashore', said Graham.

`My God!' cried the naval officer. `Perhaps I shouldn't have said anything.' `Too late now, old boy', said Graham. `You can at least tell us what the password is.' But he had forgotten it.

On shore, unforgettable images of de- feat greeted the commandos. Word that the Royal Navy would evacuate the garri- son from the south coast had slipped out, and the rear echelon of pioneers, fitters, drivers and storemen were off with a head start on the fighting troops. Most of them had been unnerved by the aerial bombard- ment. A doctor observed that when a pioneer dropped a tin mug in a casualty clearing station, everyone threw them- selves on the floor, including the man who had dropped it.

Waugh's scorn was untempered, partly because he had not suffered the debilitat- ing combination of exhaustion and con- stant air attack, but perhaps more because he was fearless to the point of death-wish, a rare quality in an imaginative man. The commandos' disenchantment increased when they heard that Layforce, the only fresh formation available, was to be the rearguard for the march over the White Mountains to the tiny port of Sphakia on the Libyan Sea.

During this painful retreat, with very little to eat, some of Layforce's companies disintegrated under attack, and the com- manding officer of A Battalion cracked up completely; Waugh transformed him with grotesque effect into the character of Ma- jor Hound. But D Battalion under George Young fought well against the German mountain troops, and no criticism can be levelled against Laycock, Graham and Waugh. All three behaved bravely. The episode of questionable conduct took place in the very last stage of the evacuation by warship.

Fighting troops descending the mule track to Sphakia were appalled to find several thousand stragglers living in the ravines near the evacuation beach and raiding the food dumps like outlaws. A cordon with fixed bayonets surrounded the beach to prevent the horde of stragglers jumping the queue to the landing craft which ferried the troops out at night to the warships from Alexandria. The survivors of the New Zealand Division received first priority for embarkation.

Laycock and Waugh went to see General Freyberg on 30 May in his headquarters cave. He told them bluntly: 'You were the last to come so you will be the last to go.' Freyberg, on orders from Cairo, left by flying-boat that night. At a final conference in the headquarters cave next afternoon, Major General Wes- ton, the Royal Marine commanding the rearguard, announced that this would be the last night of evacuation. He repeated Freyberg's instruction that Layforce could only embark after 'other fighting forces' and ordered Colonel Laycock to conduct the surrender next morning.

Probably at about eight o'clock that evening Laycock, accompanied by Waugh, buttonholed General Weston. According to Laycock's version, an unnamed staff officer — almost certainly Waugh pointed out that `Laycock still had two battalions of his brigade in Egypt'. Weston agreed to let him leave.

At about nine o'clock, Freddy Graham, Laycock's brigade major, reached the headquarters cave in answer to a sum- mons. General Weston called him in and dictated the order for surrender, which was now to be handled by the officer who had cracked up. 'Well, gentlemen,' Weston said before walking down the hill to his Sunderland flying-boat, 'there are one million drachmae in that suitcase, there's a bottle of gin in the corner, goodbye and good luck.'

Shortly after General Weston's depar- ture, Laycock appeared. He told the de- jected Graham about the staff officer's intervention, then claimed that Weston had added: 'You and your staff and as many of your troops as you can get away must go tonight — my staff will see to it.' Waugh makes no mention anywhere of this remark nor of the nameless staff officer. While one can understand General Weston allowing Laycock to leave, it is hard to see him allowing Layforce to jump the queue in front of his own Marine battalion and the two Australian battalions.

Graham, thoroughly elated by Laycock's announcement, never thought to disbe- lieve his admired brigade commander, either then or later. 'We never even knew,' he wrote in 1948, 'who the staff officer was to whom we owed our deliverance.' Waugh said nothing.

Laycock gathered up any commandos he could find, and they made their way down to the beach. Of the two Australian batta- lions, one was already in the queue, the other had not yet arrived. Nor had General Weston's battalion of Marines. Laycock and Waugh cannot have forgotten them since Waugh recorded that around dusk `there was some firing inland where the Marines held a line'.

