Exhibitions

The Romantic Spirit in German Art 1790 — 1990 (Royal Scottish Academy and the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, till 7 September) William Gillies Watercolours of Scotland (Scottish Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh till 25 September)

Visual treats

Giles Auty

Athis year's Edinburgh Festival gets under way, the present and future role of the visual arts as part of this annual event remains unclear and unfortunate. The important and historic role of the visual arts as an integral part of the programme

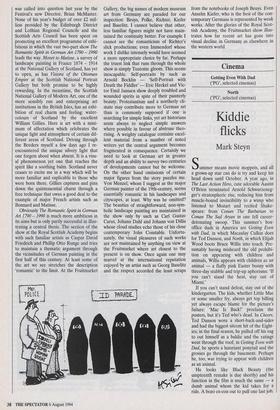

`Self-portrait in front of the easel, 1828, by Victor Emil Janssen was called into question last year by the Festival's new Director, Brian McMaster. None of his year's budget of over £2 mil- lion provided by the Edinburgh District and Lothian Regional Councils and the Scottish Arts Council has been spent on promoting an excellent programme of exhi- bitions in which the vast two-part show The Romantic Spirit in German Art 1790 - 1990 leads the way. Monet to Matisse, a survey of landscape painting in France 1874 - 1914 at the National Gallery of Scotland, has yet to open, as has Visions of the Ottoman Empire at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery but both promise to be highly rewarding. In the meantime, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, one of the more sensibly run and enterprising art institutions in the British Isles, has an exhi- bition of real charm and feeling: water- colours of Scotland by the excellent William Gillies. Here is art with a mini- mum of affectation which celebrates the unique light and atmosphere of certain dif- ferent areas of Scotland. Driving through the Borders myself a few days ago I re- encountered the unique silvery light that one forgets about when absent. It is a visu- al phenomenon yet one that reaches the spirit like a soothing balm. Scotland never ceases to excite me in a way which will be more familiar and explicable to those who were born there. Gillies captures and pins down the quintessential charm through a free technique that owes a good deal to the example of major French artists such as Bonnard and Matisse.

Obviously The Romantic Spirit in German Art 1790 - 1990 is much more ambitious in its aims but is only partly successful in illus- trating a central thesis. The section of the show at the Royal Scottish Academy begins with such familiar artists as Caspar David Friedrich and Phillip Otto Runge and tries to maintain a thematic argument through the vicissitudes of German painting in the first half of this century. At least some of the art we see stretches the description `romantic' to the limit. At the Fruitmarket Gallery, the big names of modern museum art from Germany are paraded for our inspection: Beuys, Polke, Richter, Kiefer and Baselitz. I cannot believe that other, less familiar figures might not have main- tained the continuity better. For example I cannot see the romanticism of Richter's slick productions; even Immendorf whose work I dislike intensely would have seemed a more appropriate choice by far. Perhaps the truest link that runs through the whole show is simply Teutonic gloom. This seems inescapable. Self-portraits by such as Arnold Bocklin — 'Self-Portrait with Death the Fiddler' — Eric Heckel and Vic- tor Emil Janssen show deeply troubled and wounded spirits in spite of their painterly beauty. Protestantism and a northerly cli- mate may contribute more to German art than is commonly supposed if one is searching for simple links, yet art historians seem always to neglect simple answers where possible in favour of abstruse theo- rising. A weighty catalogue contains excel- lent material from a number of noted writers yet the central argument becomes fragmented in consequence. Certainly we need to look at German art in greater depth and an ability to survey two centuries of developments cannot but be welcome. On the other hand omissions of certain major figures from the story puzzles me. Von Menzel, whom I suggest as the major German painter of the 19th-century, seems essentially romantic in his landscapes and cityscapes, at least. Why was he omitted? The beauties of straightforward, non-sym- bolic landscape painting are maintained in the show only by such as Carl Gustav Carus, Johann Dahl and Johann von Dillis whose cloud studies echo those of his close contemporary John Constable. Unfortu- nately, the visual pleasures of such works are not maintained by anything on view at the Fruitmarket where art closest to the present is on show. Once again one may marvel at the international reputation enjoyed by an artist such as Georg Baselitz and the respect accorded the least scraps from the notebooks of Joseph Beuys. Even Anselm Kiefer, who is the best of the con- temporary Germans is represented by weak works. After the glories of the Royal Scot- tish Academy, the Fruitmarket show illus- trates how far recent art has gone into visual decline in Germany as elsewhere in the western world.

Previous page

Previous page