The Northcliffe of the Nile

By WILLIAM HARCOURT IT is very difficult to buy a round of drinks for an Arab, and Sayed Mekkawi was standing me a cup of whisky on the red-tiled terrace of the Cultural Centre, formerly the Junior British Officials' Club, Khartoum.

'You are unemployed at the moment, Your Excellency?' Mekkawi asked.

'I am, Sheikh of Sheikhs,' I replied. The use of these fancy titles is one of those double-take jokes which show that both parties are free from imperialism and anti-imperialistic prejudice.

`Oh,' said Mekkawi. 'Tell me, can you spell?'

'English?'

'Naturally.'

'As well as the next man,' I said. 'Why?'

Mekkawi slid a massive brown paw into the pocket of his white nightshirt-like gellibya and brought out a limp letter.

'Honour me by reading this,' he said.

As I read, he signalled for two more cups of whisky. The letter was from the Ministry of the Interior, informing Mekkawi that unless the standard of the English edition of the Khartoum Times improved forthwith, his licence to publish would be withdrawn.

'Standard?' I echoed from the letter.

'The spelling,' Mekkawi explained. He waved his hand wearily over his damp face; it was a matter he was loath to dwell on.

'As you know, we do not distinguish your English "p" and "b" in Arabic.' He dipped into his pocket again and brought out a crumpled copy of his paper.

The banner headline read, 'WELCOME TO BANDIT NEHRU.

'There have been other unfortunate typo- graphical errors,' said Mekkawi in his cultured Oxford accent. 'Last week we had Khrushchev's "massage" and a "litter" from your Mr. Mac- millan. There have been complaints. The Minister doesn't appear to believe there is room for honest error. Or 'perhaps,' he sighed resignedly, 'he doesn't want to believe it.'

We sat in silence for a moment. Mekkawi seemed half asleep, sprawled in a deckchair, almost buried beneath his own belly. Then he roused himself. `Do me the honour of taking employment in my establishment,' he said. 'Forty Egyptian pounds per month for three hours' work each evening, except Fridays, and all the latest scandal thrown in buckshee.'

As jobs don't grow on date palms around Khartoum I agreed—and then, feeling the need to make some generous gesture, I said medita- tively. 'One changes with the times.'

Mekkawi closed his eyes again. He knew what was coming.

'New Establishments are sensitive,' I said.

'The Old Civil Secretary seemed to rather enjoy Your exposures of the more intimate side of his life but now things are different. Perhaps the Minister's attitude might change if you stopped hinting about his relatives being mixed up in the Vice trade in Egypt. Perhaps you should let it be known that you've destroyed those photostats of Egyptian police records you have in that safe in your office' Mekkawi sat bolt upright and made a sweeping gesture with his arm. 'It's all gone,' • he said. 'Swept away. Colonialism and all its spawn has disappeared. No more corruption, no more .nepotisin, no more degeneration.' He made a rude Arab sound with his lips and called for two more cups of whisky.

The next evening, as the sun dropped into the Nile, I walked to the Times offices for the first time; through Khartoum's old brothel quarter— down dusty unpaved streets and narrow, furtive, mud-walled alleyways. As I passed, the Ethiopian and Arab girls, in European and Arab dress squatting in their doorways, discreetly dropped their veils and whispered, 'tali herta' ('come here'). Further on Ethiopian girls, clad only in semi-transparent cotton frocks, blatantly rolled their bellies and screamed enticements in Arabic. I heard one old-fashioned call in English, 1 am a virgin, Tommee.' Each street-corner café was a masculine oasis of yellow light and blaring Arab music.

Mekkawi's offices were in a broken-down red brick house squeezed in between a brothel and a street-corner café. He greeted me at the door and showed me over the building. In the front room stood his 'foreign correspondent,' a radio from which he filched the BBC news. In the former harem part of the house stood the press, not too firmly attached to a concrete base. Stamped on it was 'Hamburg 1898,' the year of Kitchener's re-conquest of Khartoum.

As we watched at the door the operator switched the press on and bolted past us like a powder-monkey. The whole house started to vibrate as it groaned and clashed into move- ment like a steam-engine on slippery rails. No one was allowed in the room while the press was in motion, Mekkawi explained. When the pres- sure was too great, blocks were liable to fly out and embed themselves in the walls.

The compositors were working on the back verandah, ankle-deep in a mess of discarded paper and printer's ink. Here I met other mem- bers of the staff: the foreman, a brown Buddha of a man on the run from Gamal Abdel Nasser; and a mournful, seven-foot-tall Christian Dinka from the Southern Sudan who could read and write English quite fluently, when sober.

On the third night Of my new job I was work- irig away, more ór less happily, when Nafissa, the madame from next door, stuck her head over the wall. Things were slack, she explained, and perhaps we might like to pop over for a bit of relaxation. Mekkawi was out filling up with whisky and gossip at the Grand Hotel, so the staff downed tools to a man and invited me to follow them over the wall.

