The Jesuits as heroes

Euan Cameron

LAND WITHOUT EVIL by Richard Gott Verso, £18.95, pp. 320 THE CAPTAIN'S WIFE edited by Elizabeth Mayor Weidenfeld, f18.99, pp. 187

I . n the book trade of the late Sixties, pub-

lishers were fond of quoting Jonathan Cape's remark to the effect that a wise man Would always publish a book about Nelson, but should never contemplate a book about South America. Since then, fortunately, certain Latin American novelists, the Brazilian rainforests, at least two military dictatorships and the Falklands war have done their bit to challenge the sense of that dictum, and these two books are further evidence of a change of focus. It was in the Sixties, too, that the guerril- la leader Ernesto `Che' Guevara was cap- tured and shot by Bolivian government forces. At that time anyone moved by the high idealism and daring of Guevara's exploits felt grateful to Richard Gott who, by virtue of his brilliant reporting in the Guardian, was one of the very few British Journalists who appeared to care about events in those distant lands. Gott's experience of the Bolivian swamp- lands first fired his interest in the history of these regions and the Indian nations that once populated them, and several return Journeys and many months of research have resulted in this handsome and unusual book. It takes the form of a jour- Ilk Mato from Campo Grande in the Brazilian ,..1nato Grosso westwards over the vast rioodplains of the River Paraguay, known as the Pantanal, to the north-eastern Bolivian province of Mojos. But it is not Gott's personal journey that matters in this book; it is the accounts of earlier travellers over the 400 years since Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores

brought Christianity and European civilisa- tion to the Indian tribes: priests and mis- sionaries, soldiers, explorers and settlers who forged their way through the inhospitable watershed in search of El Dorado, new land for empire, new peoples for Christ.

Richard Gott's achievement is to have brought these travellers' accounts together and to have blended them into a cohesive historical summary that enables us to glimpse what the extermination of the South American Indians may mean. Between 1650 and 1700 the Spanish led no less than 50 expeditions against the Guaycuru Indians alone. Gott quotes authoritative sources that conclude that the pre-Conquest population of the Americas was closer to 100 million rather than the ten million thought hitherto.

Exhaustive research has unearthed a colourful array of intrepid travellers who preceded Gott. Men like the sonorously- named Alvar Ntifiez Cabeza de Vaca, a Spaniard who in 1543, hacking his way through jungle and swamp in search of a passage from the Atlantic to the Inca trea- sures of Peru, happened to discover the Falls of Iguazii. He must have thought he had come across the Garden of Eden. A stream of Europeans, all leaving detailed accounts, followed in the 19th century: the English explorer, Colonel Fawcett; the Swede, Baron NordenskjOld; the French noblemen, Alcides Dessalines d'Orbigny and the Count of Castelnau; Luigi Balzan, an Italian naturalist; the German engineer, Franz Keller, and many others.

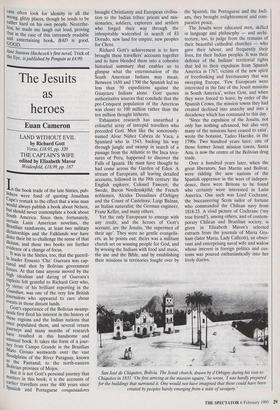

Yet the only Europeans to emerge with any credit, and the heroes of Gott's account, are the Jesuits, 'the supermen of their age'. They were no gentle evangelis- ers, as he points out; theirs was a militant church set on winning people for God, and by wooing the Indians with food and music, the axe and the Bible, and by establishing their missions in territories fought over by the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Indi- ans, they brought enlightenment and com- parative peace. The Jesuits were educated men, skilled in language and philosophy — and archi- tecture, too, to judge from the remains of their beautiful cathedral churches — who gave their labour, and frequently their lives, for their Indian peoples. It was their defence of the Indians' territorial rights that led to their expulsion from Spanish America in 1767, victims of the new spirit of freethinking and freemasonry that was sweeping Europe. 'Few Europeans were interested in the fate of the Jesuit missions in South America', writes Gott, and when they were forced to leave, by order of the Spanish Crown, the mission towns they had created declined into anarchy and into a decadence which has continued to this day.

`Since the expulsion of the Jesuits, not only has nothing advanced, but also very many of the missions have ceased to exist', wrote the botanist, Tadeo Haenke, in the 1790s. Two hundred years later, one of those former Jesuit mission towns, Santa Ma, is now the centre of the Bolivian drug trade.

Over a hundred years later, when the great liberators, San Martin and Bolivar, were ridding the new nations of the Spanish oppressor in the wars of indepen- dence, there were Britons to be found who certainly were interested in Latin America. One such was Lord Cochrane, the buccaneering Scots sailor of fortune who commanded the Chilean navy from 1818-23. A vivid picture of Cochrane Cm true friend'), among others, and of contem- porary Chilean and Brazilian society, is given in Elizabeth Mayor's selected extracts from the journals of Maria Gra- ham (later Maria, Lady Callcott), an obser- vant and enterprising naval wife and widow whose interest in foreign politics and cus- toms was poured enthusiastically into her lively diaries.

San Jose de Chiquitos, Bolivia. The Jesuit church, drawn by d'Orbigny during his visit to Chiquitos in 1831. 'On first arriving at the mission square,' he wrote, 'I was hardly prepared for the buildings that surround it. One would not have imagined that these could have been created by peoples barely emerging from a state of savagery.'

Previous page

Previous page