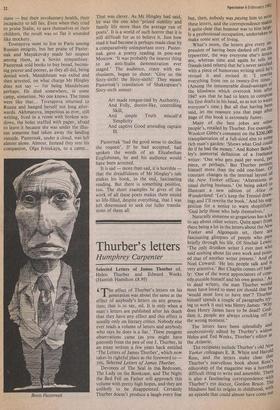

Thurber's letters

Humphrey Carpenter

Selected Letters of James Thurber ed. Helen Thurber and Edward Weeks (Hamish Hamilton £8.95) 6 The effect of Thurber's letters on his 1 generation was about the same as the effect of anybody's letters on any genera- tion; that is to say, nil. It is only when a man's letters are published after his death that they have any effect and this effect is usually only on literary critics. Nobody else ever reads a volume of letters and anybody who says he does is a liar.' These pungent observations came (as you might have guessed) from the pen of one J. Thurber, in an essay written a few years back entitled `The Letters of James Thurber', which now takes its rightful place as the foreword to yes, Selected Letters of James Thurber.

Devotees of The Seal in the Bedroom, The Lady on the Bookcase, and The Night the Bed Fell on Father will approach this volume with pretty high hopes, and they are unlikely to be disappointed. Certainly Thurber doesn't produce a laugh every line

but, then, nobody was paying him to write these letters, and the correspondence makes it quite clear that humour was to him large' ly a professional occupation, undertaken to make some sort of living. What's more, the letters give every jot' pression of having been dashed off on the typewriter, the way everyone else's letters are, whereas time and again he tells his friends (and others) that he's never satisfied, with a piece of humorous writing until he s revised it and revised it: 'I rewrite, everything from ten to twenty-five times% (Among the innumerable disadvantages of the blindness which overtook him after 1947 was that he had to learn to compose his first drafts in his head, so as not to waste everyone's time.) But all that having been said, let me reassure you that page after page of this book is extremely funny. Many of the best jokes are other people's, retailed by Thurber. For example, Woolcot Gibbs's comment on the $200,00° transplantation of a full-sized elm to some rich man's garden: 'Shows what God could do if he had the money.' And Robert Bench' ley's immortal definition of a freelance writer: 'One who gets paid per word, Per piece, or perhaps.' But Thurber permits himself more than the odd one-liner. Of constant changes in the internal layout of the New Yorker offices: 'Alterations as usual during business.' On being asked to illustrate a new edition of Alice in Wonderland: 'Let's keep the Tenniel draw- ings and 1'11 rewrite the book.' And his sug- gestion for a notice to warn shoplifters: `God help those who help themselves.' Naturally someone so gregarious has g lot to say about other writers. Quite apart from there being a lot in the letters about the New Yorker and Algonquin set, there are fascinating glimpses of people who pass briefly through his life. Of Sinclair Lewis: `The only drunken writer I ever met who said nothing about his own work and prais- ed that of another writer present.' And of Noel Coward: 'He lets people talk and is very attentive.' But Chaplin comes off bad- ly: 'One of the worst appreciators of com- edy outside himself and his own genius.' As to dead writers, the man Thurber would most have loved to meet (or should that be `would most love to have met'? Thurber himself spends a couple of paragraphs try- ing to work it out) was Henry James: 'Why does Henry James have to be dead? God- dam it, people are always crocking off at the wrong moment.' The letters have been splendidly and unobtrusively edited by Thurber's widow Helen and Ted Weeks, Thurber's editor at the Atlantic.

The recipients include Thurber's old New Yorker colleagues E. B. White and Harold Ross, and the letters make clear that

Thurber's marvellous book about Ross s editorship of the magazine was a horribly difficult thing to write and assemble. There

is also a fascinating correspondence with Thurber's eye doctor, Gordon Bruce. The blindness had its origins in childhood, with an episode that could almost have come out

Previous page

Previous page