The sitting-room of Nafissa's house was dom- inated by a large portrait of Queen Victoria. Nafissa herself was a walking treasure chest of gold bracelets stretching from her wrists to her elbows, and necklaces of Maria Theresa gold sovereigns stretching from her waist to her neck. The Arabs called her 'arrousat el Nil' ('the beauty of the Nile'). Her fat cheeks were marked with wide vertical cicatrices and her massive bulk was always wrapped in yards of spotless white muslin. Sometimes she would allow her veil to slip from her head exposing her hair, set in hundreds of straight, tiny plaits, greased with animal fat.

We passed the time gossiping with Nafissa's favourite girls and supping on hatnaam, young pigeons lightly grilled on a charcoal fire, washed down with aragi, a fiery liquor distilled from dates, with a kick like a racing camel.

About 11 p.m. Mekkawi burst in full of whisky and abused us, invoking the aid of the Prophet against us for wasting office time in a brothel. I learnt later this happened at least once a week.

I got on well enough with Mekkawi until the dry season, when tempers rose with the tempera- ture. Some days it was 120 in the shade and Khartoum was like the stoke-hole of a coal- burning tramp steamer. News was slack, circula- tion was falling, and as there is no circulation- booster like British imperialism, Mekkawi started on a series of editorials.

We had a difference of opinion, for example, over the editorial on malaria which started, 'We have many insects in the Sudan due to fifty years of British Imperialism.' Quite logical, Mekkawi argued; the British had been in control for fifty years and they should have done something about the mosquitoes.

I also remember ineffectually objecting to his 'cocoa colonialism' campaign. Pepsi-Cola was already well established in the Sudan while Coca-Cola was just moving in. Mekkawi ap- proached the Coca-Cola company with a proposi- tion. He would produce a Coca-Cola supplement along with an editorial implying that the essence of Pepsi-Cola was made from 'pepsin' which is made from the intestines of pigs. The com- pany refused, so Mekkawi launched his campaign against 'cocoa colonialism.'

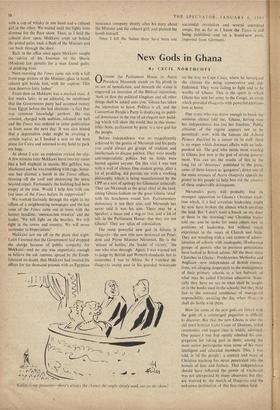

Now while there is no harm, and perhaps some advantage, in whipping the tired old lion in the Middle East, the new Establishments are a different matter and Mekkawi could not let sleep- ing dogs lie. One night, about six months after I had siarted on the Times, Mekkawi burst into the office, grabbed the I.eica and beckoned me to follow him. His old enemy, the Minister, was whooping it up in the Kitchener Cabaret. Sure enotigh, when we entered the,cabaret, we saw the Minister sitting at a table behind a potted palm with a cup of whisky in one hand and a cabaret girl in the other. We waited until the lights were dimmed for the floor show. Then, as I held the cabaret door open, Mekkawi crept up behind the potted palm, took a flash of the Minister and ran back through the door.

Back in the office once again Mekkawi sought the advice of his foreman on the Sharia (Moslem) law penalty for a man found guilty of drinking wine.

Next morning the Times came out with a full front-page picture of the Minister, glass in hand, cabaret girl beside him, with the caption 'This man deserves forty lashes.'

From then on Mekkawi was a marked man. A few weeks later, in an editorial, he mentioned that the Government party had accepted money from Egypt before the last elections—a fact that was common knowledge anyhow. He was arrested, charged with sedition, released on bail and the Times was ordered to cease publication as from noon the next day. It was also hinted that a deportation order might be awaiting a certain inglesi, so I booked a seat on the next plane for Cairo and returned to my hotel to pack my bags.

At about 2 a.m. an explosion rocked the city. A few minutes later Mekkawi burst into my room Like a bull elephant in season. His gellibya was blackened and he was trembling with rage. Some- one had planted a bomb in the Times offices, blowing off the roof and destroying the press beyond repair. Fortunately the building had been empty at the time. Would I help him with one last issue of the Times before its suppression?

We worked furiously through the night in the offices of a neighbouring newspaper and the last issue of the Times came out at noon with the banner headline, 'IMPERIALISM STRIKES' and the leader, 'We will fight on the beaches. We will fight in the towns and country. We will never surrender to Imperialism.'

Mekkawi saw me off on the plane that night. Later I learned that the Government had dropped the charge because of public sympathy for Mekkawi—and no one was unpatriotic enough to believe the suk rumour, spread by the Estab- lishment no doubt, that Mekkawi had insured his offices for ten thousand pounds with an Egyptian insurance company shortly after his story about the Minister and the cabaret girl; and planted the bonib himself.

Since I left the Sudan there have been one successful revolution and several attempted coups, but as far as I know the Times is still being published—and on a brand-new pres. imported from Germany.

Previous page

Previous page