At around 11, Laycock sent Waugh's soldier servant, Private Tanner, up the ravine to George Young's battalion to bring them down too. But they were too dispersed to reach the beach in time. When Tanner returned, Laycock and Waugh were already ensconced on a destroyer. Tanner was one of the last off.

Waugh, presumably on Laycock's direc- tion, wrote in the Layforce war diary:

On finding that entire staff of Creforce [General Weston] had embarked, in view of fact that all fighting forces were now in position for embarkation and that there was no enemy contact, Col. Laycock on own authority issued orders to Lt. Col. Young to lead troops to Sphakion by route avoiding the crowded main approach to town and to use his own personality to obtain priority laid down in Div. orders.

It would have been hard to compress more distortions of the truth into a single sentence. The most serious was 'all fighting forces were now in position for embarka- tion' since neither the Australian 2/7th Battalion nor the Marines had then reached the beach. Both had priority over Layforce, which should have held its posi- tions until after their embarkation.

Nothing is said of Laycock's story to Graham that Weston was allowing Layforce off early; instead Laycock takes that decision 'on his own authority' in direct contravention of both Freyberg and Weston's orders that Layforce was `to cover withdrawal of other fighting forces'.

The claim of `no enemy contact' was also misleading with the beach-head sur- rounded by mountain troops. One detach- ment had already penetrated the Sphakia gorge where it was dealt with by Charles Upham's platoon of New Zealanders, an exploit which contributed to the first of his two Victoria Crosses. And even Waugh `Come on guys! I can't run in these — they're my trainers.' recorded the Marines' firefight at dusk.

The Australian 2/7th Battalion, which arrived after midnight, shuffled patiently forwards in the queue unaware that over 200 men from Layforce had slipped in ahead of them. 'Then came the greatest disappointment of all,' their second-in- command wrote later in prison camp, 'the sound of anchor chains through the hawse.'

There can be little doubt that Waugh felt deeply unsettled by the episode. He rightly admired Laycock for his bravery and lead- ership in battle, and must have agreed passionately that it was futile to become prisoners of war. Yet there was no disguis- ing the fact that Laycock had tried to take as many of his men as he could to justify his own legitimate, but not creditable depar- ture. Although little is revealed by the very controlled tone of Waugh's personal account, which has many omissions, Laycock's lies, first to Graham and then to others afterwards, must have troubled his conscience.

Waugh's experience, and his consequent disillusionment which had a strong streak of self-disgust, seem to have constituted something of a crossroads in his own life, as well as in that of his fictional alter ego, Guy Crouchback. In Officers and Gentle- men, a number of events are reshuffled to comply with certain moves away from real characters, yet the moral unease remains. While Waugh, the keeper of the Layforce war diary, made false statements in it to bury the truth, in the novel Guy Crouch- back conceals, then burns the Hookforce war diary because it alone contains the proof of Ivor Claire's dishonour in aban- doning his soldiers.

Claire, a Household Cavalry officer of great charm, is not supposed to be Laycock: he is more faithfully portrayed in the character of Tommy Backhouse, whom Waugh saves from the moral mess by having him fall down a companionway on the voyage out to Crete. Yet Ivor Claire still represents the betrayal of Waugh's infatuation with the gallant company. And although Waugh's admiration for Laycock remained an article of faith in later years, Laycock was the only other member of that group who had gone to Crete.

In June 1955, Officers and Gentlemen was published with a dedication to Laycock. On seeing this, Ann Fleming telegraphed Waugh: 'Presume Ivor Claire based Laycock dedication ironical.'

`Your telegram horrifies me,' he replied. `Of course there is no possible connection between Bob and Claire. . . . For Christ's sake lay off the idea of Bob=Claire . . . Just shut up about Laycock. Fuck you, E Waugh.' In his diary, he wrote: 'I replied that if she breathes a suspicion of this cruel fact it will be the end of our friendship.' Fact or not, the memory was clearly cruel for Waugh.

Antony Beevor's book, Crete: The Battle and Resistance, will be published on 2 May by John Murray (f19.95).

Previous page

Previous page