NOT ENOUGH BANG FOR OUR BUCKS

David Hart argues that the

British fighting services are not giving value for money

BRITAIN'S armed forces have been active in more theatres during the first weeks of this year than they were in most of the Cold War. The Cheshires are in Bosnia. The Ark Royal and its escorts are in the Adriatic. RAF Tornados have attacked targets in Iraq twice in the last three weeks. The killing in Northern Ireland grinds on. Despite all the commitments, the defence budget, already stretched to breaking point, is to be cut by over 10 per cent in real terms over the next three years. Last week, in a speech to the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the For- eign Secretary categorically said that because of the restrictions imposed on the armed services Britain would have to accept a more limited role in the world police force. As a result, Mr Rifldnd, the Defence Secretary, faces problems graver even than those his recent predecessors faced and funked.

The defence establishment is like a nationalised industry. It is a monopoly sup- plier. Unlike any other nationalised indus- try, it has only one customer. Its effective- ness cannot be tested except in anger. And, because some of what it does needs to be secret, it is easy to keep those things that do not need to be secret from the public gaze. For all these reasons it is very hard for ministers or taxpayers to know how capable our armed forces are and whether we are getting value for money.

One way to get a grip on the perfor- mance of the MoD is to compare our bud- get and fighting capacity with those of other countries. Of course, every country has distinct national interests and so a dif- ferent defence strategy. Britain has a more significant nuclear deterrent than any other country, except America and Russia. But, in fact, Trident is a rare example of excellent value for money. Apart from providing us with a viable deterrent, it more or less ensures our seat on the UN security council.

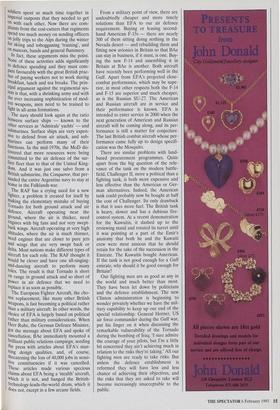

The chart below compares our fighting capacity with that of France and Israel, who are also nuclear powers. The compar- ison is illuminating. Our budget ($41.2 bil- lion) is almost 20 per cent larger than France's ($34.9 billion) and 7 times larger than Israel's ($6.7 billion). Despite that, both France and Israel have more combat aircraft, main battle tanks, armoured fight- ing vehicles and artillery pieces than we do. And France has a similar number of naval units and armed helicopters.

It is clear from the chart that France and Israel both seem to get more fighting capacity for their money than we do. Why do we not perform as well? There are two principal reasons. Our politicians will interfere; and over and over again the sys- tem that has been created by the defence establishment to procure for and adminis- ter our armed forces has protected itself from budgetary pressures by sacrificing fighting capacity.

Half of the defence budget is absorbed by salaries. We have a quite extraordinary number of senior officers compared with other nations. The ratio of British general officers (including nursing staff) to total servicemen is 1:420. In the United States and in France it is 1:1,900. In Germany it is 1:2,300. The British navy has as many admirals as ships. The RAF has an exces- sively top-heavy command structure with too many command groups controlling too few front-line squadrons. The army would undoubtedly accept quite a few more men and be prepared to command them with the same number of senior officers.

The failure of successive governments to reform the defence establishment has led to many other problems, including a long series of misguided decisions. The £1 bil- lion Nimrod fiasco was one of the more spectacular errors. As the pressure has increased so decision-making has, as you would expect, become increasingly secret. The latest series of decisions, which result- ed in 'Options for Change', were made in such secrecy that only half a dozen top offi- cials and officers were involved. Some consequences of the failures of decision-making were manifest during the Gulf war. In order for the army to deploy one division in the Gulf, four divisions were depleted to the point of ineffective- ness, three in Germany and one in Britain. The performance of the Challenger I tank was not good. The RAF felt unable to deploy Tornado F3 fighters because of the superior capabilities of Saddam's Mig-25s and -29s.

Other consequences are becoming clear today. The British army has no modern battlefield helicopters. In the hands of US forces, the Apache graphically demonstrat- ed its worth on the road to Basra. They would be very useful in Bosnia to cover an opposed retreat, if it became necessary. There is a dangerous overstretch or human resources. Our professional soldiers are supposed to have 24-month breaks between deployments away from their fam- ilies. With the demands of Northern Ire- land, Bosnia and other commitments for example, the Falklands, Belize and Cambo- dia — that period has now been reduced to 15 months and will fall further. It is no sur- prise that the Government has suggested that if the Kuwaitis want British troops to help defend them against Iraq, they can only have 200: a very token force.

