Arts

Poor man's Titian?

Bruno Wollheim

Modest, down-to-earth, a shade dry but with a determined, even stubborn, eye, and jaw: the qualities of the first portrait we see on entering the small Moroni exhibition in the National Gallery, mounted to commemorate the 400th anniversary of his death, make it a likely candidate to be a self-portrait of the artist nicknamed the poor man's Titian and whose unassuming talents led to his comparative neglect. But while we would not find it hard to think we could be fooled as Van Dyck was, when, on his Italian journeys, he copied a Moroni in his sketchbook under the mistaken assumption that it was by his far greater and more famous contemporary, we can still appreciate those qualities of a portraitist which made him a particular favourite among English collectors. The strength of British collections has meant we have been given a rich and representative selection of Moroni's portraits (including for good measure a religious and allegorical subject), and their special cleaning for the show has restored their original clear, early-morning brilliance.

The putative self-portrait takes on a special significance, for two reasons. We know almost nothing about Moroni himself and unlike the pointed and neurotic portraits of Lotto or the Shakespearian pathos and universality of Titian's, Moroni's are curiously self-effacing and neutral. His sitters, whether nervous newly-weds, disdainful nobles, proud warriors or simple tailors, look out at us as if denying the artist's mediation. Rare in this the most artificial and self-conscious era of painting; Moroni takes as his point of departure the modest aim of descriptive truth and in this way recalls the ambitions of earlier fifteenthcentury artists. But exactly this refusal, or inability, to extract univeral truths of man's condition, to explore particular states of mind, or as Bronzino did, to make a face, the jewelled mirror to a world of manners, allows us to inspect under a magnifying glass the society of Bergamo where Moroni spent most of his life.

Trained under Moretto in Brescia, Moroni returned to Bergamo, a town under Venetian rule at the foothills of the the Alps near his birthplace, sometime after his master's death in 1554. There he lived until his death in 1578 where he was the most respected artist. The earliest portrait in the exhibition of a seated lady probably done while still in Brescia, shows an already developed fascination with Venetian colour and optical effects in the description of the heavy satin and a more local Lombard concern for exact still-life effects in the treatment of details and in the ordering of the composition.

But Moroni's ability exactly to describe his sitters and to project a breathing likeness onto canvas goes beyond any previous Italian example. The tentative diligence with which he traces the contours and volumes of objects in this early portrait, particularly evident if one looks at the chair and its uneasy relation to the floor and the sitter, suggests an artist to whom nothing comes easily and whose gifts lay less in the imagination than in the realisation and probing of the tangible. Whether in this tender study of a meek, hyper-sensitive girl, in the forbidding, suspicious, even malicious scrutiny of the portrait of the formidable Pace Spini with her mole, or in the haughty arrogance of the thoroughbred Count Lupi, Moroni's vision is steadfastly fixed on the surface of things. Sometimes the forms have a papery insubstantiality in spite of their proclaimed volume. His subtle characterisations are more descriptive than psychologically penetrating, making us search for their inner meaning as we might regard strangers on a train. This literalism is both his strength and weakness. The ferocious ineptitude of his earthbound 'Allegory of Chastity' and his unconvincing 'Marriage of St Catherine' embarrassingly display his shortage of imagination.

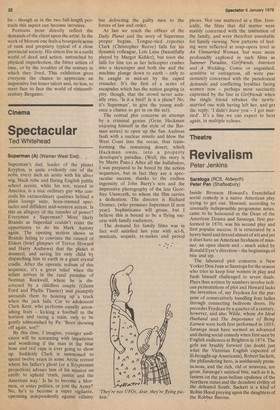

The central focus of the show, and its undoubted masterpiece, is the 'Portrait of a Tailor.' Caught within a stilled, fine-woven fabric of muted greys and silver tones, the only warm accent the deep claret of his doublet, he stands against a plain background and stares out at us with a calm dignity as he prepares to cut the cloth before him. It is an extraordinary image of directness and simplicity. Except for the engagement of the gaze, for a certain studied quality to the pose and the design and for a dwelling of on the face, this portrait, coming closer to prose than any other sixteenthcentury work before the Carracci, looks forward to Degas's life-studies as the excellent catalogue to this exhibition mentions. The exaltation of the craftsman and the almost spiritual meditation on his tools of trade goes beyond the painting's crude ' advertising function and vindicates the painter's limitations. It is as if the act of painting itself, bound up with difficulty and the obession with the material and the detail, has found its sympathetic equivalent for Moroni in the subject of a fellow craftsman. This down-to-earth celebration of the inhabited world is a feature of all of Moroni's best paintings and is especially present in the posthumous 'Portrait of a Scholar' from Edinburgh and the intimate group-portrait of 'The Widower' from Dub tin — though as in the two full-length portraits this aspect can become intrusive.

Portraits most directly reflect the demands of the client upon the artist. In the work of Moroni one feels a bourgeois sense of rank and propriety typical of a close provincial society. His sitters live in a sunlit world of deed and action, untouched by physical imperfection, the bitter action of time, or by the troubles of the century in which they lived. This exhibition gives everyone the chance to appreciate an impressive but lesser talent and, no less, to meet face to face the world of sixteenthcentury Bergamo.

Previous page

Previous page