Notebook

The events of recent days in Iran now point, in a depressingly inevitable way, to a long period of instability which is likely to persist whether or not the Shah remains as the head of government. The prospective new prime minister Dr Shapour Bakhtiar — a member of the powerful Bakhtiari tribe which has a history of opposition to the monarchy — has been out of touch with his country, having spent several years in Germany since the fall of Mossadeq in 1953. However, he will have more chance of restoring some order if, as rumoured this week he has the tacit support, for six months, of Ayatollah Khomeini. If, the Shah does leave Iran for a 'vacation' it should not necessarily be interpreted as a. flight into exile. When the Shah left, the country in 1953 there was a wellorganised rising in his favour and he returned to Iran after six days. The man who advised him to leave, and replaced Mossadeq as prime minister, was General Zahedi, whose son, Ardeshir Zahedi, is now at the Shah's side. However, the situation is very different to-day and Dr Bakhtiar has said that he expects the Shah to leave Teheran for eighteen months, and to return only as a constitutional monarch. The Shah has achieved much for Iran — particularly in the fields of education and social welfare — but latterly he has acted outside the Constitution of 1906, at the peril of his country's future. Only two years after the Constitution was drawn up another Shah, Mohamed Ali, attempted to suspend it. The result was civil war: the Bakhtiaris used their influence against the Shah, and he was deposed, to be succeeded by his young son, Ahmed, a completely ineffectual ruler who was the last of the Qajar dynasty.

I was sorry to hear that Mr Justice Melford :Stevenson will be retiring from the Bench at Easter. If the sentences which he handed down seldom erred on the side of leniency, he was generally regarded as a fair judge (although the Court of Appeal once, in 1976, reversed three of his hudgments in a day). But his manner in court — well described by the name of his Sussex house, 'Truncheons' — did not always endear him to the barristers who appeared before him. Several years ago at the Old Bailey Mr Michael Beckman, having been addressed repeatedly by Melford Stevenson, in a less than friendly tone, as 'Mr Beckstein', was moved finally to inform the judge that he was in no way connected with the manufacturers of grand pianos. However, his impatience with counsel was often used to good effect, cutting through a lot of the unnecessary argument in which too many barristers today are prone to indulge. Melford Stevenson was appointed a High Court judge in 1957, three years before the regulation was made requiring all judges to retire at seventy-five. One of the few others who remain outside that rule is the Master of the Rolls, the great Lord Denning, who will surely continue on the Bench long after his eightieth birthday this month.

Proceedings for the extradition of Astrid Proll, the Baader-Meinhof suspect, are at last due to begin at Bow Street on Monday, almost four months after she was arrested in London. She has remained in Brixton prison since the middle of September. No sufficient explanation has been given by the West German government for the in-. ordinate delay; the charge against her is attempted murder, the same one on which she was first tried in Frankfurt in 1973. (Miss Proll escaped from a hospital, and the trial was never completed.) But there is a further, and even more unsatisfactory, feature of this case. Miss Proll has claimed that, having married a British citizen in 1975, she is protected from extradition. The Home Office has refused to register her as a British national on the grounds that there is some doubt, as to the validity of her marriage. And the Court of Appeal decided, three weeks ago, that the Home Office was entitled to delay the registration. However, a few days after she had formally applied for British citizenship, an Order in Council was made giving the Home Secretary the discretion to extradite the spouses of British citizens. The Order was 'laid before' Parliament on 2 October (while the House was in recess) and brought into operation the following day. There may be compelling reasons why suspected foreign criminals should not be allowed to take advantage of our nationality laws. But it is quite wrong that a regulation of such consequence should be slipped through in this surreptitious way. As Tom Harper wrote recently in the New Law Journal: 'It gives one cause to wonder whether the exclusion of Parliament in this instance was not deliberately contrived.' What is required is a general review of the extradition laws, which have not been revised since an Act of 1870. This Act provides that there can be no extradition for an offence 'of a political character', an argument which Miss Proll is likely to put forward next week.

Some people are born sensitive to public criticism; some are big enough to let it ride over them. Among the first category is Sir Harold Wilson, our most litigious politician, who has issued more writs for libel than he had years as prime minister; while Lord Home, who used frequently to be held up to ridicule and contempt in the newspapers, has never resorted to legal or any other action in reply. The fact that Wilson is now discredited and Home generally respected is attributable in no small way to the response of each man to the critical comment directed against him. As a _further illustration of the point, the Spectator's 'high life' correspondent Taki, the arbiter of all that is elegant and fashionable, recently wrote, in a light-hearted article, that the Clermont (a gambling club in London owned by the Playboy organisation) was one of the places 'one should not be seen dead or alive in.' It might therefore be thought otiose formally to ban Taki from going there. But banned he was, in a letter written to him by a Krystyna Wosiek informing him that his membership of the club was cancelled and that 'you are unable to use the facilities of the Club either as a member or as a guest of a member.' Apparently the Clermont is not now enjoying the same popularity which it once used to.

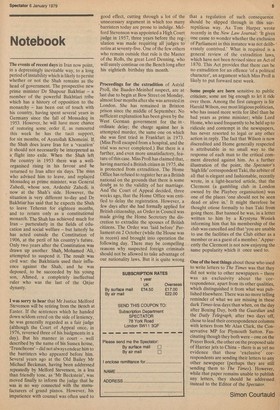

One of the best things about those who used to write letters to The Times was that they did not write to other newspapers — there was an exclusivity about the correspondence, apart from its other qualities, which distinguished it from what was published elsewhere. There was no more telling reminder of what we are missing in these dark Times-less days than when, on the day after Boxing Day, both the Guardian and the Daily Telegraph, after two days off, chose to lead their correspondence columns with letters from Mr Alan Clark, the Conservative MP for Plymouth Sutton. Fascinating though they both were —one on the Prayer Book, the other on the proposed sale of Harrier jets to China — there is as yet no evidence that those 'exclusive' correspondents are sending their letters to any other newspaper (perhaps they are still sending them to The Times). However, while that paper remains unable to publish any letters, they should he addressed instead to the Editor of the Spectator.

Simon Courtauld

Previous page

Previous page