Exhibitions

Enigmatic genius

David Anfam on the extraordinary rewards to be found in the show celebrating the work of the Dutch master, Johannes Vermeer At lovers face a tough choice this win- ter. They can either brave the wilderness of downtown Washington DC now or wait a few months and go, perhaps setting off by Eurostar, to the relatively urbane city of The Hague. No matter which they choose the rewards are extraordinary. Twenty-one of the approximately 35 paintings by the 17th-century Dutch master Johannes Ver- meer have been gathered together in an exhibition that is unlikely ever to be repeat- ed. At the Mauritshuis in The Hague the selection on display at the National Gallery of Art will be further strengthened by 'The Love Letter' and the magisterial 'Milk- maid' from Amsterdam.

To study the groups of Vermeers in New York's Metropolitan and the Frick or Washington's National Gallery itself offers a special experience, but having these and a significant number of others in one place involves not just a logistical triumph. It brings the viewer face to face with the sort of intensity that reminds us that, whatever `art' is, the simplest definition is to say that it provides something available nowhere else. And where else can one find the enig- matic, even disquieting serenity that is the essence of Vermeer?

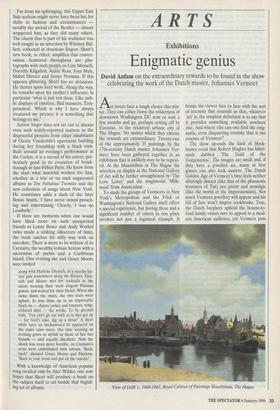

The show up-ends the kind of block- buster event that Robert Hughes has hilari- ously dubbed 'The Gold of the Gorgonzolas'. The images are small and, if they have a jewelled air, many at first glance can also look austere. The Dutch Golden Age of Vermeer's time feels neither alluringly distant (like that of the pharaonic treasures of Tut) nor pretty and nostalgic (like the world of the Impressionists). Not much Vermeer jewellery will appear and his bill of fare won't inspire cookbooks. True, the Dutch burghers upheld the honest-to- God family values sure to appeal to a mod- ern American audience, yet Vermeer puts 'View of Delft' c. 1660-1661, Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague an odd spin on them. The more we learn about the artist and the closer we look at his work, the harder it becomes to decide what to make of both.

Of course the easy option is to romanti- cise Vermeer. Even this proves tricky. How to romanticise a man who had 14 children and never once depicted a child, common subjects in Dutch genre painting? He died bankrupt without leaving a rags-to-riches- and-back myth: the people and interiors of these pictures are comfortable while giving no hint of, say, Rembrandt's spendthrift extravagances. Furthermore, the earliest works surprise us in the wrong way — clas- sical and religious subjects such as the sim- pering St Praxedis which may be manna to the eager art historian yet will fail to ignite less specialised souls.

Then suddenly a change occurs. The Brunswick 'Girl with the Wineglass' employs the cast of actors and props found in the scenes by Terboch, de Hooch, Metsu and others. Only Vermeer transforms it all. Keeping the silly goose of a damsel who is chatted up by a dandy, he begins to view the human tale as through the lens of eter- nity. Stage machinery plays no part — no swooping angels or hour-glasses point up a moral, the emblem of Temperance in the window-pane is just that and even the the- atrical gestures count for little. Instead, the ethical sense somehow gravitates to things or, more accurately, rests on the vision that translates them to canvas. Whether in the light scarlet dress or the cloth, jug and fruit on the table, Vermeer's brush seems to cleanse reality for our eyes.

From this point onwards the master- pieces follow thick and fast. Each is differ- ent enough from its neighbour to indicate either that Vermeer — dead at the age of 43 — never repeated himself within a short career, or that scholars still haven't finalised his chronology. One quality com- mon to the works of this middle and great- est phase, nevertheless, is a phenomenal handling of space and light.

To regard the vividness of 'View of Delft', the Queen's 'Music Lesson' and the Metropolitan's 'Young Woman with a Water Pitcher' as realism would be as naive as calling photographs 'realistic'. The instantaneity to these images is the oppo- site of the flux of everyday life. We encounter a clarity here in which time must stop. It is closer to the vividness of things remembered than actually seen. Such radi- ance, calm and order are the stuff of wish- fulfilment.

Vermeer's methods contradict the notion that he merely represented what met his eye. As the catalogue notes, various details in 'The Music Lesson' are illogical and the woman's head is glimpsed at an angle in the mirror while she herself stands ramrod straight. The figure who simultaneously grasps a pitcher and a window frame per- forms no ordinary household act. Delft cannot be approached from the viewpoint that Vermeer chose. What do these goings-on mean? They are especially profound in view of the show's core revelation. Vermeer's genius was to make images so acutely organised in two dimensions as to be virtual patterns that also manage to create the most uncan- ny illusion of volume and depth. His use of the camera obscura, a mechanism that pro- duces a temporary picture by focusing light onto a flat surface, was no doubt one factor here. Still, the temptation exists to discern a personal note in this rendering of a world that suggests another hidden within it. Ver- meer was of Calvinist stock and had con- verted to his wife's Catholicism— this in a Protestant country recovering from horrific occupation by Spain. One wonders if the city in the 'View of Delft' isn't a homely type of New Jerusalem, set not on a hill but at the cusp of a waterway, its little mortals quiet beneath a vast heaven.

Towards the close the ambiguities deep- en. The big 'Allegory of Faith' preaches a sermon that remains hard to stomach, whereas the Louvre's tiny `Lacemaker' has no apparent design on us, though its daz- zling mosaic contains a book and a cushion, elements of devotional prayer. The women in the last works become almost supernatu- ral, apparitions cut from alabaster or agate. Before them, however, come the famous `Girl with a Pearl Earring' and 'Girl in a Red Hat', each awash with light and supremely erotic. We want to find the con- necting thread between these variously car- nal and spiritual visions.

A handful of pictures are not in the exhi- bition and their absence counts, ironically, because of the sheer quality of those that are. Among the missing is 'The Art of Painting' in Vienna. There the artist depicts himself depicting a model, the ker- nel of his own meticulous universe. But even if this implicit self-portrait were on hand, we might be no closer to solving any mysteries. For in 'The Art of Painting' its `The Girl with the Red Hat' c. 1665, National Gallery of Art, Washington creator made a move at once telling and unprecedented. Vermeer's back is turned to our gaze, his face unseen.

Johannes Vermeer continues at the Nation- al Gallery of Art, Washington DC, until 11 February; it opens at the Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague, on 1 March and runs until 2 June.

Previous page

Previous page