ARTS

Crafts

The Ditchling effect

Tanya Harrod on a unique and influential experiment in British artistic life

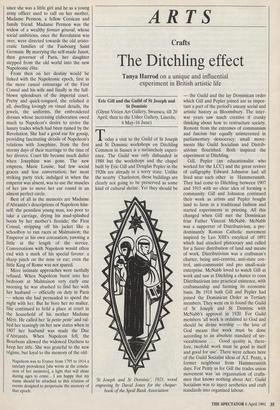

Eric Gill and the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic (Glynn Vivien Art Gallery, Swansea, till 20 April; then to the Usher Gallery, Lincoln, 4 May-16 June)

Today a visit to the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic workshops on Ditchling Common in Sussex is a melancholy experi- ence. The Guild was only disbanded in 1988 but the workshops and the chapel built by Eric Gill and Douglas Pepler in the 1920s are already in a sorry state. Unlike the nearby Charleston, these buildings are clearly not going to be preserved as some kind of cultural shrine. Yet they should be `St Joseph and St Dominic, 1921, wood engraving by David Jones for the cheque- book of the Spoil Bank Association — the Guild and the lay Dominican order which Gill and Pepler joined are as impor- tant a part of the period's uneasy social and artistic history as Bloomsbury. The inter- war years saw much creative if cranky thinking about how to restructure society. Remote from the extremes of communism and fascism but equally uninterested in parliamentary democracy, small move- ments like Guild Socialism and Distrib- utivism flourished. Both inspired the experiment at Ditchling.

Gill, Pepler (an educationalist who worked for the LCC) and the great reviver of calligraphy Edward Johnston had all lived near each other in Hammersmith. They had come to Ditchling between 1907 and 1915 with no clear idea of forming a community. Gill and Johnston continued their work as artists and Pepler bought land to farm in a traditional fashion and started experiments in printing. All this changed when Gill met the Dominican friar Father Vincent McNabb. McNabb was a supporter of Distributivism, a pre- dominantly Roman Catholic movement inspired by Leo XIII's encylical of 1891 which had attacked plutocracy and called for a fairer distribution of land and means of work. Distributivism was a craftsman's charter, being anti-centrist, anti-state con- trol, anti-communist and pro small-scale enterprise. McNabb loved to watch Gill at work and saw at Ditchling a chance to coax Distributivism into practical existence, with craftsmanship and farming its economic basis. By 1918 both Gill and Pepler had joined the Dominican Order as Tertiary members. They went on to found the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic with McNabb's approval in 1920. For Guild members 'all work is ordained to God and should be divine worship — the love of God means that work must be done according to an absolute standard of ser- viceableness . . . Good quality is, there- fore, twofold: work must be good in itself and good for use'. There were echoes here of the Guild Socialist ideas of A.J. Penty, a former neighbour from Hammersmith days. For Penty as for Gill the trades union movement was 'an organisation of crafts- men that knows nothing about Art'. Guild Socialism was to inject aesthetics and craft standards into organised labour. Eric Gill and the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic is a pleasing exhibition which looks at the craftsmanship that came out of the experiment. The title is perhaps mis- leading. Gill, though a founder, was only a Guild member for six years. And some of the most interesting figures whose work is included — for example the weaver Ethel Mairet — were part of the Sussex artistic community centred on Ditchling Common and Village but did not join the Guild. Johnston never joined because, according to Evelyn Waugh, 'he was so good and holy and odd that he never felt the need for it'. Nonetheless all the exhibits in this show books, pamphlets, metalwork, carving, toys, puppets, weaving — have a visual coher- ence based on modesty and simplicity.

Most of the Guild's work was devotional. Pepler's St Dominic Press produced mass sheets, ordination cards and ecclesiastical music. But the Press also printed and pub- lished works crucial to the craft movement of the inter-war years — Ethel Mairet's pioneering Vegetable Dyes, the first volume of Woodwork by the gentleman carpenter and tax reformer A. Romney Green and a series of Handwork pamphlets by Bernard Leach, Romney Green and Ethel and Philip Mairet. Pepler also produced an edi- tion of the cult book of the 1930s craft movement. This was Jacques Maritain's Art et Scholastique, which served to evaluate and give credibility to the combination of spirituality and manual labour which went with the Ditchling life. Gill's many direct contributions to beautifying Guild life included engravings for the St Dominic Press and a great wooden rood crucifix for the chapel. The Guild became a place of retreat for the vulnerable — men like Desmond Chute (artist and later priest in Rapallo) and the painter David Jones. But despite the intense joy the Tertiary/Guild life brought Gill at first, by 1924 he had had enough and left Ditchling with his fam- ; ily for the solitude of Wales. This was a personal blow to Pepler but it did not mean the end of the community.

Throughout the 1930s a mass of work, mainly ecclesiastical, was produced by other members. George Maxwell, a keen Distributivist, made simple oak furniture and handlooms for the growing handweav- ing movement. Dunstan Pruden — an ecclesiastical silversmith of great distinc- tion — joined the Guild in 1932. Valentine KilBride, a protégé of the eccentric Father John O'Connor of Bradford and pupil of Ethel Mairet, set up in Gill's old workshop in 1925. Together with Bernard Brockle- hurst he wove plain silk material which he had made up into vestments for the Roman Catholic clergy. They looked modern in their simplicity but his designs were based on what he believed to be the appearance of late mediaeval ecclesiastical robes.

The Guild presumably survived so long because of these roots in service to the Roman Catholic Church. But perhaps it is significant that of the two founder mem- bers — men of some eccentricity and pas- sion — Gill left in 1924 and Pepler was expelled in 1933 for employing a non- Catholic at the Press. A level of harsh con- formity must have kept the show on the road. There were few post-war recruits and most of them were relations or near rela- tions. Edgar Holloway, wood-engraver and letterer, arrived in 1949, KilBride's daugh- ter Jenny, a weaver like her father, became the first woman member in 1974 and in 1983 KilBride's grandson Ewan Clayton, a gifted calligrapher, was admitted.

Clearly the Guild was at its strongest during the inter-war period. Enterprises like Ditchling and the activities of the craft movement in general are often dismissed as mere footnotes to art and design history. But the plain purity of printing at Pepler's Press, the lettering of Gill and Johnston and Ethel Mairet's simple weaves and nat- ural dyes were all attempts to get back to basics, to take a discipline and investigate its roots. When we think of modernism we tend to be narrow-minded. We think of design for mass production, of artistic movements like De Stijl, Futurism and Cubism. The work of Gill, Johnston and Mairet make it clear that the craft move- ment of the period, with its commitment to simplicity and to restructuring society, was just as radical.

Previous page

Previous page