The army also has a problem with doc- trine. Modern fighting involves high inte- gration of ground, air and naval forces into all-arms formations. This points to aboli- tion of the regimental system that grew out of the need to build on local territorial loy- alty and to serve a colonial power whose

Comparative Fighting Capacity (all figures from Military Balance 1992/93) Budget ($bn) All combat aircraft Fleet units Main battle tanks Armed helicopters* Armoured fighting vehicles Artillery pieces+ UK 41.2 511 161 1318 291 6083

762

France 34.9 910 148 1343 720

6268 1436

Israel 6.76 662 64 3890 93

8480 1420

*weapons-capable helicopters of all services +tube artillery only

soldiers spent so much time together in imperial outposts that they needed to get On with each other. Now there are com- plaints from the cost-cutters that regiments spend too much money on sending officers on Jolly trips to the Alps during the winter for skiing and tobogganing 'training', and cin mascots, bands and general flummery. In fact, these arguments miss the point. None of these activities adds significantly to defence spending and they must com- pare favourably with the great British prac- tice of paying workers not to work during breakfast, lunch and tea breaks. The prin-

cipal argument against the regimental sys- tem is that, with a shrinking army and with the ever increasing sophistication of mod- ern weapons, men need to be trained to fight in all-arms formations.

The navy should look again at the ratio between surface ships — known to the

other services as 'Admirals' yachts' — and

submarines. Surface ships are very expen- sive to defend from air attack, and sub-

marines can perform many of their functions. In the mid-1970s, the MoD dis- covered that more resources were being

committed to the air defence of the sur- face fleet than to that of the United King- dom. And it was just one salvo from a British submarine, the Conqueror, that per- suaded the entire Argentine navy to stay at home in the Falklands war.

The RAF has a crying need for a new fighter, a problem it created for itself by Making the elementary mistake of buying Tornado for both ground attack and air defence. Aircraft operating near the ground, where the air is thicker, need

,engines with big fans and not very swept- back wings. Aircraft operating at very high

altitudes, where the air is much thinner, need engines that are closer to pure jets and wings that are very swept back or delta. Most nations make different types of aircraft for each role. The RAF thought it would be clever and have one all-singing- and-dancing aircraft to perform many roles. The result is that Tornado is short On range in ground attack and so short of Power in air defence that we need to replace it as soon as possible.

The European Fighter Aircraft, the cho- sen replacement, like many other British weapons, is fast becoming a political rather than a military aircraft. In other words, the choice of EFA is largely based on political rather than military considerations. When Herr Ruhe, the German Defence Minister, got the message about EFA and spoke of cancellation, BAe immediately mounted a brilliant public relations campaign, seeding the press with articles about EFA's stun- ning design qualities, and, of course, threatening the loss of 40,000 jobs in sensi- tive constituencies if it was cancelled.

These articles made various specious claims about EFA being a 'stealth' aircraft, which it is not, and banged the British- technology-leads-the-world drum, which it does not, except in a few arcane fields. From a military point of view, there are undoubtedly cheaper and more timely solutions than EFA to our air defence requirement. Buying or leasing second- hand American F-15s — there are nearly 300 of them sitting doing nothing in the Nevada desert — and rebuilding them and fitting new avionics in Britain so that BAe can stay in business, if it must, is one. Buy- ing the new F-14 and assembling it in Britain at BAe is another. Both aircraft have recently been performing well in the Gulf. Apart from EFA's projected close- combat performance, which may be supe- rior, in most other respects both the F-14 and F-15 are superior and much cheaper, as is the Russian SU-27. The American and Russian aircraft are in service and their performance is known. EFA is intended to enter service in 2000 when the next generation of American and Russian aircraft will be coming along, and its per- formance is still a matter for conjecture. The last British combat aircraft whose per- formance came fully up to design specifi- cation was the Mosquito.

There are similar problems with land- based procurement programmes. Quite apart from the big question of the rele- vance of the tank on the modern battle- field, Challenger II, more a political than a fighting tank, is both more expensive and less effective than the American or Ger- man alternatives. Indeed, the American tank could probably now be bought at half the cost of Challenger. Its only drawback is that it uses more fuel. The British tank is heavy, slower and has a dubious fire- control system. At a recent demonstration for the Kuwaitis, it dashed up to the reviewing stand and rotated its turret until it was pointing at a part of the Emir's anatomy that both he and the Kuwaiti crew were most anxious that he should retain for the sake of the succession in the Emirate. The Kuwaitis bought American. If the tank is not good enough for a Gulf emirate, why should it be good enough for Britain?

Our fighting men are as good as any in the world and much better than most. They have been let down by politicians and the defence establishment. The new Clinton administration is beginning to wonder privately whether we have the mil- itary capability to keep up our end of the special relationship. General Horner, US air force commander during the Gulf war, put his finger on it when discussing the remarkable vulnerability of the Tornado during the bombing of Iraq. 'I sure admire the courage of your pilots, but I'm a little bit concerned they ain't achieving much in relation to the risks they're taking.' All our fighting men are ready to take risks. But unless the defence establishment is reformed they will have less and less chance of achieving their objectives, and the risks that they are asked to take will become increasingly unacceptable to the public.

Previous page

Previous page