The Post-Raphaelites

Baroque Art and Architecture in Central Europe. By Eberhard Hempel. Pelican His- tory of Art. (Penguin Books, 5 gns.)

THE High Renaissance, according to Woelfflin, was a narrow ridge, crossed almost as soon as it was reached. But crossed into what? We owe much of the work done here and in the United States on this curiously absorbing question, in- cluding the research for Manchester's successful exhibition, `Between Renaissance and Baroque,' to • expatriate scholars. It may be their own ex- perience of violent disintegration in Europe that

has stimulated new inquiry into the traumatic effects of the sack of Clement VII's Rome. The result, at all events, has been an increasing sug- gestion of the appeal of Mannerism to our con- temporary sensibilities. Dr. Hauser, whose four- volume Social History of Art precludes any charge of myopic specialisation, now marshals his evidence of the positive and revolutionary aspects of a period that saw 'one of the deepest breaks in the history of art'—the rediscovery of which 'implies a similar break in our own day.'

There is still, of course, a name to struggle with. Gothic has ceased to Mean barbarous and Baroque has ceased to mean bizarre, but Man- nerism seems condemned to convey, at its least pejorative, a sense of limitation. Its recovery has been not so much a revaluation of minor or neglected artists (though that is naturally in- volved) as a breaking out from the con- striction of a word. Constriction and isolation exist, it is true, in the theme itself, pairing with movement and communication in one of Man- nerism's powerful dualities. What we break out of may be the small, windowless studiolo of Cosimo de Medici in the Palazzo Vecchio, col- lectively embellished by twenty-six artists with a secretive air which Dr. Hauser identifies as characteristic. Escaped from Italy, we may have to break out again, from the Inds clos of the Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, or from the fresh but still circumscribed atmosphere of Fon- tainebleau. What we break into became, in the Amsterdam exhibition of 1953, the 'Triumph of Mannerism,' the festival of a harvest wide enough to deserve Council of Europe patronage. Man- nerism, explains Dr. Hauser in a phrase that can be commended to the uncertain student, is the form in which the Renaissance became a general European movement.

Here, alas, one begins to feel almost as ex- cluded as if General de Gaulle had read the proofs. In a large and scholarly coverage Hans Eworth finds no mention, nor Hilliard, nor Oliver (admitted, after all, in Amsterdam). The English Renaissance remains a literary, not even an architectural spectacle. One hastens to add (but to leave to other critics) that Shakespeare and the metaphysical poets receive considerable attention in the large portion of his work which Dr. Hauser devotes to Mannerism in literature, not pausing till he reaches Proust and Kafka. But that is the peril of an expansive subject and a fascinating book. Of course, literature has its place, but why not music?

Even in painting, with Vasari's gran maniera as the almost forgotten point of impact, the ripples are still spreading, washing the knees of giants. Tintoretto, who in Dr. Hauser's earlier work was 'in essentials, remote from international mannerism,' rates twenty-eight re- productions in Marinerisin (El Greco gets twenty-one). Apart from minor objections (the National Gallery's 'key' Bronzino appears in its uncleaned state of years ago) this volume of plates is a handsome reference work in itself. For such abundance many will be ready to forgo the not always certain joys of colour: yet not quite without regret, since any rediscovery of Mannerism offers particular adventures in colour, often without the benefit of familiarity with the original.

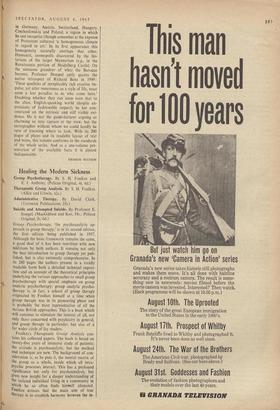

The Pelican History of Art, superbly picking its way over an immense terrain under the synoptic eye of Dr. Pevsner, reaches in its latest volume another landscape that has had to be rescued from depreciation. Professor Hempel, of Dresden, covers painting and sculp- ture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and mother-architecture from somewhat earlier, in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland, a region in which he can recognise (though somewhat at the expense of Protestant cultures) 'a homogeneous climate in regard to art.' •In its first appearance this homogeneity naturally overlaps that other, Humanist, cosmopolis discovered by the his- torians of the larger Mannerism (e.g., in the Renaissance portion of Heidelberg Castle). On the sensuous grandeur of what the Baroque became, Professor Hempel aptly quotes the native retrospect of Richard Benz in 1949: 'These qualities of inexplicably rich creative im- pulse; yet utter remoteness as a style of life, must seem a lost paradise to us who come later.' Doubting whether they can seem even that to the alien, English-speaking world (despite ex- pressions of fashionable respect), he has con- centrated on the intrinsic and still visible evi- dence. He is not • the guide-lecturer arguing or charming us into rapture at the view, but the cartographer without whom we could hardly be sure of knowing where to look. With its 200 pages of plates and its readable -layout of text and notes, this volume conforms to the standards of the whole series. And as a one-volume pre- sentation 'of the available facts it is almost indispensable.

FRANCIS WATSON

Previous page

Previous page